Why scandal politics don't work

Perhaps the GOP should focus on more effective political strategies...

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

A president's critics can't help themselves when the whiff of scandal is in the air. Yet more often than not, the obsessive pursuit of scandal fails to lift the political prospects of the opposition party.

Republicans might want to pause and ask themselves: Is flogging Benghazi, the IRS, and the Associated Press really the best way to get the majority back?

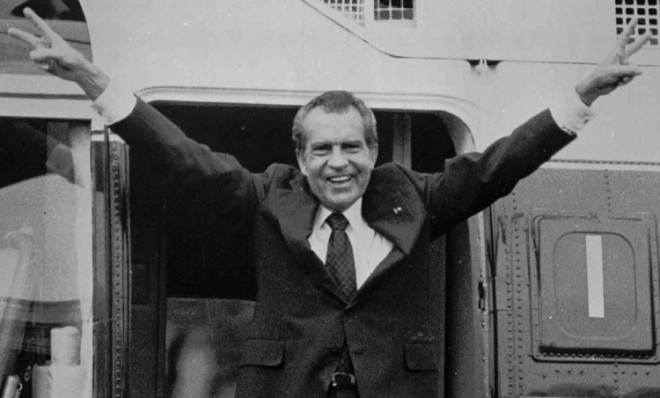

Every party on the outside of the White House envisions replicating Watergate — forcing a president out of office and riding the aftermath to an Election Day triumph. But the post-Watergate scandal-mongering record falls far short of that holy political grail.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

The Iran-Contra affair may be a blot on the Reagan record, but it didn't propel Democratic Gov. Michael Dukakis into the White House. During his convention speech, he tried to tar then-Vice-President George H. W. Bush for "sit[ting] silently by when somebody at the National Security Council comes up with the cockamamie idea that we should trade arms to the Ayatollah for hostages." A few days later, Dukakis also tried to make hay with a less-remembered scandal involving fraudulent procurement in the Pentagon. "A fish rots from the head first," said Dukakis, in some of his harshest words of the campaign. His emphasis on ethics were soon drowned out with a barrage of attacks regarding his views on national security and crime.

Ten years later, with Bill Clinton in the Oval Office, Republicans took scandal-mongering to new heights. Charging the president with perjury and obstruction of justice to cover up his extramarital affair, the House Judiciary Committee advanced articles of impeachment one month before the 1998 congressional midterm elections. The opposition party historically gains seats at the "six-year itch" point of a president's tenure. But the backlash from the impeachment obsession allowed Democrats to pick up five House seats. Speaker Newt Gingrich was compelled to quit Congress. House Republicans barreled ahead and formally impeached Clinton anyway. Clinton's approval rating then spiked above 70 percent.

During George W. Bush's first term, Democrats sought to drive outrage surrounding the Abu Gharib torture scandal and, to a lesser extent, the outing of undercover CIA agent Valerie Plame. Michael Moore sought to spark a scandal with his documentary Fahrenheit 9/11, which characterized Bush's foreign policy and energy policy as flowing from a scandalous relationship with Saudi Arabia. John Kerry's acceptance speech, delivered one month after the movie was released, called for "an America that relies on its ingenuity and innovation, not the Saudi royal family." A well-financed independent group, The Media Fund, aired a series of ads criticizing Bush's Saudi ties. Bush ended up winning the popular vote (unlike 2000).

As for President Obama — the conservative cries of "Solyndra" and "Fast and Furious" failed to interrupt his march to a second term.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Why do scandal politics usually fail? Of course, some scandals fizzle out because the charges lack merit or import. But as you see above,

even more significant scandals can lack political punch. Perhaps that is because by attempting to quickly topple the president and short-cut a path the White House, the attackers end up distracting themselves from their own primary mission: discrediting the president’s ideology and substantive agenda in the eyes of the public, and elevating their own.

A more plausible objective, short of impeachment or electoral gains, would be to consume a White House with scandal management and distract the administration from executing the president's agenda. But for today's Republicans, that objective doesn't make much sense. Obama's main legislative goal this year is shared by leading Republicans: immigration reform.

In fact, pro-immigration Republicans may be stoking the fires about Benghazi, the IRS and the AP not to distract the president, but to distract fellow conservatives who otherwise would rally the Tea Party base to pressure Congress and undermine the bipartisan Senate bill. As the Daily Caller's Mickey Kaus told BuzzFeed: "I think these distracting scandals actually help its chances of passing. Every time [the bill] is at center stage, its chances of passing go down."

And note that some of Obama's chief antagonists on Benghazi — Sens. John McCain and Lindsey Graham — are also Obama's key shepherds of immigration reform.

For those conservatives more deeply opposed to President Obama's agenda, they should ask themselves: Do we really think any of these "scandals" seriously threaten President Obama's hold on the Oval Office? And if they don't, might there be a better use of our time?

Bill Scher is the executive editor of LiberalOasis.com and the online campaign manager at Campaign for America's Future. He is the author of Wait! Don't Move To Canada!: A Stay-and-Fight Strategy to Win Back America, a regular contributor to Bloggingheads.tv and host of the LiberalOasis Radio Show weekly podcast.

-

Should the EU and UK join Trump’s board of peace?

Should the EU and UK join Trump’s board of peace?Today's Big Question After rushing to praise the initiative European leaders are now alarmed

-

Antonia Romeo and Whitehall’s women problem

Antonia Romeo and Whitehall’s women problemThe Explainer Before her appointment as cabinet secretary, commentators said hostile briefings and vetting concerns were evidence of ‘sexist, misogynistic culture’ in No. 10

-

Local elections 2026: where are they and who is expected to win?

Local elections 2026: where are they and who is expected to win?The Explainer Labour is braced for heavy losses and U-turn on postponing some council elections hasn’t helped the party’s prospects

-

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?Talking Point Peter Thiel and Larry Page preparing to change state residency

-

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one report

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one reportIN THE SPOTLIGHT By blocking an approved segment on a controversial prison holding US deportees in El Salvador, the editor-in-chief of CBS News has become the main story

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June

-

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardon

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardonTalking Point Convicted sex trafficker's testimony could shed new light on president's links to Jeffrey Epstein

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred