'The White House's word means nothing!'

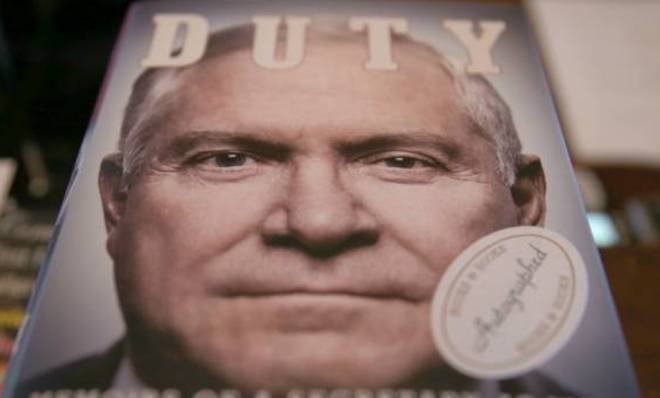

Highlights and nuggets from Robert Gates's Duty: Memoirs of a Secretary Of War

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Former Secretary of Defense Robert Gates does not, in turns out, question President Obama's competence as president of the United States, even as he expressed doubts whether Obama fully believed, or ever believed in, the military's ability to do the jobs Obama assigned to it. That's the key takeaway from my own speed read of his large memoir, which was formally released today. Gates has softened his criticism of Obama in interviews after excepts leaked last week.

Gates has plenty to say about President Obama's foreign policy. Based on a speed read of Duty: Memoirs of a Secretary Of War, here are the highlights you might not have heard about if you've been watching cable news.

Gates almost resigned over White House micro-managing in Libya and its decision to support NATO forces there, something that Gates did not believe to be in the U.S.'s national interests. He blasts White House staff members for making blithe assumptions about military decisions, like how easy it would to be to move an aircraft carrier into the region. (Not nearly as easy as the White House assumed.) Gates said he would often ask, in meetings, "Can I just finish the two wars we're in before you go looking for new ones?" On Libya, Gates lists the following as urging caution: Himself, Vice President Joe Biden, Chief of Staff Bill Daley, National Security Advisor Tom Donilon, deputy NSA advisesr Denis McDonough, and counterterrorism adviser John Brennan. Those in favor: Susan Rice, Ben Rhodes, and Samantha Power.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Gates believes the White House badly mismanaged its response to the uprisings in Egypt, missing the chance to ensure a more orderly transfer of power and sending multiple messages at once. He says that the administration overestimated the effects of Obama's "rhetoric and the effectiveness of public communication" again and again and again and again. And, also, again.

Gen. James "Hoss" Cartwright, the vice chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff who alienated the rests of the chiefs when he was perceived as being too close to the White House, was angling to be either the next chairman or the next national security advisor, and Obama strongly considered placing him in either of those jobs. The straw that broke the Joint Chiefs' back came when Obama asked Cartwright in private for his views on Afghanistan, bypassing the formal chain of command, and sending a signal that he did not trust Admiral Mike Mullen, then the chairman of the Joint Chiefs, to neutrally filter and accurately render Cartwight's advice. Gates regrets not advising Obama to never seek Cartwright's views privately without first consulting Mullen. This breach of protocol, while not appreciable to the outside world, sealed Cartwright's fate. Military opposition to his advancement as chief was solid and growing after that, even though Cartwright's generaliship and personal qualities were not ever in question.

After having been promised that the president would not lobby for additional defense cuts, and after having used his political capital to secure an early round of them, Gates was blindsided in April of 2011 by news that, the very next day, Obama planned to announce another $400 billion cut over ten years. "I pointed my finger at [White House Chief of Staff Bill] Daley and said, 'This White House's word means nothing!'" Daley had promised Gates that the Pentagon would not have to foot the cost for the Libyan operation; a supplemental appropriations request would have taken care of it. But in the end, the Pentagon did eat the costs; Daley had been overruled by the president, who did not want to add money to the war supplemental being prepared for Congress. "You didn't get us a fucking dime," Gates recalls yelling.

Gates mentions that there was a Pakistani nuclear facility a mere six miles from the Abbottabad compound where Osama bin Laden was hiding, a fact that added grave risk to the operation that led to bin Laden's death. Gates also allows that his own over-caution, formed by his experience with such raids, was considered but ultimately (and in Gates's mind, properly) disregarded by the president.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Iraq is once again descending into violence, and the U.S. has almost no presence in the country. It's been said that Obama failed to close on a status of forces agreement with Iraq. Gates says he doesn't know "how hard the Obama administration — or the president personally — pushed the Iraqis for an agreement that would have allowed a residual U.S. troop presence." As he notes, the Iraqi parliament rejected any agreement that allowed for a continued and sustained military footprint in Iraq.

On China, Gates believes that China "has no intention of matching us ship for ship, tank for tank, and missile for missile, and thereby draining [them] financially in a no-holds-barred arms race" against the U.S. Instead, China invests in capabilities that target U.S. vulnerabilities. He writes of an intriguing disconnect between the civilian leaders in China, who did not want to saber rattle and embarrass Gates on his first formal visit to the country, and the People's Liberation Army, which "leaked" footage of a test of the country's new stealth fighter on the eve of the visit. Gates discovered this when he told President Hu that the U.S. press corps was "trying to figuring out the significance of the test in the middle of my visit and just before this trip." How, he wondered, should he respond? Hu "laughed nervously as he turned to his military aides and asked, 'Is this true?' A furious discussion broke out in the Chinese side, involving [two generals] and others. The Chinese civilians in the room had known nothing about the test."

In a White House meeting in March of 2011, Robert Ford, then the U.S. ambassador to Syria, "asserted that Assad is no Qaddafi. There is little likelihood of mass atrocities. The Syrian regime will answer challenges aggressively but will try to minimize the use of lethal force."

Gates notes that "he would be proven horribly wrong."

Marc Ambinder is TheWeek.com's editor-at-large. He is the author, with D.B. Grady, of The Command and Deep State: Inside the Government Secrecy Industry. Marc is also a contributing editor for The Atlantic and GQ. Formerly, he served as White House correspondent for National Journal, chief political consultant for CBS News, and politics editor at The Atlantic. Marc is a 2001 graduate of Harvard. He is married to Michael Park, a corporate strategy consultant, and lives in Los Angeles.

-

Is Andrew’s arrest the end for the monarchy?

Is Andrew’s arrest the end for the monarchy?Today's Big Question The King has distanced the Royal Family from his disgraced brother but a ‘fit of revolutionary disgust’ could still wipe them out

-

Quiz of The Week: 14 – 20 February

Quiz of The Week: 14 – 20 FebruaryQuiz Have you been paying attention to The Week’s news?

-

The Week Unwrapped: Do the Freemasons have too much sway in the police force?

The Week Unwrapped: Do the Freemasons have too much sway in the police force?Podcast Plus, what does the growing popularity of prediction markets mean for the future? And why are UK film and TV workers struggling?

-

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?Talking Point Peter Thiel and Larry Page preparing to change state residency

-

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one report

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one reportIN THE SPOTLIGHT By blocking an approved segment on a controversial prison holding US deportees in El Salvador, the editor-in-chief of CBS News has become the main story

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June

-

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardon

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardonTalking Point Convicted sex trafficker's testimony could shed new light on president's links to Jeffrey Epstein

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred