When politicizing the Olympics is a great idea

President Obama to gay athletes everywhere: It gets better

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

President Obama on Tuesday announced the members of the U.S. delegation to the 2014 Winter Olympic Games in Sochi, Russia — and his choices were an unmistakable shot at the host country and its anti-gay propaganda laws.

Obama tapped tennis legend Billie Jean King and hockey player Caitlin Cahow, both of whom are openly gay. Furthermore, the U.S won't send a president, vice president, or first lady to the Games for the first time since 2000; former Homeland Security Secretary Janet Napolitano will lead the delegation.

It's a brilliant move that sends a pointed signal without escalating the controversy into a full-scale boycott. Obama earlier this year resisted pressure for a boycott, saying that doing so would be counterproductive and hurt most the athletes who wanted to represent their country.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

"One thing I'm really looking forward to is maybe some gay and lesbian athletes bringing home the gold or silver or bronze, which I think would go a long way in rejecting the kind of attitudes were seeing there," Obama said. "And if Russia doesn't have gay or lesbian athletes, it'll probably make their team weaker."

Technically, the Olympic Charter bars all "form[s] of publicity or propaganda, commercial or otherwise," at the Games. But that doesn't mean athletes and nations haven't found ways to politicize the Games before, acts that have left their mark on history.

Beijing, China (2008)

As a presidential candidate in 2008, Obama urged President Bush to boycott China's opening ceremony over the nation's troubling human rights record. Critics were displeased that China had won hosting honors despite concerns about its muffling of free speech, its crackdown on pro-Tibetan demonstrators, and its ties to Sudan.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Many world leaders and human rights groups used the occasion to publicly rebuke China. The demonstrations, as the Washington Post predicted before the Games, would "serve to remind the world not of China's emerging greatness but of its continuing denial of freedom to its citizens, its repression of minorities and its amoral alliances with rogue states."

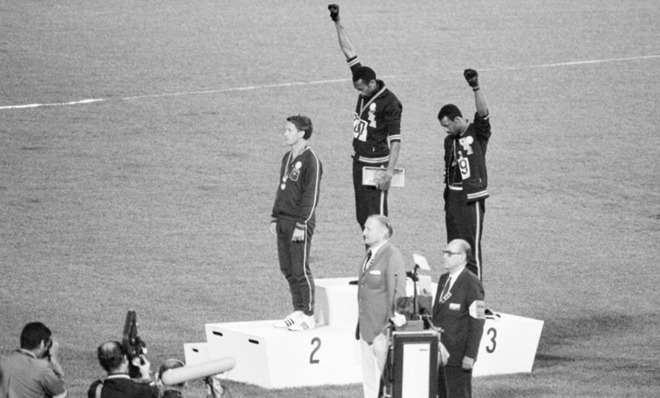

Mexico City, Mexico (1968)

Amid a time of great racial unrest in America — the year saw the assassinations of Martin Luther King, Jr., and Robert F. Kennedy — two black American runners, Tommie Smith and John Carlos, delivered one of the most iconic statements in the history of the Games. As "The Star-Spangled Banner" began to play, the two, draped in medals, raised gloved fists in the black power salute.

The image is indelibly linked to both the Games and America's long, troubling history of racial discrimination that resulted in the Civil Rights movement.

"The first thing I thought was the shackles have been broken," Carlos told the Guardian last year, reflecting on his thoughts at the time. "And they won't ever be able to put shackles on John Carlos again."

Multiple Games (1964-1992)

The International Olympic Committee, in a rare bit of politicization on its own part, banned South Africa from participation for almost three decades because of the nation's apartheid regime. Though South Africa was prevented from competing beginning in 1964, the IOC formalized the ban in 1970 when it voted to expel South Africa's National Olympic Committee.

Apartheid also triggered a last-minute boycott in 1976. That year, some two dozen African nations refused to compete after the IOC permitted New Zealand's rugby squad — which had just played a match in segregated South Africa — to compete in the Games.

With South Africa headed away from apartheid in the early 1990s, the IOC finally lifted the ban.

Berlin, Germany (1936)

Adolf Hitler intended the games to be a proving ground for his theories of Aryan racial superiority. And though his intentions were terrible, his politicization of the Games turned out to be a good thing when it backfired in spectacular fashion.

Jesse Owens, a black American sprinter and long jumper, captured four gold medals in the Games and emerged a hero. The result was a refutation — in Berlin, no less — of Hitler's racist ideals.

Moscow, USSR (1980)

This one is more of a cautionary tale. In 1980, the U.S. led a 65-nation boycott of the Summer Games in Moscow to protest Russia's invasion of Afghanistan.

The boycott in itself wasn't such a bad gesture: Russia had just invaded a foreign country. And though the boycott didn't convince the Soviets to withdraw from Afghanistan, it was at least a strong international rebuke of the military campaign, further isolating the USSR.

Jon Terbush is an associate editor at TheWeek.com covering politics, sports, and other things he finds interesting. He has previously written for Talking Points Memo, Raw Story, and Business Insider.