Why the U.S. must change its presidential succession rules

It's irrational and dangerous to have a nonagenarian three heartbeats away from the presidency

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Until his death on Monday, Hawaii Sen. Daniel Inouye stood three heartbeats away from the presidency. Because of a very foolish and anachronistic Senate tradition, the longest-serving member of the majority party in the Senate is right behind the vice president and the speaker of the House in the line of succession to the presidency. So in the not-by-any-means-inconceivable possibility of a deadly attack on the federal government that took out the president, VP, and speaker, an 88-year-old would have been president at a moment of the greatest crisis in the country's history. Maybe the only comforting thought is that Inouye was much more prepared than the man he replaced in that role. Nonetheless, its time to reconsider the line of succession before the nation has to deal with a real catastrophe.

Inouye was third in line for the presidency owing to his elected role as Senate president pro tempore. That role, which is the only Senate position mentioned in the Constitution, is a ceremonial job that for the last century or so has been automatically given to the longest-serving member of the majority party. While it may not be an important job in terms of actually running the Senate, the Presidential Succession Act of 1947 placed the president pro tempore after the vice president and speaker of the House in the line of succession for the presidency. Unfortunately, the Senate didn't then decide to actually elect leaders to the role.

The result has been embarrassing, and potentially dangerous. Before Inouye, the president pro tempore was 92-year-old Robert Byrd, who had to be removed from his position as Appropriations Committee chair because he was unable to do that job. A few years before Byrd, Strom Thurmond, who in 1999 proved unable to serve as chairman of the Senate Armed Services Committee, held down the job of president pro tempore.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

The country's leadership always faces mortal threats, and senators who are too out of it to head a committee are near the front of the line to become president.

A decapitating strike is not just some unlikely situation. It actually came close to occurring once before. On April 14, 1865, John Wilkes Booth killed President Abraham Lincoln. One of the assassin's colleagues stabbed and wounded Secretary of State William Seward. General Ulysses S. Grant was supposed to be killed with Lincoln, but he changed his plans and did not attend the play. Vice President Andrew Johnson's would-be assassin lost his nerve and spent the night drinking. This multi-assassination plot should serve as a reminder of just how important it is to prepare for catastrophe.

What makes this all the more surprising is that there is no Constitutional requirement that would place an enfeebled man so high up in the line of succession. The presidential succession laws can be changed by acts of Congress, and have been numerous times in the past.

In the original law, in place from 1792 to 1886, the president pro tempore was second in line, before the speaker, for the presidency. In 1886, after a 21-year period in which two presidents were assassinated, two vice presidents died of natural causes, and one president was impeached (with his potential replacement, Senate President Pro Tempore Benjamin Wade, sitting in judgment), Congress decided to change the law, putting cabinet members, starting with the secretary of state, first in line for succession. The law was changed back in 1947, placing the speaker of the House before the Senate president pro tempore.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

There is legitimate debate as to whether it makes sense for congressional leaders to be at the front of the succession line. Harry Truman, among others, believed that congressional leaders should be, simply because they are elected and not appointed. On the other hand, the Continuity of Government Commission argues that cabinet members should be first, in part to ensure that the president's party does not lose power in case of a major tragedy.

Both arguments have their merits. But what is truly critical is ensuring that the people in line are able to lead our nation and world in a time of great crisis. While Daniel Inouye was clearly a truly exceptional war hero and senator, by his late 80s, he may no longer have met this most basic criterion. Certainly Robert Byrd and Strom Thurmond would not have been up to the challenge.

There are very easy answers to this problem. Either change back to the "cabinet members first" rule, or change who is elected to the position of Senate president pro tempore (in this case, it should be the Senate majority leader). The second option would at least ensure that the true head of the Senate, a presumably fully capable person that the senators selected to lead them, would be the person in line for the presidency should disaster strike.

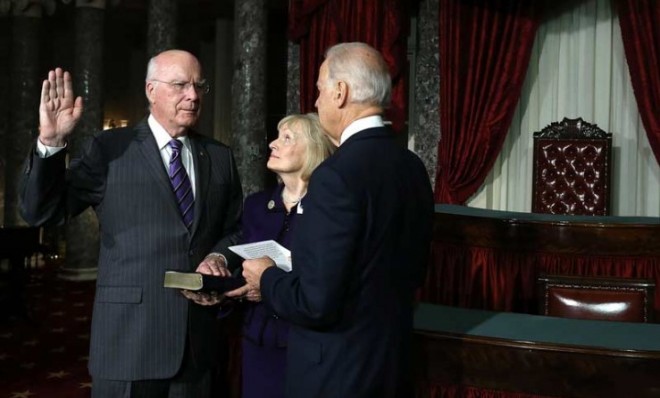

With Inouye's death, the new president pro tempore, Senator Patrick Leahey, is a relatively spry 72, so the crisis is no longer there. But we still must change the rules to make sure that the line of succession is filled with people who are alert and able to take control.

Joshua Spivak is a senior fellow at the Hugh L. Carey Institute for Government Reform at Wagner College. He writes the Recall Elections Blog.

Joshua Spivak is a senior fellow at the Hugh L. Carey Institute for Government Reform at Wagner College in New York, and writes The Recall Elections Blog.

-

Rubio boosts Orbán ahead of Hungary election

Rubio boosts Orbán ahead of Hungary electionSpeed Read Far-right nationalist Prime Minister Viktor Orbán is facing a tough re-election fight after many years in power

-

Hyatt chair joins growing list of Epstein files losers

Hyatt chair joins growing list of Epstein files losersSpeed Read Thomas Pritzker stepped down as executive chair of the Hyatt Hotels Corporation over his ties with Jeffrey Epstein and Ghislaine Maxwell

-

Political cartoons for February 17

Political cartoons for February 17Cartoons Tuesday’s political cartoons include a refreshing spritz of Pam, winter events, and more

-

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?Talking Point Peter Thiel and Larry Page preparing to change state residency

-

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one report

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one reportIN THE SPOTLIGHT By blocking an approved segment on a controversial prison holding US deportees in El Salvador, the editor-in-chief of CBS News has become the main story

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June

-

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardon

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardonTalking Point Convicted sex trafficker's testimony could shed new light on president's links to Jeffrey Epstein

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred