Aid to the world

The budget debate has sharpened scrutiny of U.S. foreign aid. Are we getting our money’s worth?

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Why do we send money to foreign countries?

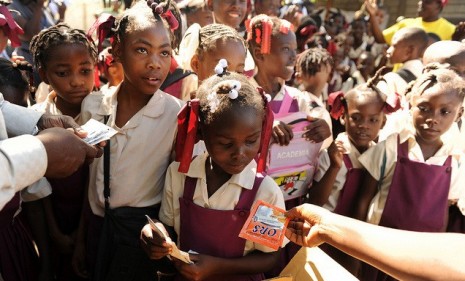

The U.S. government cites two reasons: National security and humanitarian concerns. The top aid recipients are strategically important countries where the U.S. wants to safeguard vital economic interests, counter al Qaida, or stanch the flow of drugs. “Economic development is a lot cheaper than sending soldiers,” Secretary of Defense Robert Gates said recently. Aid flows as well in smaller quantities to the poorest of the poor in sub-Saharan Africa, where the focus is on food and medical assistance and the fight against AIDS.

How much do we spend on foreign aid?

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Far less than we think. Polls have consistently found that Americans believe around a quarter of the U.S. budget goes to foreign aid, and respondents say we ought to spend at most half that much. In fact, foreign aid accounts for about 1.1 percent of the budget, or $39.4 billion, and a quarter of that is military aid. In absolute terms, the U.S. is the world’s most generous country, but as a percentage of national income, our foreign aid budget is stingier than that of any wealthy country but South Korea. Great Britain and France each spend at about twice the rate of the United States, where foreign aid outlays come to less than 40 cents per citizen per day.

Where does it all go?

Egypt and Israel have traditionally been among the top aid recipients, but since 9/11, foreign aid budgets have tripled and shifted, especially toward Afghanistan and Pakistan. Afghanistan in 2009 received the largest amount—more than $3 billion in economic assistance and $5.7 billion in military assistance. Some of that money flows straight to Afghan government institutions in the form of cash, and many suspect that some of it flows out the same way: WikiLeaks revealed a U.S. Embassy cable stating that an Afghan vice president had been discovered in 2009 transporting $52 million in cash to Dubai. Another cable detailed how the governor of one province skimmed funds from U.S. development projects by threatening contractors until they gave him cash.

Is waste like that an exception?

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Yes. But there are nagging questions. A Brookings Institution report last year found that the U.S. ranked worst of all international donors in following up on who, exactly, receives its money. Definitions of waste differ, too. Rep. Ron Paul, for example, opposes all foreign aid, calling it a doomed “attempt to purchase friends.” Others argue that even when U.S. dollars go to a good cause, they allow unscrupulous rulers to waste money in other ways. Republican Rep. Ed Royce complained last month that the government had given $540 million to Senegal, which in turn spent $28 million of its own money on a bombastic “African Renaissance” monument larger than the Statue of Liberty—and built by North Koreans. “Our U.S. taxpayers put money into Senegal, and that frees up money for this kind of an operation,” Royce said. On the other hand, U.S. funding to Senegal and other poor countries unquestionably saves lives. And there is no compelling evidence that foreign aid is any more prone to waste than, say, military expenditures are.

Will Congress cut foreign aid?

It aims to. Kay Granger, the Texas Republican who chairs the House subcommittee that appropriates funds for foreign aid, promises “painful cuts” to programs that don’t affect “direct national security,” especially expenditures for food and climate-change programs. She’s backing a bill to cut $121 million—about 9 percent—of the budget of the U.S. Agency for International Development, even as she acknowledges “a huge misunderstanding” on the part of people who believe that cuts to such spending can resolve budget deficits. Republicans contend that with Americans out of work and the country deeply in debt, the U.S. can no longer afford to provide handouts.

Is there pushback?

Plenty, including from the Pentagon. Gen. David Petraeus, commander of U.S. and NATO forces in Afghanistan, warned Congress last month that “inadequate resourcing of our civilian partners” could “jeopardize accomplishment of the overall mission.” Others contend that foreign aid to poor countries is not only a moral imperative, but also a small investment that yields a huge payoff. “The 1 percent we spend on aid for the poorest not only saves millions of lives,” says Microsoft founder Bill Gates, “it has an enormous impact on developing economies—which means it has an impact on our economy.”

Aid to fight AIDS

“Even people who are snide and snarky about the United States of America have to admit that millions and millions of lives have been saved by American taxpayers,” rock star Bono told Fox News last year. He and other development activists have particularly praised former President George W. Bush for launching a multiyear, multibillion-dollar commitment to fight AIDS in Haiti, Guyana, Vietnam, and 12 African countries. In its first five years, the program spent nearly $20 billion to purchase and distribute anti-retroviral drugs to some 2 million HIV-positive people, more than half of them pregnant women. Thanks to the drugs, nearly 250,000 babies born to HIV-positive mothers were HIV-free. And over the first five years, the AIDS death rate in those countries dropped more than 10 percent. “I was acting on national security concerns,” Bush said. “There’s nothing more hopeless than for a child to watch mom and dad die of AIDS and nobody helped, particularly the wealthy nations. And the enemy we face can only recruit when they find hopeless people.”