Terrence Malick's moving Christian message — and film critics' failure to engage with it

The divisive director's last two films were essentially ecstatic cinematic tributes to God. But you wouldn't know it from reading the reviews

Christianity gets a lot of bad press, much of it richly deserved. Evangelical Protestants have been making a decisive contribution to anti-intellectualism in American life for a long time now, and today they continue to produce more than their share of creationist claptrap and sentimentalist kitsch. Catholics, for their part, often do little better, with leading clerics and lay intellectuals fixated on policing sexual morals and seemingly eager to treat the church as a wholly owned subsidiary of the Republican Party.

Obviously, there is so much more to Christianity than this. And the recent work of filmmaker Terrence Malick shows us exactly what that is.

Both The Tree of Life (2011) and the just-released To the Wonder are deeply Christian in outlook and inspiration — and both demonstrate the religion's continued power to serve as a vital cultural and intellectual force.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Mainstream critics hardly seem to have noticed. The problem isn't that reviews of the films have been negative. (Many critics praised The Tree of Life, while To the Wonder has been widely panned.) The problem is that, regardless of whether they've admired or ridiculed the films, the vast majority of mainstream critics have failed to treat them as the profoundly religious — and specifically Christian — works of art that they are. Whether or not the silence is a product of the theological illiteracy and scriptural ignorance that typically prevails among overwhelmingly secular journalists, something essential about these remarkable films has been missed.

(Beware: Spoilers lie ahead.)

Critics did a passable job with The Tree of Life. In part that was because its religious themes and cosmic ambitions were impossible to miss. Here was a movie that asked sweeping theological questions — What is the meaning of suffering and loss? Why does God permit it? What kind of consolation can faith provide? — and answered them on the broadest possible terms. The film begins with one man's anguished efforts to come to terms with the death of his brother. From there it returns to the creation of the universe, gives us a glimpse of the origins of divine grace among the dinosaurs, explores the man's boyhood struggles with his father, mother, and ill-fated brother, and finally portrays the end of life on earth and a reconciliation of loved ones in heaven. Many critics found it impossible not to be swept away by the audacity of Malick's cinematic vision and breathtaking ambition.

Yet even the most positive reviews of The Tree of Life skated over its numerous theological and scriptural allusions, and several critics who otherwise praised the film openly mocked the Fellini-esque vision of the afterlife with which it concludes. (One wonders if these critics also roll their eyes at the biblical verse in which we are promised that in heaven God will wipe away every tear from our eyes.)

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

To the Wonder has fared far worse. On the most obvious level, the movie tells a straightforwardly tragic love story: An American man (Neil, played by Ben Affleck) and French woman (Marina, played by Olga Kurylenko) fall for each other in Paris; they hit the skids after she returns with him to Oklahoma; Neil takes up with a second woman (Jane, played by Rachel McAdams); that relationship also fails; Neil and Marina give it another go; when things deteriorate further, they go their separate ways. The End. If that's all there were to it — an unimaginative plot presented in Malick's sumptuous visual style and acted by largely mute characters who speak mainly in elliptical voiceovers — To the Wonder would be the beautiful but boring failure so many critics are saying it is.

But that's not all there is to it. On a deeper level, the film is Malick's meditation on the Christian vision of love — and the obstacles that we perversely place in the way of satisfying our irrepressible longing for it. Anyone who's fallen in love is familiar with the feeling: The world appears transfigured. In the first words of the film, Marina describes it as being "newborn," called "out of the shadows." In a series of quick scenes filmed in Paris, the lovers touch and embrace each other bathed in radiant sunlight. In voiceover, Neil calls Marina "my sweet love... my hope." Marina says their love unites them, makes one person out of two.

Ultimately, for Malick, the experience of falling in love grants us a glimpse of the divine — of a "Love that loves us" (as Marina twice describes it in voiceover, once at the beginning and again at the end of film). Early in the movie, Neil and Marina feel their love intertwine with the sacred when they pay a visit to the stunning church on the island of Mont Saint-Michel off the northwest coast of France, where the lovers (in Marina's words) "climbed the steps to the wonder." (The island and church, nicknamed "the wonder" [le merveille], gives the film its title.)

But love is not only rapture. In Malick's Christian view, it also calls on us to sacrifice, to give ourselves over fully to the one we love. Once Marina moves to Oklahoma with Neil, a new character (a priest named Father Quintana, movingly played by Javier Bardem) expresses these sentiments in voiceovers and homilies from the pulpit of his church. Paraphrasing Ephesians 5:25, Father Quintana declares that "a husband is to love his wife as Christ loved the church and give his life for her." It is in undertaking this sacrifice that we participate in "the divine presence, which sleeps in each man, in each woman."

Marina is eager for such sacrifice, but Neil resists it, with Marina but also with Jane — both of whom long to have children with him. (Children haunt the film, promising a happiness and fulfillment, and demanding a commitment, that is never chosen.) Glancing longingly at other women, Neil prefers to remain aloof, forever keeping his options open, turning love (in Jane's words) into "nothing: pleasure, lust," instead of treating it as the divine "command" that Father Quintana says it is: "Love is not only a feeling. Love is a duty. You shall love... You feel your love has died? It is perhaps waiting to be transformed into something higher."

Not that Father Quintana is some kind of saint. On the contrary, like Neil, he struggles with love — in his case, the priestly call to brotherly love or charity (agape). Lonely and lost, he says he "thirsts" for God but worries that the "stream is dried up." In voiceover, he confesses to God: "Everywhere you are present. And still I can't see you. You're within me. Around me. And I have no experience of you. Not as I once did. Why don't I hold onto what I've found? My heart is cold. Hard."

That so many reviewers have either ignored Father Quintana's role in the film, or seen his struggles as an uninteresting subplot unrelated to the movie's exploration of romantic and sexual love, is perhaps the most stunning critical oversight of all. Just as Neil holds himself back, refusing to give in to all that love demands, Father Quintana often fails to detect the presence of God all around him and sometimes withholds himself from the most troubled and troubling people to whom he's called to minister (including prisoners and drug addicts).

Yet unlike Neil, who ends up alone, Father Quintana achieves a spiritual epiphany during a sequence toward the end of the movie that is unlike any I have ever encountered in film, and one I have not seen referenced in a single mainstream review. As the priest comforts a succession of suffering people — the old, the anguished, the crippled, the sick, and the dying — he recites a devotion of St. Patrick: "Christ be with me. Christ before me. Christ behind me. Christ in me. Christ beneath me. Christ above me. Christ on my right. Christ on my left. Christ in the heart." The sequence reaches its climax with the recitation of a prayer by Cardinal Newman (one that was also prayed daily by Mother Teresa's Sisters of the Missionaries of Charity): "Flood our souls with your spirit and life so completely that our lives may only be a reflection of yours. Shine through us. Show us how to seek you. We were made to see you."

Humanity was made for God. And he is present all around us — in the transfiguring, wondrous joy of romantic love, in self-giving sacrifice, in our suffering and the suffering of others, in the charity we offer to those in pain, in the resplendent beauty of the natural world — if only we open our eyes to see him. That, it seems, is Terrence Malick's scandalous message.

Take it or leave it. Be moved by it or dismiss it as mystical nonsense. But please, recognize it for what it is: an ecstatic cinematic tribute to God.

Damon Linker is a senior correspondent at TheWeek.com. He is also a former contributing editor at The New Republic and the author of The Theocons and The Religious Test.

-

The best dark romance books to gingerly embrace right now

The best dark romance books to gingerly embrace right nowThe Week Recommends Steamy romances with a dark twist are gaining popularity with readers

-

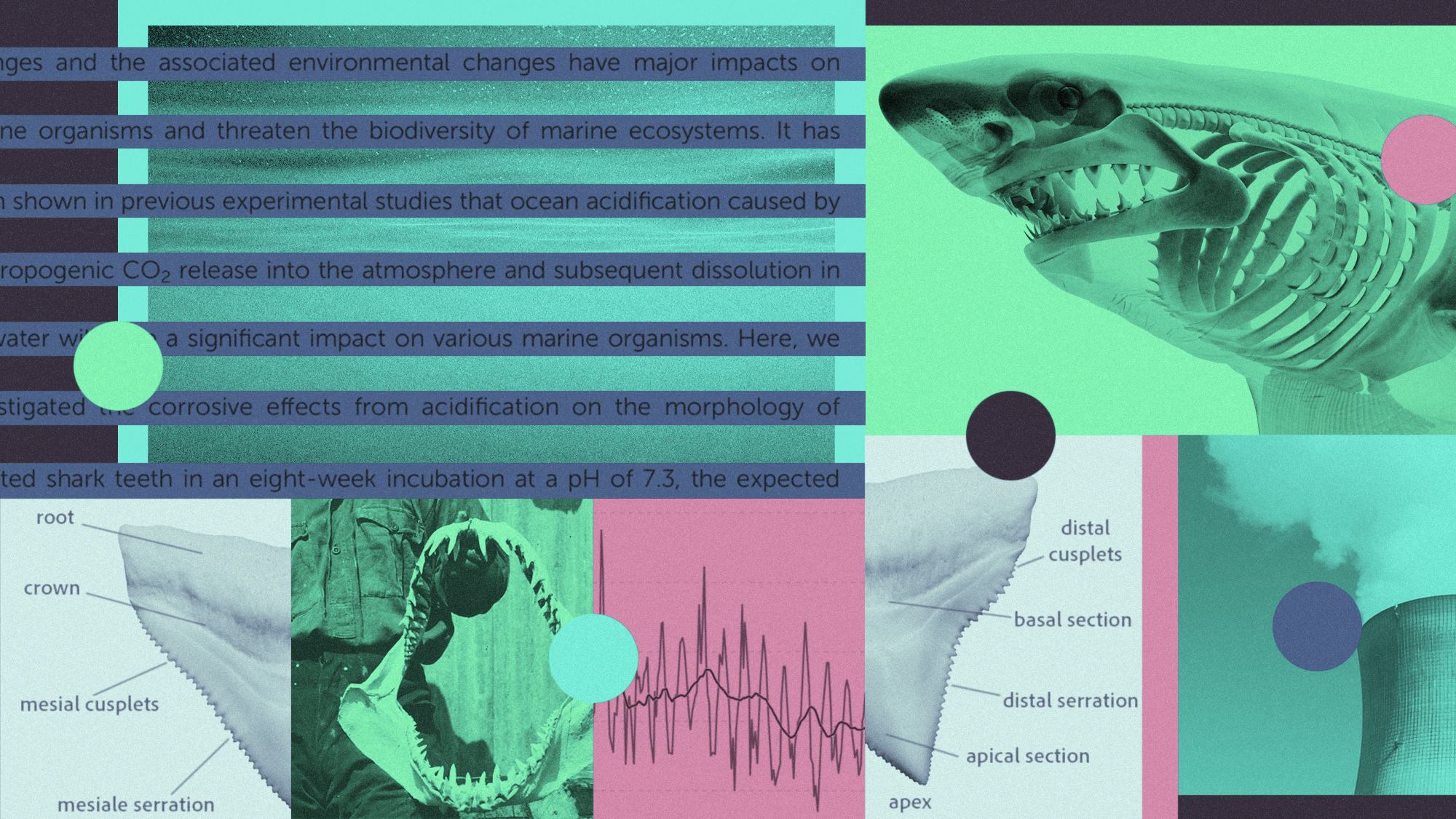

The ocean is getting more acidic — and harming sharks’ teeth

The ocean is getting more acidic — and harming sharks’ teethUnder the Radar ‘There is a corrosion effect on sharks’ teeth,’ a study’s author said

-

6 exquisite homes for skiers

6 exquisite homes for skiersFeature Featuring a Scandinavian-style retreat in Southern California and a Utah abode with a designated ski room