The dangers of our aging nuclear arsenal

Outdated and underfunded, America's decrepit nuclear program could be one mishap away from catastrophe

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

How bad is the situation?

The Pentagon recently admitted there are "systemic problems across the nuclear enterprise." Thanks to arms-control treaties and the end of the Cold War, the U.S. has reduced its stockpile of nuclear weapons from 31,000 to about 4,800 over the last 48 years. But as fears of nuclear war eased, the government failed to adequately maintain and update this immensely dangerous arsenal, which still contains enough collective destructive force to lay waste to every country on Earth. The U.S.'s 450 intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs) are stored in decaying 60-year-old nuclear silos in Montana, North Dakota, and Wyoming that look like a poorly maintained Cold War museum. The demoralized Air Force personnel safeguarding the weapons have been plagued by scandals reaching to the very top of the command structure — including drug rings, mislaid missiles, and widespread cheating on readiness tests. Today, the real nuclear threat to America isn't an enemy strike, says Air Force Lt. Gen. James Kowalski. It's "an accident. The greatest risk…is doing something stupid."

How old are America's nukes?

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

The average age of a U.S. nuclear warhead is 27 years. Many of the buildings where the nuclear missiles and bombs are stored date back to the 1950s — and it shows. Blast doors on the country's nuclear missile silos are too rusty to seal shut. The roof of a security complex in Oak Ridge, Tenn., that houses most of the U.S. supply of enriched uranium collapsed in March. For years, the three ICBM complexes had just one working wrench available to tighten the bolts on the missiles' warheads. When the wrench was needed, the workers would FedEx it from base to base. Today, the principal information technology used to operate and launch the ICBMs is an 8-inch floppy disk from the 1960s.

Is the staff demoralized?

That's an understatement. The Air Force officers spend long shifts in a hole underground waiting for a launch order that will probably never come, while "their buddies from the B-52s and B-2s tell them all sorts of exciting stories about doing real things in Afghanistan and Iraq," Hans Kristensen, director of the Federation of American Scientists' Nuclear Information Project, told Mother Jones. That sense of frustration has led to trouble. In 2013, the Pentagon announced it was investigating a drug ring across six missile launch facilities. Then, when examining the phones of two Montana officers suspected of using ecstasy and amphetamines, Air Force commanders unwittingly uncovered a cheating scandal implicating 98 missileers. The officers had been texting one another the answers for the monthly exams, which test a missileer's knowledge of security procedures and classified launch codes. The institutional rot has led to a number of frightening near-misses.

Such as?

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

In 2007, six nuclear missiles went missing from a North Dakota facility for 36 hours. It turned out they'd been accidentally attached to a plane's wings and flown over several states to Louisiana, where they were left sitting unprotected on the tarmac for hours. A year before, four missile nose cones were accidentally sent to Taiwan instead of helicopter batteries. The most serious near-disaster occurred back on Jan. 21, 1961, when two nuclear bombs slipped from the belly of a B-52 flying over the North Carolina city of Goldsboro. Both bombs were set to detonate, and failed to do so after suffering minor damage to the parts needed to initiate an explosion — a stroke of luck that saved the city from annihilation.

What's being done to improve the situation?

Before announcing his resignation in November, Defense Secretary Chuck Hagel announced $7.5 billion in extra funding over five years to cover management changes, training, and weapons upgrades. He was following the lead of President Obama, who has reversed his 2009 pledge to seek a "world without nuclear weapons." Not only has Obama overseen the slowest five-year reduction of warheads in the past 20 years, but the president has also called for $1 trillion in nuclear modernization over 30 years, with a commitment to 400 land-based missiles, 100 new bombers, and 12 new missile-firing submarines. Some defense experts think he's foolish to try to maintain a vast nuclear force created for 20th-century superpower threats. "It's not missileers who are at fault; it's the mission," says Joseph Cirincione, a global security expert and author of the book Nuclear Nightmares.

What do hawks say?

They point to recent world events — such as the standoff with Russia over Ukraine and the volatility of nuclear-armed North Korea — as a reason for America to maintain a strong nuclear deterrent. Still, former Vice Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Gen. James Cartwright thinks the U.S. should eliminate ICBMs entirely and focus on smaller "tactical" nuclear weapons, such as plane-carried bombs. But for the foreseeable future, says Pentagon adviser Joe Braddock, the U.S. will try to keep its existing arsenal from falling apart. "The interesting thing about a nuclear deterrent is that enough of it has to be visible to scare the living daylights out of the enemy," he says. "But if you are not careful, you scare the living daylights out of yourself."

The world's most tedious job

Overseeing the country's nuclear missiles sounds like a thrilling job — in theory. But the workday of an average missileer is, in fact, mind-numbingly tedious. Air Force personnel have to work grueling 24-hour shifts inside a cramped capsule buried 60 feet underground, completing checklist after monotonous checklist. The air in the capsule is recycled and stale, with only a tiny prison toilet shared between officers. When problems arise, the missileers have no choice but to improvise: When two sewer pipes ruptured at a Montana launch facility, officers were forced to defecate into a cardboard box lined with a plastic bag — a demeaning situation that went on for months. "You are sitting there being told you are operating the most vital system to the defense of the country," a former missileer told Mother Jones, "and there you are s----ing and pissing in a bag."

-

How to juggle saving and paying off debt

How to juggle saving and paying off debtthe explainer Putting money aside while also considering what you owe to others can be a tricky balancing act

-

Hong Kong jails democracy advocate Jimmy Lai

Hong Kong jails democracy advocate Jimmy LaiSpeed Read The former media tycoon was sentenced to 20 years in prison

-

Japan’s Takaichi cements power with snap election win

Japan’s Takaichi cements power with snap election winSpeed Read President Donald Trump congratulated the conservative prime minister

-

The recycling crisis

The recycling crisisThe Explainer Much of the stuff Americans think they are "recycling" now ends up in landfills and incinerators. Why?

-

The L.A. teachers strike, explained

The L.A. teachers strike, explainedThe Explainer Everything you need to know about the education crisis roiling the Los Angeles Unified School District

-

The NSA knew about cellphone surveillance around the White House 6 years ago

The NSA knew about cellphone surveillance around the White House 6 years agoThe Explainer Here's what they did about it

-

America's homelessness crisis

America's homelessness crisisThe Explainer The number of homeless people in the U.S. is rising for the first time in years. What’s behind the increase?

-

The truth about America's illegal immigrants

The truth about America's illegal immigrantsThe Explainer America's illegal immigration controversy, explained

-

Chicago in crisis

Chicago in crisisThe Explainer The "City of the Big Shoulders" is buckling under the weight of major racial, political, and economic burdens. Here's everything you need to know.

-

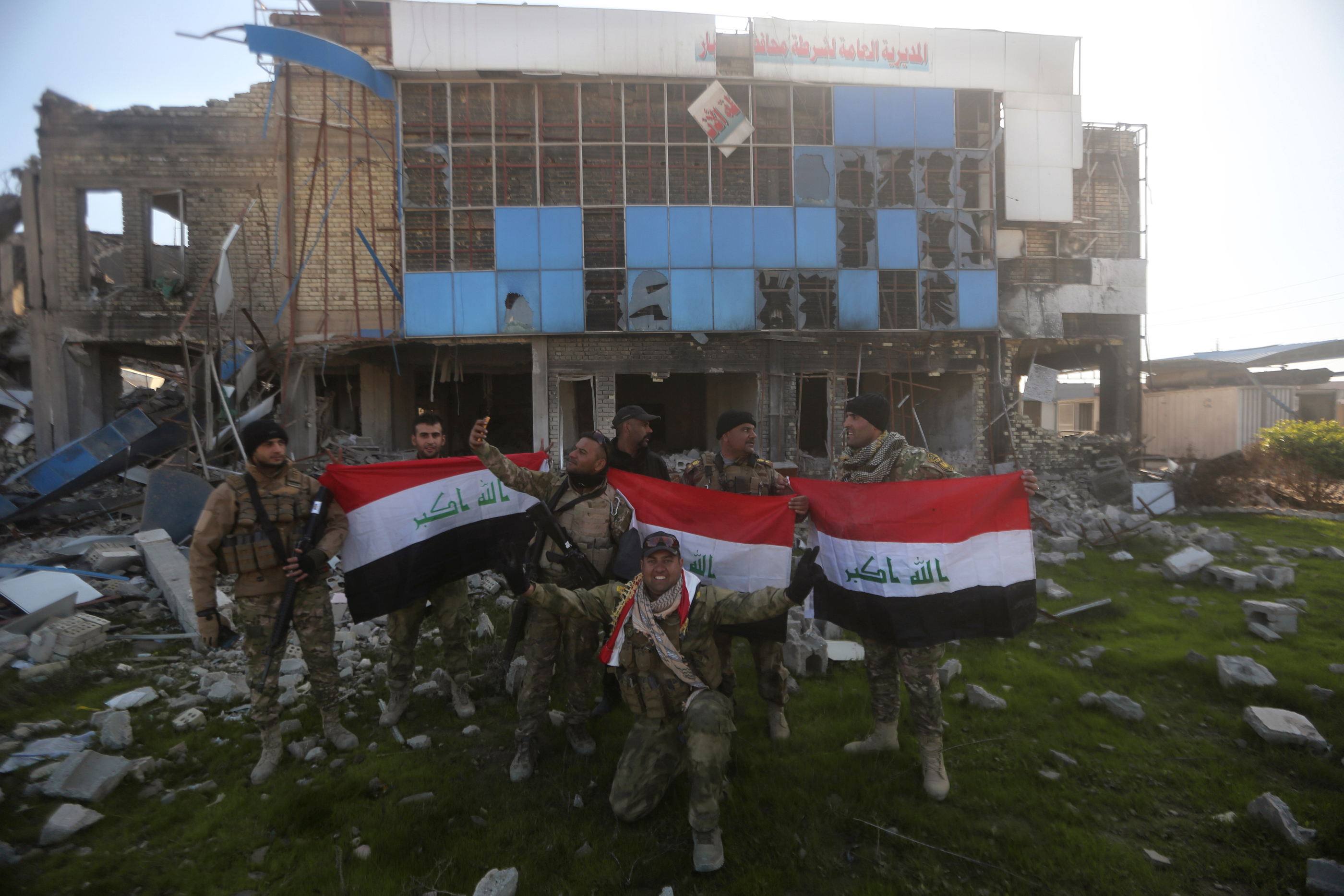

The bad news about ISIS's defeat in Ramadi

The bad news about ISIS's defeat in RamadiThe Explainer The contours of a broader sectarian war are coming into focus

-

America can still destroy the world

America can still destroy the worldThe Explainer The decline of U.S. military power has been greatly exaggerated