Doris Lessing, 1919–2013

The plainspoken novelist who rejected the feminist label

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

When Doris Lessing learned she had won the Nobel Prize in literature in 2007 from a gaggle of reporters who congregated at her London home, the author gave a characteristically blunt response. “Oh, Christ,” she said. “I couldn’t care less.” She went on, “I’m 88 years old, and they can’t give the Nobel to someone who’s dead. So I think they were probably thinking they’d better give it to me now before I’ve popped off.”

Doris May Tayler was born in Persia (now Iran) and raised on a farm in the wilds of Southern Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe), said the Financial Times. Her British parents were a “tragic couple”; her father was a troubled World War I amputee, and her mother found rural life in the African bush “emotionally difficult.” Lessing worked on the farm as a child but soon escaped to the capital, Salisbury (now Harare), where she married at the age of 19. Eventually drawn toward communism, she left her husband and their two young children for a leftist German refugee, Gottfried Lessing. “I couldn’t stand that [domestic] life,” she later said. “It’s this business of giving all the time, day and night, trying to conform to something you hate.”

Before long she also became disillusioned with Lessing, said NPR.org. She took Peter, the son from that marriage, to London in 1949 with nothing to her name but a 20-pound note and the manuscript for her first novel, The Grass Is Singing. The novel was a modest success, but it was The Golden Notebook that made her name, in 1962. The book chronicles a single mother’s political, social, sexual, and emotional awakening in postwar London and was widely hailed as breaking the conventions of the traditional novel. It was soon considered a feminist classic, even though Lessing rejected the characterization. “Oh, it’s just stupid; I’ve seen it so often,” she said. “There’s nothing feminist about The Golden Notebook.” The book, she insisted, was mainly about the collapse of communism.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Lessing’s work drifted from realism into science fiction in the 1960s and ’70s, said The Daily Telegraph (U.K.). The Four-Gated City imagines a global plague sparking World War III; The Memoirs of a Survivor features a heroine who can travel through space and time. Lessing dabbled in new beliefs, from the psychoanalytic doctrine of R.D. Laing to Islamic Sufism. She became increasingly cynical about the publishing industry, writing two poorly reviewed novels under a pseudonym to deliberately expose the literary world’s failure to recognize good writing. Both were rejected by her own publisher, a fact that “gave her a great deal of pleasure.”

In later life Lessing “reveled in her status as a contrarian,” said the Los Angeles Times. She visited Pakistan in 1986 to back the cause of the Afghan mujahedeen, but was vocally critical of their treatment of women. Time and again she broke with the feminist movement, criticizing its emphasis on white, middle-class women and sensitivity to what she saw as nonissues like sexual harassment. She was heavily criticized for downplaying the September 11, 2001, attacks as “not that terrible” compared with the Irish Republican Army’s multiyear terror campaign in Ireland and the U.K. “I tend to speak my mind, which is not necessarily a good idea,” she once said. “I do not think I am the soul of tact.”

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

-

The mystery of flight MH370

The mystery of flight MH370The Explainer In 2014, the passenger plane vanished without trace. Twelve years on, a new operation is under way to find the wreckage of the doomed airliner

-

5 royally funny cartoons about the former prince Andrew’s arrest

5 royally funny cartoons about the former prince Andrew’s arrestCartoons Artists take on falling from grace, kingly manners, and more

-

The identical twins derailing a French murder trial

The identical twins derailing a French murder trialUnder The Radar Police are unable to tell which suspect’s DNA is on the weapon

-

James Van Der Beek obituary: fresh-faced Dawson’s Creek star

James Van Der Beek obituary: fresh-faced Dawson’s Creek starIn The Spotlight Van Der Beek fronted one of the most successful teen dramas of the 90s – but his Dawson fame proved a double-edged sword

-

Catherine O'Hara: The madcap actress who sparkled on ‘SCTV’ and ‘Schitt’s Creek’

Catherine O'Hara: The madcap actress who sparkled on ‘SCTV’ and ‘Schitt’s Creek’Feature O'Hara cracked up audiences for more than 50 years

-

Bob Weir: The Grateful Dead guitarist who kept the hippie flame

Bob Weir: The Grateful Dead guitarist who kept the hippie flameFeature The fan favorite died at 78

-

Brigitte Bardot: the bombshell who embodied the new France

Brigitte Bardot: the bombshell who embodied the new FranceFeature The actress retired from cinema at 39, and later become known for animal rights activism and anti-Muslim bigotry

-

Frank Gehry: the architect who made buildings flow like water

Frank Gehry: the architect who made buildings flow like waterFeature The revered building master died at the age of 96

-

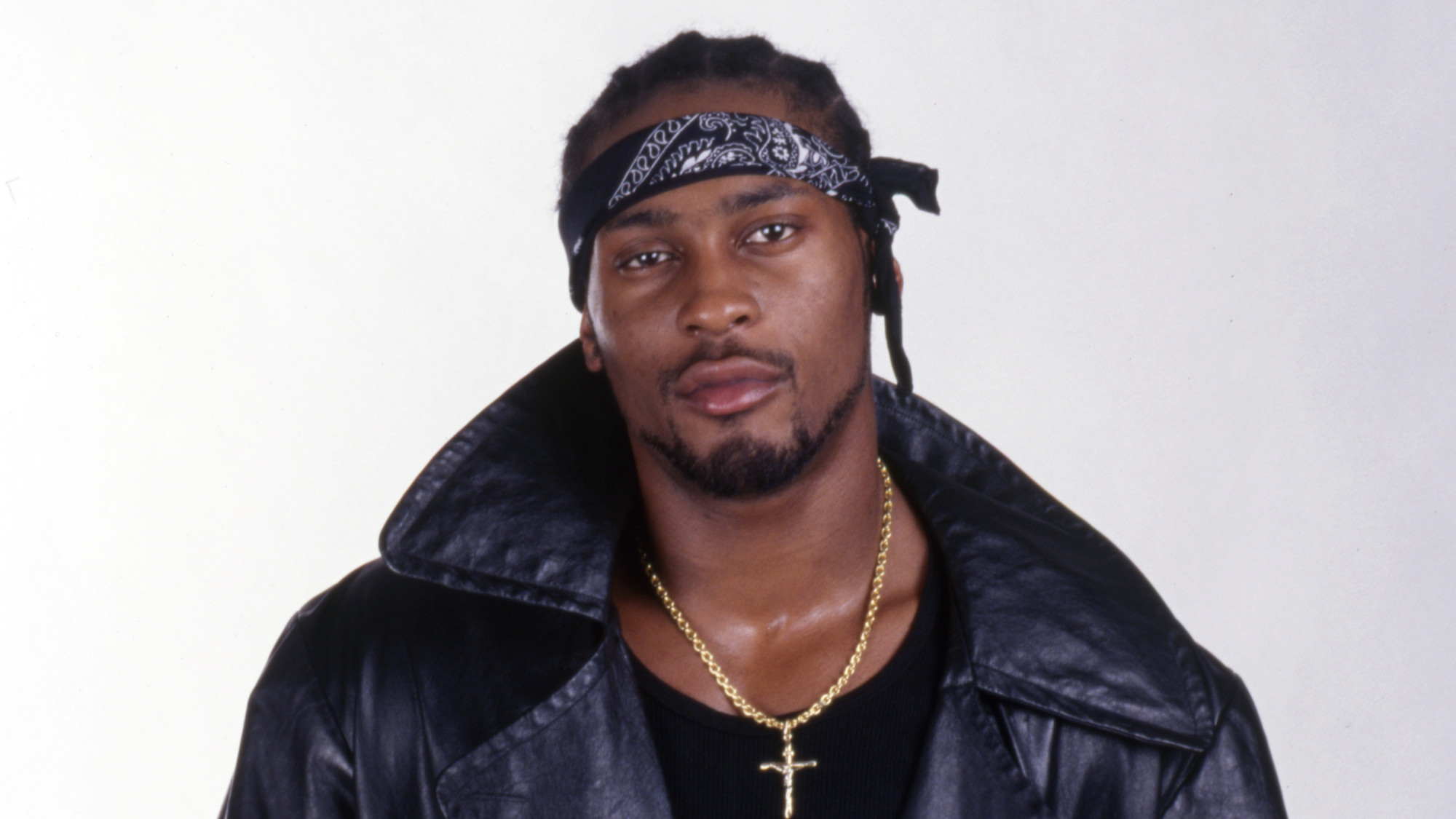

R&B singer D’Angelo

R&B singer D’AngeloFeature A reclusive visionary who transformed the genre

-

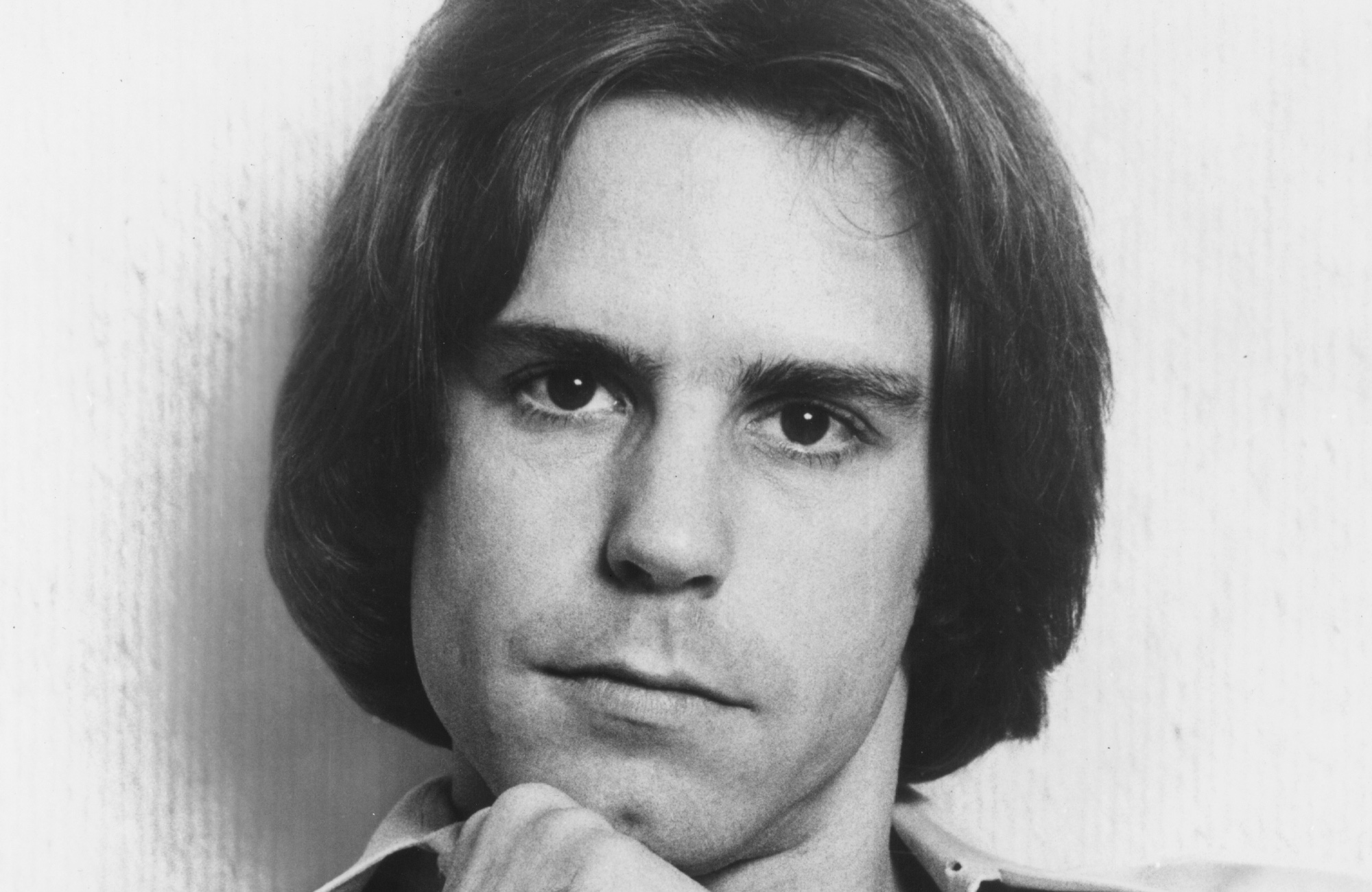

Kiss guitarist Ace Frehley

Kiss guitarist Ace FrehleyFeature The rocker who shot fireworks from his guitar

-

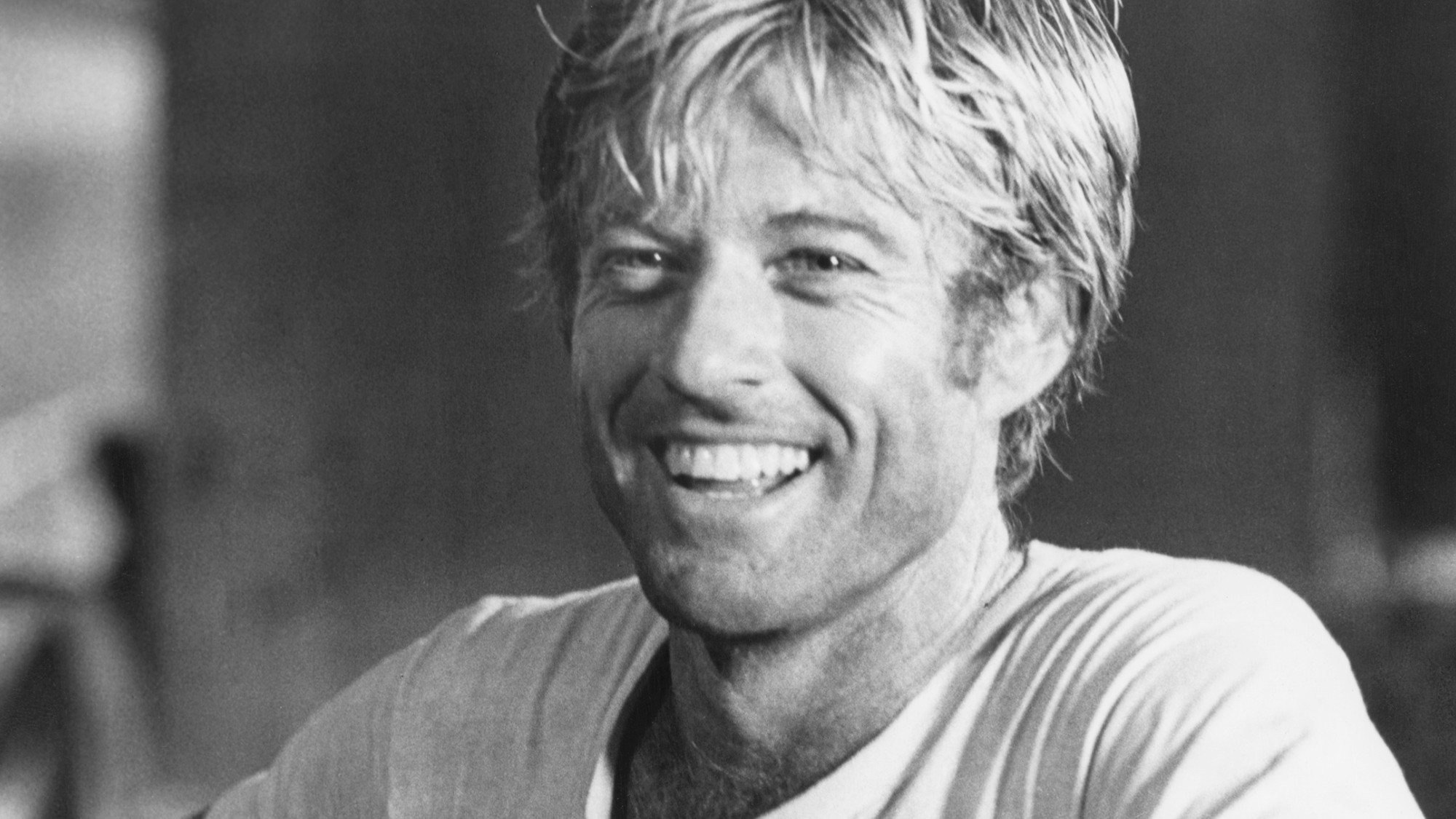

Robert Redford: the Hollywood icon who founded the Sundance Film Festival

Robert Redford: the Hollywood icon who founded the Sundance Film FestivalFeature Redford’s most lasting influence may have been as the man who ‘invigorated American independent cinema’ through Sundance