George Carlin

The subversive comedian who honored no sacred cows

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The subversive comedian who honored no sacred cows

George Carlin

1937–2008

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

George Carlin, who died this week of heart failure, was, along with Lenny Bruce and Richard Pryor, a pioneer of subversive stand-up comedy. With blue language and irreverent social insights, he broke with the buttoned-down respectability of such mainstream performers as Bob Newhart, creating routines that tested the limits of free speech and good taste. “I think it is the duty of the comedian to find out where the line is drawn—and cross it deliberately,” he once said.

Carlin’s comedy was originally based on “clever wordplay and reminiscences of his Irish working-class upbringing in New York,” said The New York Times. One of his iconic characters was Al Sleet, the Hippy-Dippy Weatherman, who would say, “Tonight’s forecast: Dark. Continued dark throughout most of the evening, with some widely scattered light toward morning.” His offbeat persona won him a recurring role as Marlo Thomas’ agent on That Girl and more than 80 spots on The Ed Sullivan Show, The Tonight Show, and other TV mainstays. But Carlin found mainstream acceptance “as dinky and hollow as a gratuitous pratfall,” saying later, “I was a traitor, in so many words. I was living a lie.” So in 1970, he traded his suit and clean-cut persona for “a beard, long hair, and jeans,” as his observational humor focused on such hot-button issues as drugs, the war in Vietnam, religion, and sex.

The backlash was immediate, said Time. Carlin was thrown out of Las Vegas twice and temporarily banned by Johnny Carson. But he soon found his niche in coffeehouses, concert halls, and on college campuses, challenging conventional wisdom and attacking what he considered the prevailing hypocrisy. “He made fun of society’s outrage over drugs, for example, pointing out that the ‘drug problem’ extends to middle-class America as well, from coffee freaks at the office to housewives hooked on diet pills.” When NBC unveiled a new, late-night guerrilla comedy program called Saturday Night Live in 1975, Carlin was picked as its first guest host. He would have a lasting effect on American law as well as comedy. In one of his classic routines, he recited the “seven words you can never say on television.” That routine got him arrested on obscenity charges and also led to a lawsuit that eventually made its way to the U.S. Supreme Court. In a 5–4 vote in 1978, the court ruled that the Federal Communications Commission could ban certain words from the airwaves. “My name is a footnote in American legal history,” Carlin reflected, “which I’m perversely kind of proud of.”

“Carlin produced 23 comedy albums, appeared in 16 films and 14 HBO specials, wrote five books, and had more television appearances than Wikipedia can count,” said the Baltimore Sun. But he had his troubles, too. At various times he was addicted to cocaine, Vicodin, and alcohol; suffered three heart attacks; and had two open-heart surgeries. Increasingly, his routines resembled rants, and many critics found his anger to be off-putting. “What I have that’s often mistaken for anger is a disappointment and disillusionment,” he remarked, “a severe disillusionment with my species and my culture.” But Carlin remained a versatile “cross-genre comedian,” appealing to children on such shows as Thomas the Tank Engine & Friends while also making their parents laugh by ruminating, “If all the world is a stage, where is the audience sitting?” or “Do infants enjoy infancy as much as adults enjoy adultery?”

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Carlin won four Grammy Awards, and this fall he was scheduled to receive the Mark Twain Prize for American Humor at the Kennedy Center. When he heard the news, he responded, “Thank you, Mr. Twain. Have your people call my people.”

-

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?IN THE SPOTLIGHT As the president muses about polling place deployments and a centralized electoral system aimed at one-party control, lawmakers are taking this administration at its word

-

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

Earth is rapidly approaching a ‘hothouse’ trajectory of warming

Earth is rapidly approaching a ‘hothouse’ trajectory of warmingThe explainer It may become impossible to fix

-

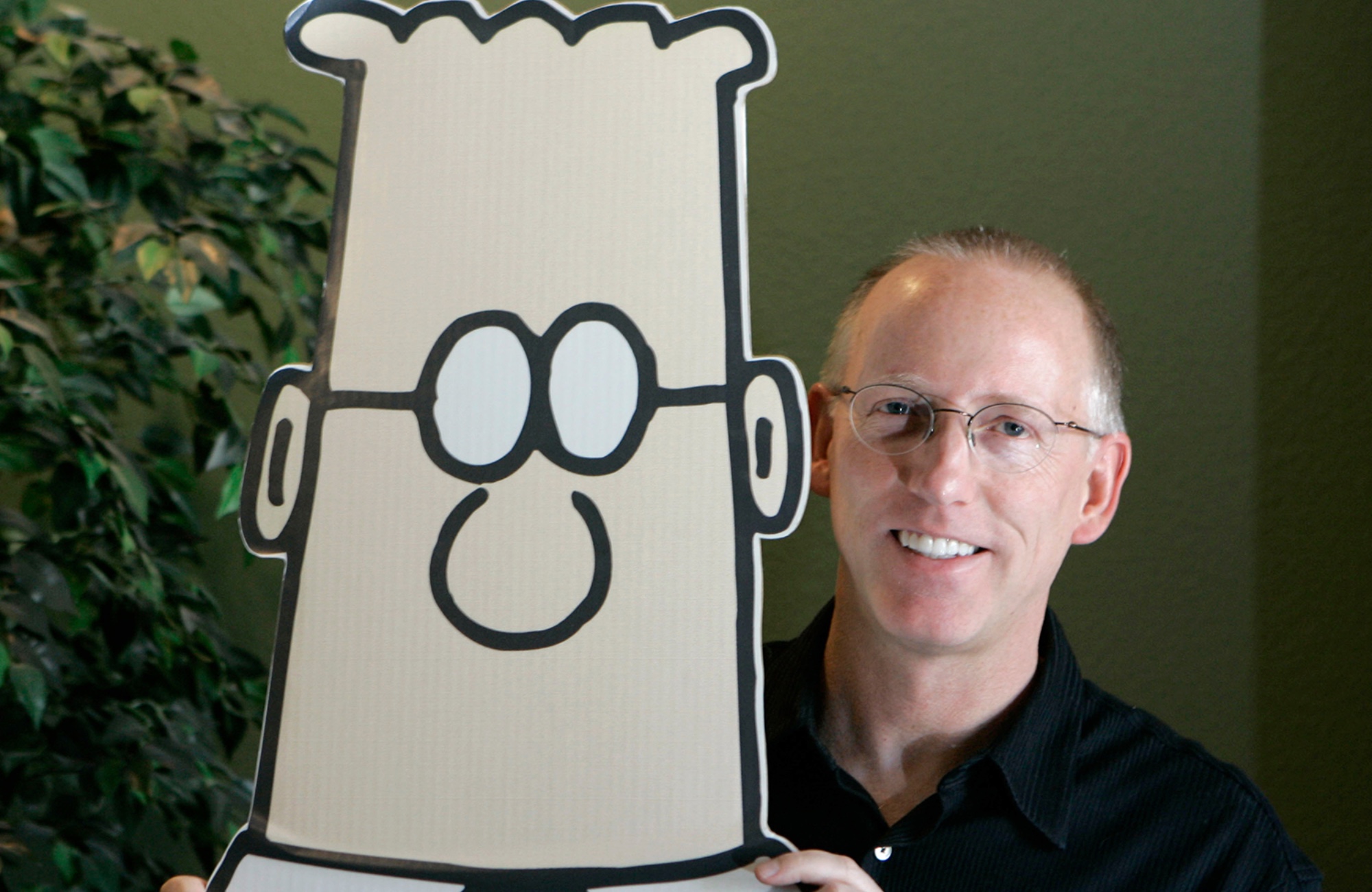

Scott Adams: The cartoonist who mocked corporate life

Scott Adams: The cartoonist who mocked corporate lifeFeature His popular comic strip ‘Dilbert’ was dropped following anti-Black remarks

-

Bill Moyers: the journalist who was the face of PBS

Bill Moyers: the journalist who was the face of PBSFeature A legend in public broadcasting

-

Ruth Buzzi: The comic actress who packed a wallop

Ruth Buzzi: The comic actress who packed a wallopFeature She was best-known as Gladys Ormphby on the NBC sketch show "Rowan & Martin's Laugh-In"

-

Val Kilmer: the actor who played Iceman and Batman

Val Kilmer: the actor who played Iceman and BatmanFeature Kilmer died at age 65 from pneumonia

-

David Brenner, 1936–2014

feature The comedian who ruled ‘The Tonight Show’

-

Dr. Joyce Brothers, 1927–2013

feature The psychologist who became a media star

-

Phyllis Diller, 1917–2012

feature The comedian who paved the way for female stand-up

-

Leo Kirch, 1926–2011

feature The man who built and lost a media empire