5 smart reads for the weekend

An exploration of failed apocalypse forecasters. A profile of presumptive secretary of state nominee John Kerry. And more compelling, of-the-moment stories to dive into

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

1. "A year after the non-apocalypse: Where are they now?"

Tom Bartlett, Religious Dispatches Magazine

If you’re reading this article, the Mayan apocalypse — which was allegedly scheduled to occur on Friday, December 21 — didn’t happen. The news will undoubtedly come as a mild relief to the vast majority of the human race, but for those who genuinely believed and took pains to prepare themselves for the end of the world, surprise and disappointment are the prevailing emotions. How do you go on living after bracing yourself for the apocalypse? Here's an excerpt from an interview with the followers of Harold Camping, who had predicted that the world would end on May 21, 2011, one year after their apocalypse failed to occur:

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

I was struck by how some believers edited the past in order to avoid acknowledging that they had been mistaken. The engineer in his mid-twenties, the one who told me this was a prophecy rather than a prediction, maintained that he had never claimed to be certain about May 21. When I read him the transcript of our previous interview, he seemed genuinely surprised that those words had come out of his mouth. It was as if we were discussing a dream he couldn’t quite remember. Other believers had no trouble recalling what they now viewed as an enormous embarrassment.... In the beginning, I was curious how believers would react, as if they were mice in a maze. But as time went on I grew to like and sympathize with many of them. This failed prophecy caused real harm, financially and emotionally. What was a curiosity for the rest of us was, for them, traumatic. And it’s important to remember that mainstream Christians also believe that God’s son will play a return engagement, beam up his bona fide followers, and leave the wretched remainder to suffer unspeakable torment. They’re just not sure when.

Read the rest of the story at Religious Dispatches Magazine.

2. "John Kerry: Candidate in the making"

Michael Kranish, The Boston Globe

On Friday, senior White House officials confirmed that President Barack Obama would nominate Sen. John Kerry (D) to take Hillary Clinton’s place as the next secretary of state. The position would be the latest step in a decades-long political career for Kerry, who rose to national prominence when he challenged incumbent George W. Bush for the presidency in 2004. In a seven-part series written in advance of Kerry’s failed presidential campaign, the staff of The Boston Globe took an in-depth look at John Kerry’s life and career:

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

The rap on John Kerry is that he is an aloof politician who lacks a core. Part of his personal story feeds the image: Kerry is a man without geographic roots; his youth stretched through a dozen towns across two continents. He enjoyed the cachet of illustrious family names but not always the bonds of a household. By the time he was 10 years old, he was shipped off for an eight-year odyssey at boarding schools in Switzerland and New England, where "home'' was a dormitory or an aunt's estate. More than any one place, his ties were to a social milieu — that rarefied world of wealth and privilege where the French is fluent and the manners impeccable. As a young man, Bill Clinton got a chance to shake JFK's hand on a Boys Nation outing; young John Kerry dated Jacqueline Kennedy's half-sister and once sailed Narragansett Bay with JFK at the helm. But Kerry did not fully belong to this elite world, either. His father's government salary, combined with his own struggles with money, left him planted further on the outskirts of New England's ruling class than many realized. The boy who was educated at patrician prep schools grew into a gentleman without significant means, part of a landless aristocracy that one might find in a Jane Austen novel. He married wealthy wives whose net worth dwarfed his own.

Read the rest of the story at The Boston Globe.

3. "What to do about the first amendment"

Robert Bork, Commentary Magazine

On Wednesday, legal scholar and former Supreme Court nominee Robert Bork died of complications from heart disease at age 85. Bork leaves behind a complicated legacy that remains a source of dispute between Democrats, who successfully voted down Bork’s nomination to the Supreme Court amid concerns over his strict originalist philosophy, and Republicans, who contend that Bork was the victim of unfair and inaccurate attacks. Judge for yourself whether Bork would have made an effective Supreme Court Justice with this article he wrote about the first amendment in 1995:

The text of the First Amendment is quite simple: Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press, or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the government for a redress of grievances." These are not words that would lead the uninitiated to suspect that the law, both with regard to religion and with regard to speech, could be what the Supreme Court has made of it in the past few decades... At this moment, the most prominent issue involving the religion clauses of the First Amendment stems from the decision in Engel v. Vitale (1962), and subsequent cases, prohibiting prayer, Bible reading, or even a moment of silence in public schools. In addition to declaring that these are all violations of the First Amendment, the Court has held unconstitutional even school practices that are neutral as among different religions on the ground that, under the First Amendment, religion may not be preferred to irreligion. Since the vast majority of Americans are believers, these holdings are fiercely resented by most of them as attempts to impose secularism on their children, and school prayer remains a simmering political issue.

Read the rest of the story at Commentary Magazine.

Andy Greenwald, Grantland

On Sunday night, the second season of Showtime’s Homeland, which earned Emmy Awards for Best Drama and for both of its lead actors earlier this year, drew to a close. The series, which chronicles the attempts of bipolar CIA analyst Carrie Mathison (Claire Danes) to protect the United States from international terrorist attacks, has remained a buzzy hit for the channel — but it lost the support of some critics, who felt the show had become implausible during its polarizing second season. Here's a dispatch from the set of Homeland, and an exploration of how the show has managed to stand out in a crowded television schedule:

Homeland's entire second season emerged from the emotional wreckage of an unexploded bomb. Brody lived — thus guaranteeing the show at least another year of Damian Lewis — but his aborted act of terror carried with it its own dangers: Gone was the central is-he-or-isn't-he dynamic that captured hearts and minds last year (outdated spoiler: He was) and in its place were a whole lot of fractured hows. To wit: How would the show refigure itself without its central mystery? How would Carrie — last seen disgraced, unemployed, and zapping her cerebellum like an aging car battery — be brought back into the fold? And, after shooting a deer and punching his best friend, how would Brody find new ways to awkwardly disrupt social events at his house? It turns out we were worried about the wrong things. Despite what happened in the first-season finale, Homeland is defined not by the specifics of its plot or the deviousness of its puzzles, but by the cavalier way it blows things up. Rather than being cowed by the pressures of success, co-executive producers Alex Gansa and Howard Gordon returned fully radicalized, detonating storytelling conventions and audience expectations in the process. Brody's lingering suicide tape? Discovered in Episode 2. Carrie finally snapping the cuffs on her ginger obsession? Done and dusted just two hours later. "You have to be fearless," staff writer Henry Bromell told me, as he watched a scene unfold on the monitors in Video Village. "We're not afraid to eat through story."

Read the rest of the story at Grantland.

Jill Lepore, The New Yorker

The debate over the role of guns in America continued to rage throughout the week in the wake of the tragic Sandy Hook Elementary shootings in Connecticut on Friday, Dec. 14. Politicians, analysts, and the American people continue to weigh the balance between America’s high rate of gun violence and rights guaranteed by the Second Amendment — but what exactly does the Second Amendment guarantee, anyway? Here's an exploration of America’s long, complicated relationship with guns, originally published in the months after the widely publicized Trayvon Martin shooting in Florida:

The Second Amendment reads, "A well-regulated militia being necessary to the security of a free State, the right of the people to keep and bear arms shall not be infringed." Arms are military weapons. A firearm is a cannon that you can carry, as opposed to artillery so big and heavy that you need wheels to move it, or people to help you. Cannons that you can carry around didn’t exist until the Middle Ages. The first European firearms — essentially, tubes mounted on a pole — date to the end of the fourteenth century and are known as "hand cannons." Then came shoulder arms (that is, guns you can shoulder): muskets, rifles, and shotguns. A pistol is a gun that can be held in one hand. A revolver holds a number of bullets in a revolving chamber, but didn’t become common until Samuel Colt patented his model in 1836. The firearms used by a well-regulated militia, at the time the Second Amendment was written, were mostly long arms that, like a smaller stockpile of pistols, could discharge only once before they had to be reloaded. In size, speed, efficiency, capacity, and sleekness, the difference between an eighteenth-century musket and the gun that [alleged Martin shooter] George Zimmerman was carrying is roughly the difference between the first laptop computer — which, not counting the external modem and the battery pack, weighed twenty-four pounds — and an iPhone.

Scott Meslow is the entertainment editor for TheWeek.com. He has written about film and television at publications including The Atlantic, POLITICO Magazine, and Vulture.

-

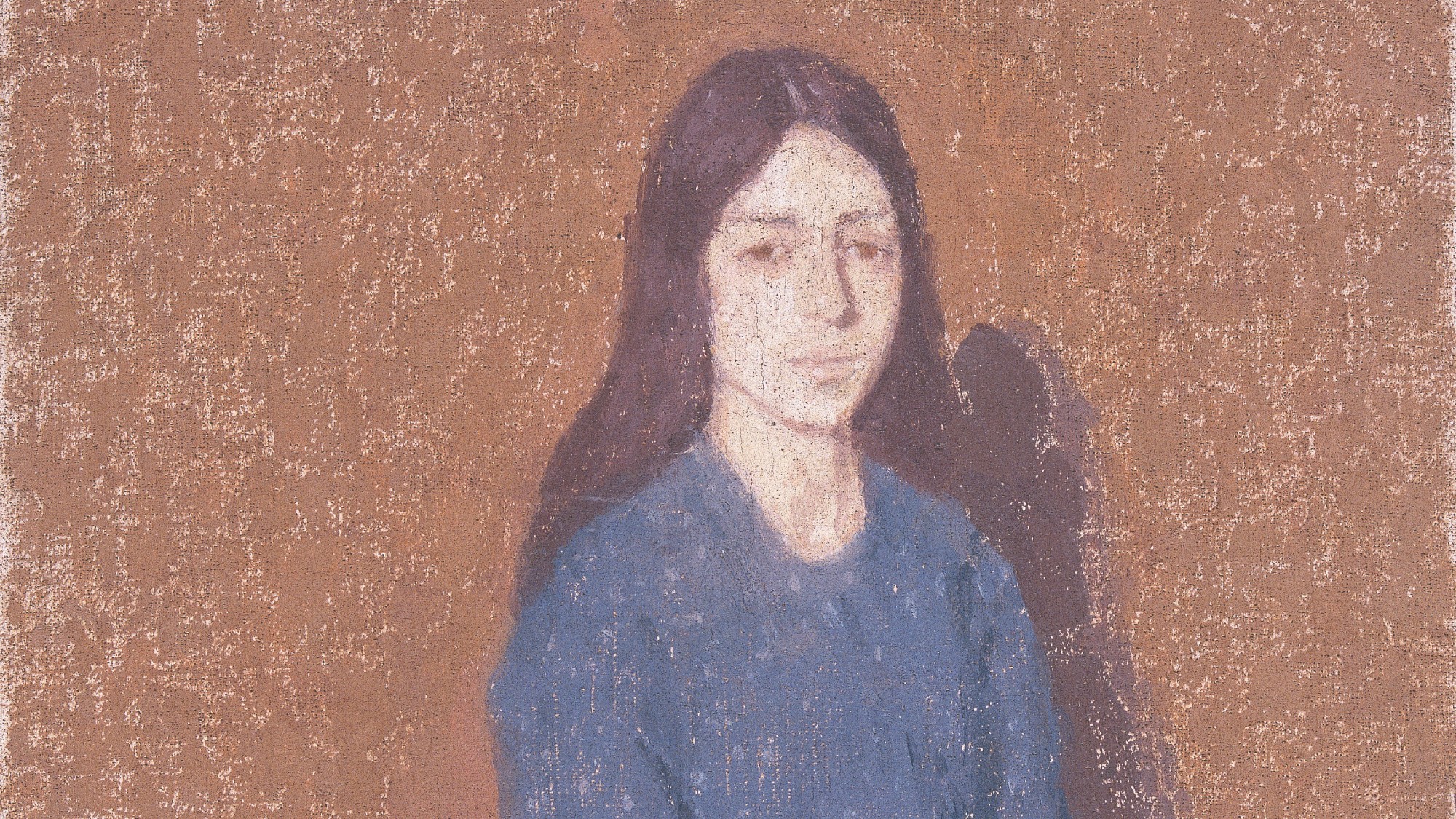

Gwen John: Strange Beauties – a ‘superb’ retrospective

Gwen John: Strange Beauties – a ‘superb’ retrospectiveThe Week Recommends ‘Daunting’ show at the National Museum Cardiff plunges viewers into the Welsh artist’s ‘spiritual, austere existence’

-

Should the EU and UK join Trump’s board of peace?

Should the EU and UK join Trump’s board of peace?Today's Big Question After rushing to praise the initiative European leaders are now alarmed

-

Antonia Romeo and Whitehall’s women problem

Antonia Romeo and Whitehall’s women problemThe Explainer Before her appointment as cabinet secretary, commentators said hostile briefings and vetting concerns were evidence of ‘sexist, misogynistic culture’ in No. 10