Exhibit of the week: The Darker Side of Light: Arts of Privacy, 1850–1900

The intimate prints on display at the National Gallery of Art reveal a melancholy side to the late 19th century that is quite different from the “light-filled scenes” of the impressionists.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

Through Jan. 18, 2010

This intimate exhibition of prints, etchings, and small sculptures “very definitely caters to mature audiences,” said Michael O’Sullivan in The Washington Post. Packed into three small rooms at the National Gallery of Art, these 100 or so works feature “male and female nudity, sensuality, violence, and drug use.” Albert Besnard’s dark etchings depict shadowy scenes of rape, opium addiction, and suicide. Two François-Nicolas Chifflart works gruesomely depict an 1865 cholera epidemic in Paris. Eugène Carrière’s Sleep—“an 1890 lithograph of a woman laying her head in weariness upon her folded hands”— simply seems otherworldly. Juxtaposing fantastic visions with dark depictions of the everyday, this collection provides a “wonderfully perverse—yet surprisingly mesmerizing”—peek into the late 19th-century mind.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

One look at these shadowy visions and “you’ll never think of the 19th century the same way again,” said Karen Wilkin in The Wall Street Journal. Most museumgoers today associate that era with the “light-filled scenes” of the impressionists, which could not be more different. This compact but daring exhibit “challenges the dominance of impressionism’s cheerful world of public spectacle” by emphasizing psychological depths and melancholy moods. Some artists’ styles are familiar, such as Edvard Munch’s “predatory women and Odilon Redon’s hallucinatory inventions.” But several of the most compelling works are surprises from lesser known artists. Fernand Khnopff’s conté crayon drawing of a canal lingers “like an imperfectly remembered dream,” while Louis-Ernest Barrias gives one “kinky” sculpture the seemingly innocuous title Nature Unveiling Herself Before Science. “For sheer oddness, it’s hard to beat.” Yet it’s the precocious protosurrealist Max Klinger who is the true “star of the show.”

The prints from Klinger’s “Glove” series turn out to be “some of the most haunting” works in the entire exhibit, said Chris Klimek in The Washington Examiner. “Inspired by a dream he had in 1878 of pursuing a woman’s elbow-length glove,” they tell an absurd but involving story that seems plucked directly from the artist’s subconscious. “When the glove is snatched away by a dragon-like creature—well, better if you just go see it.” Another interesting point this exhibition makes is that even artists we traditionally associate with impressionism, such as Edgar Degas and Mary Cassatt, had their darker sides. Their intimate scenes of private reverie are as “mournful and psychologically intense” as any work here.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

-

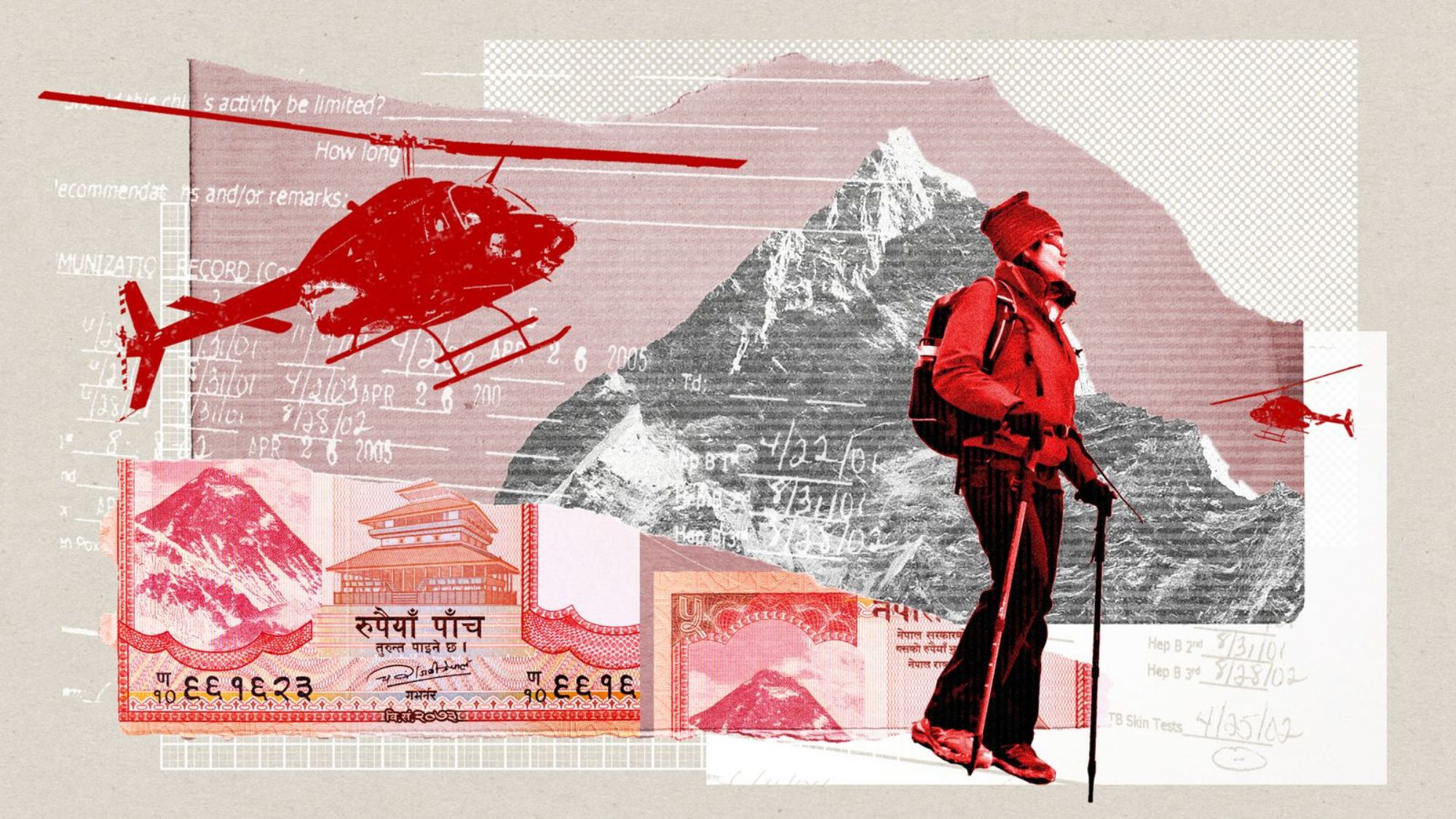

Nepal’s fake mountain rescue fraud

Nepal’s fake mountain rescue fraudUnder The Radar Arrests made in alleged $20 million insurance racket

-

History-making moments of Super Bowl halftime shows past

History-making moments of Super Bowl halftime shows pastin depth From Prince to Gloria Estefan, the shows have been filled with memorable events

-

The Washington Post is reshaping its newsroom by laying off hundreds

The Washington Post is reshaping its newsroom by laying off hundredsIn the Spotlight More than 300 journalists were reportedly let go

-

If/Then

feature Tony-winning Idina Menzel “looks and sounds sensational” in a role tailored to her talents.

-

Rocky

feature It’s a wonder that this Rocky ever reaches the top of the steps.

-

Love and Information

feature Leave it to Caryl Churchill to create a play that “so ingeniously mirrors our age of the splintered attention span.”

-

The Bridges of Madison County

feature Jason Robert Brown’s “richly melodic” score is “one of Broadway’s best in the last decade.”

-

Outside Mullingar

feature John Patrick Shanley’s “charmer of a play” isn’t for cynics.

-

The Night Alive

feature Conor McPherson “has a singular gift for making the ordinary glow with an extra dimension.”

-

No Man’s Land

feature The futility of all conversation has been, paradoxically, the subject of “some of the best dialogue ever written.”

-

The Commons of Pensacola

feature Stage and screen actress Amanda Peet's playwriting debut is a “witty and affecting” domestic drama.