Qatar: The tiny nation that roared

Qatar has used its petro-riches to buy global clout. What does the emirate actually want?

How rich is Qatar?

The 250,000 native Qataris are the world's richest people, with an average annual income of about $400,000. That's because the tiny Arab nation, a Connecticut-size peninsula jutting out from Saudi Arabia into the Persian Gulf, sits on the world's third-largest natural-gas reserves. That resource has enabled pint-size Qatar (pronounced KUH-tr, not ka-TAR) to employ 92 percent of its citizens in government-funded jobs, and to fund an outsize role in the world. Since 2011, the emirate has spent at least $17 billion supporting Arab Spring revolts and bankrolling Islamist groups across the Middle East. In Europe, the ruling Al Thani family has snapped up skyscrapers, soccer clubs, and banks. In the U.S., the country has given generously to the Brookings Institution, an influential think tank, including $2.5 million in 2012. Last month, the emirate launched Al Jazeera America, an offshoot of Qatar's international news network. "Qatar wants to be the [Arab world's] next superpower," said Fawaz Gerges, a Middle East expert at the London School of Economics.

Has Qatar always been a global player?

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

For most of its history, the emirate was an impoverished back-water, home to a few thousand pearl fishermen and nomadic tribesmen. The discovery of oil and gas in 1940 made locals rich, but it wasn't until 1995, when Hamad bin Khalifah Al Thani deposed his father, Sheik Khalifa, in a bloodless coup, that Qatar became a force in the region and beyond. While the old sheik avoided getting involved in international affairs out of fear of angering his larger, more powerful neighbors, Iraq's 1990 invasion of Kuwait — another small, hydrocarbon-rich state — taught Hamad that keeping a low profile could be dangerous. "If you are going to be invaded," said David Roberts, a director at Britain's Royal United Services Institute, "you don't want people to go, 'Qatar? There's a country that begins with a Q? Where's that?'"

How did he raise Qatar's profile?

First, he let the U.S. set up its regional military headquarters just outside the capital, Doha. Hamad then went about stitching Qatar tightly into the global economy. He built the world's largest facilities for condensing liquid natural gas, which the emirate now exports to Europe, Japan, and India. In 1996, Hamad launched Al Jazeera — a 24-hour news station that combined aggressive reporting, high production values, and an Islamic worldview. "It really projected Qatar to a role of importance in the region," said William Youmans, a media expert at George Washington University. Qatar now hopes Al Jazeera America will raise the emirate's reputation in the U.S. "It's really about enhancing Qatar's visibility, prestige, and influence," said Youmans. Others, however, fear the channel will push hateful propaganda on American audiences.

What kind of propaganda?

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

The conservative media-watchdog group Accuracy in Media says that the station's Arabic parent has given considerable airtime to extremists such as Yusuf al-Qaradawi, a Muslim cleric who has praised the killing of U.S. troops in Iraq. The group also points out Qatar's history of backing radical Islamists. The emirate gave $8 billion to Egypt's Muslim Brotherhood–led government, funnels cash and weapons to Islamist fighters in Syria, and last year handed $400 million to Hamas, the hard-line Palestinian organization. But executives at Al Jazeera America — which employs some 800 journalists and staff in the U.S., most of them Americans — insist their programming is "editorially independent" of Doha. So far, the channel has focused on such topics as the hunger strike in California prisons and the impact of Chicago school closures, making Al Jazeera America look more like "NPR with pictures" than "terror TV," said Lawrence Pintak, a media analyst at Washington State University.

Does Qatar support radical Islam?

Qatar is actually a relatively moderate Islamic state. Unlike in neighboring Saudi Arabia, women are allowed to drive, non-Muslims can buy alcohol, and young men and women often hold hands in public. Many Middle East experts say Qatar's rulers are pragmatists, not ideologues, and are trying to walk a very fine line between having influence in the West and cultivating favor in the Islamic world. When the Arab Spring broke out, said international relations professor Gregory Gause of the University of Vermont, Qatar's rulers "made a decision: 'If we are going to play, we are going to be with the people on the rise and that is the Islamists.'"

Has betting on Islamists paid off?

It's backfiring. Egypt's new military rulers recently accused Al Jazeera of supporting terrorism by airing interviews with Brotherhood supporters, and shut down its offices in Cairo and began jamming its signals. The emirate's support for Islamist militias has also angered Libya's interim government. When Sheik Hamad stepped down this summer in favor of his son, Tamim, the new emir called for an end to "arrogant" policies — an indication he might scale back his father's attempts to exert influence abroad. "For years, Qatar has been punching above its weight," said Simon Henderson, a Middle East expert at the Washington Institute. "Now, some may just try punching back."

Qatar's weighty problem

The emirate isn't just the world's richest country, it's also one of the fattest. Half of adults and a third of children are obese, and almost 17 percent of the native population suffers from diabetes. By comparison, about a third of Americans are obese, and 8 percent diabetic. The problem is that Qataris are so rich that they don't need to work, and have developed a taste for fatty American fast food. "In Qatar, we just sit, smoke, and eat junk food," one resident told The Atlantic. "Everything is done for us." The government has tried to battle the bloat by encouraging Qataris to eat less and exercise more. But the country's traditional culture makes it difficult for anyone to go on a diet. "If you don't eat, it's considered a shame," one Qatari told The New York Times, "and if you leave someone's home without eating it's a shame."

Theunis Bates is a senior editor at The Week's print edition. He has previously worked for Time, Fast Company, AOL News and Playboy.

-

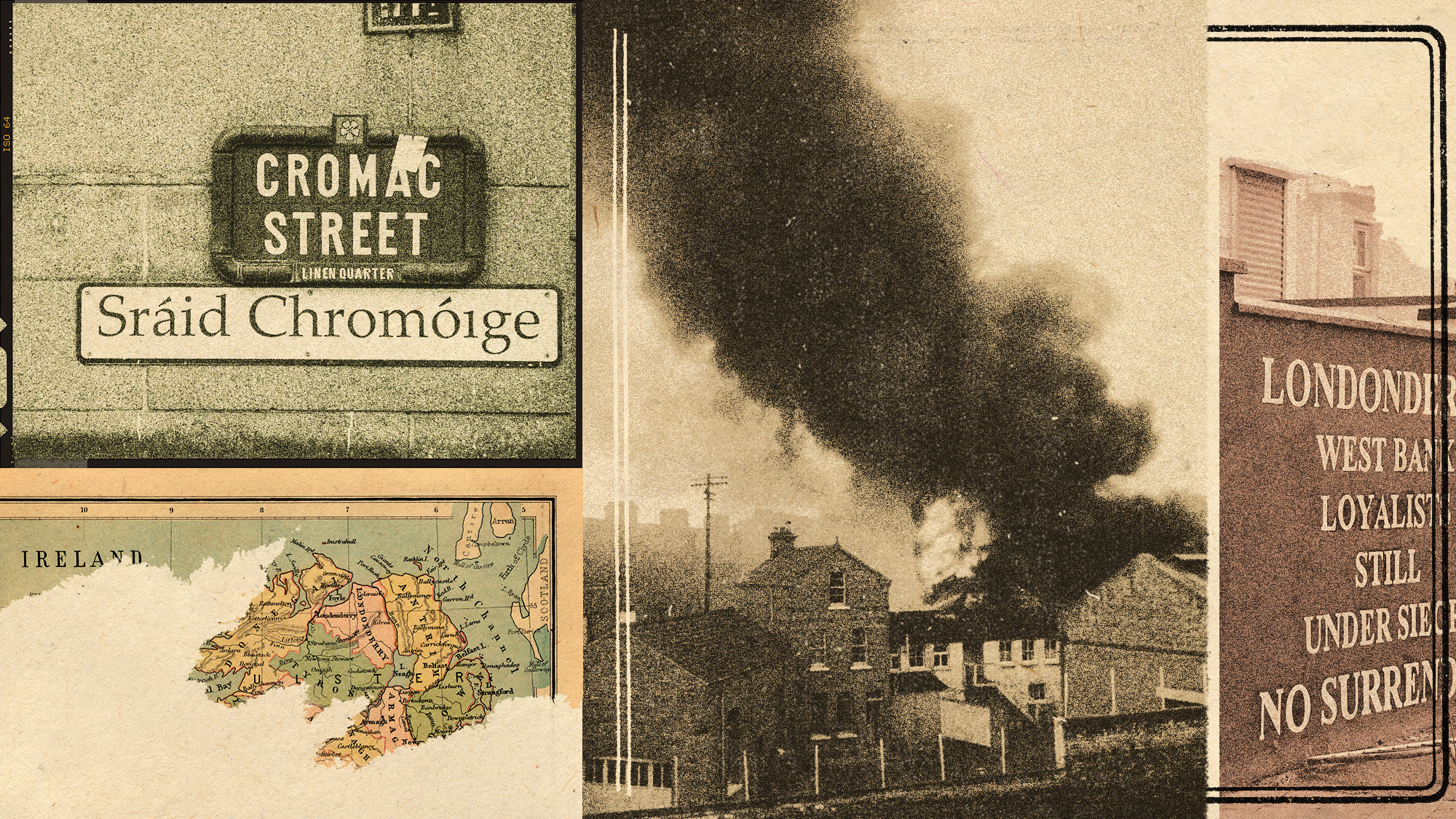

The battle over the Irish language in Northern Ireland

The battle over the Irish language in Northern IrelandUnder the Radar Popularity is soaring across Northern Ireland, but dual-language sign policies agitate division as unionists accuse nationalists of cultural erosion

-

Villa Treville Positano: a glamorous sanctuary on the Amalfi Coast

Villa Treville Positano: a glamorous sanctuary on the Amalfi CoastThe Week Recommends Franco Zeffirelli’s former private estate is now one of Italy’s most exclusive hotels

-

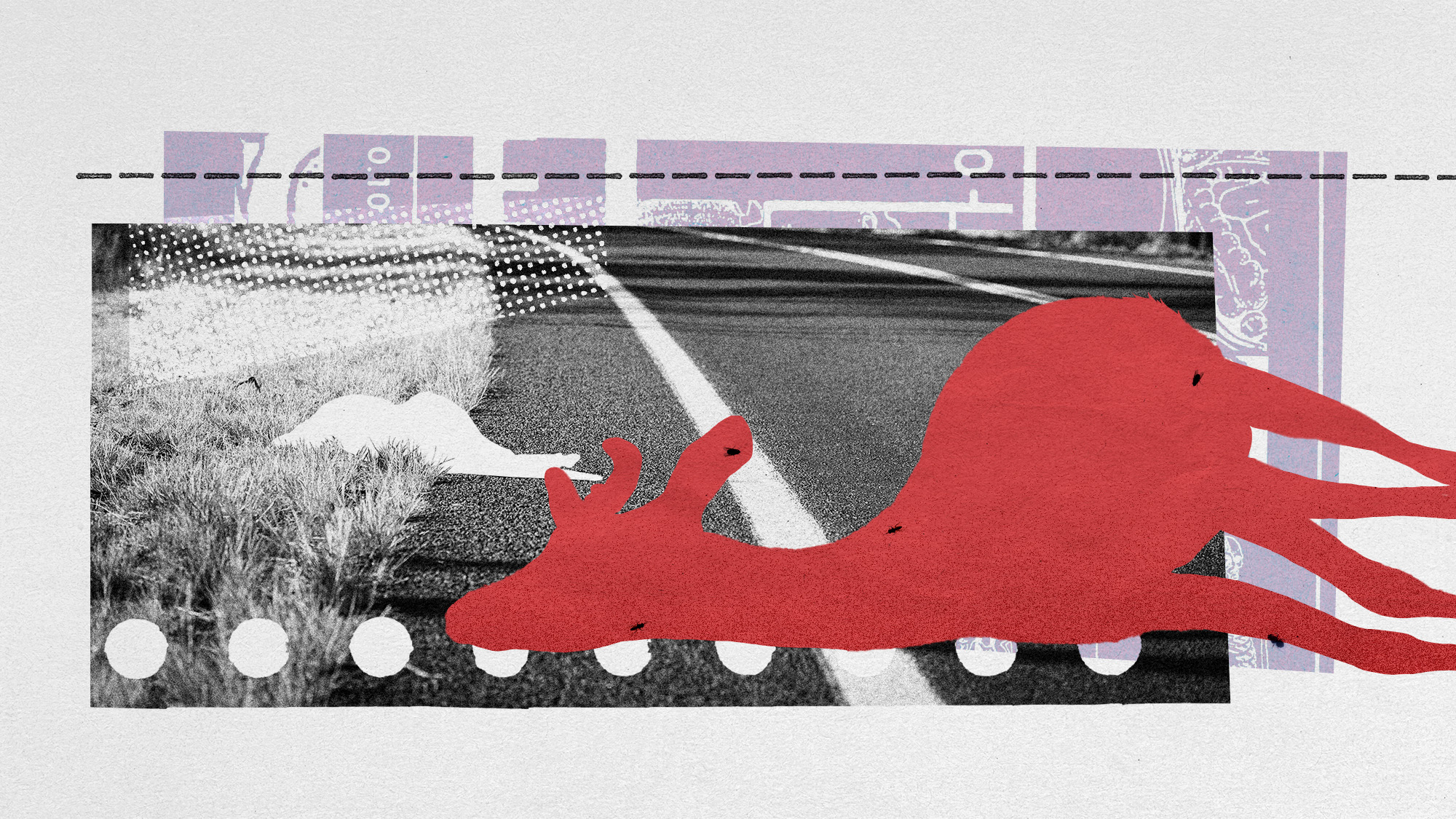

How roadkill is a surprising boon to scientific research

How roadkill is a surprising boon to scientific researchUnder the radar We can learn from animals without trapping and capturing them