ISIS has inadvertently sent Japan a blunt message: Militarize

Japan wants to be a global player without hard power. That's not going to work.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The past week has been a wakeup call to the Japan of Prime Minister Shinzo Abe and a rough introduction to the world of unintended consequences. Days after showing two kidnapped Japanese nationals in a ransom video, ISIS announced that it had executed one, Haruna Yukawa, and threatened to behead another, Kenji Goto, if its demands are not met.

The crisis is a serious complication for Abe, who is pushing his country to become more involved in world affairs. It highlights how unprepared the third largest economy in the world is for political and military crises on the other side of the world. Will the hostage situation change Japanese plans to become a global player?

After World War II, Japan kept a low profile internationally, concentrating on rebuilding the country and raising the standard of living. Japan's constitution forbade it from using military force abroad. It largely followed the lead of the United States on various global issues, while not becoming directly embroiled in them.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

The 1991 Persian Gulf War was a watershed moment for the country. Japan contributed billions to the war effort without deploying troops. Stung by international criticism of "checkbook diplomacy," Japan began sending military personnel on peacekeeping and nation-building missions in places such as Cambodia, Sudan, the Golan Heights, and Haiti.

Prime Minister Abe has sought to accelerate the process. Seeking to contribute to the anti-ISIS coalition, Japan pledged $200 million in aid to refugees and those affected by the war against the Islamist group.

In a clear signal it did not appreciate the Japanese government's meddling, ISIS released a video of captives Yukawa and Goto in orange jumpsuits similar to those worn by executed westerners. ISIS demanded $200 million in ransom or the men would be beheaded.

After the reported execution of Yukawa, ISIS replaced the ransom demand with a proposed deal that would see the remaining hostage Goto freed in exchange for the release of Sajida al-Rishawi, a female member of Al Qaeda imprisoned in Jordan.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

The likelihood of Japan rescuing the remaining hostage is zero. Japan has its own elite Special Forces Group, but it has little to no operational experience. The Japanese government is unfamiliar with the region in general and has no useful assets in place. It has no strong ties to local countries that could host a rescue mission.

The Abe administration has been criticized for its handling of the crisis, particularly for consulting with traditional allies the United States and the United Kingdom instead of regional powers. Although Japan insisted it wanted to negotiate, neither the U.S. nor the U.K. has the direct links necessary to open negotiations with ISIS. In fact, both are combatants in the undeclared war against the self-declared caliphate.

This is not the first time Japan's limited reach has been painfully on display. In January 2013, 10 Japanese hostages were killed after Islamist guerrillas took over an oil refinery in Algeria.

The question is how will Japan respond to these crises in the long term. The easy thing to do is to recoil from the Middle East and North Africa and go back to minding its own fences.

Yet it's clear that Japan's global presence cannot remain limited indefinitely. Japan's prosperity at home is linked to the global economic system, which is in turn affected by events in the Middle East and elsewhere. Furthermore, the world can benefit immensely from Japan's generosity: Japan contributed nearly $5 billion to humanitarian projects in Afghanistan, with another $3 billion by 2017.

The lesson is clear: The old system of following the United States without carrying risk is not going to work anymore. If Japan is to become a global player, it will have to expand its diplomatic relations abroad, identifying key regional players such as Jordan and Turkey in places it wants to have an increased role. It will have to maintain relations with countries independent of its alliance with the United States. And, it will have to be able to realistically assess threats and responses to Japan, mitigating second order effects such as the kidnapping of Yukawa and Goto.

That's not all. If Japan is to continue to push being a global player, it will have to match soft power developments with hard. This crisis won't be the last time Japanese citizens will be threatened abroad, and diplomacy and regional ties can't be counted on to save them. A more visible Japan will have to develop the ability to project power. It will have to be able to project military force abroad to protect and save its citizens.

Japan, which already under-engages the world for a country of its economic stature, is only beginning to match its involvement with its interests. The kidnapping of Goto and Yukawa has been a blunt warning to Tokyo of the consequences involved.

Japanese investments in Japanese soft and hard power seem inevitable. Unless it is willing to retreat from the global stage Japan has little choice but to grimly accept that such events will happen yet again and prepare for the future.

Kyle Mizokami is a freelance writer whose work has appeared in The Daily Beast, TheAtlantic.com, The Diplomat, and The National Interest. He lives in San Francisco.

-

6 of the world’s most accessible destinations

6 of the world’s most accessible destinationsThe Week Recommends Experience all of Berlin, Singapore and Sydney

-

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule works

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule worksIn the Spotlight The law is at the heart of the Colbert-CBS conflict

-

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?Today’s Big Question Democrats want to rein in ICE’s immigration crackdown

-

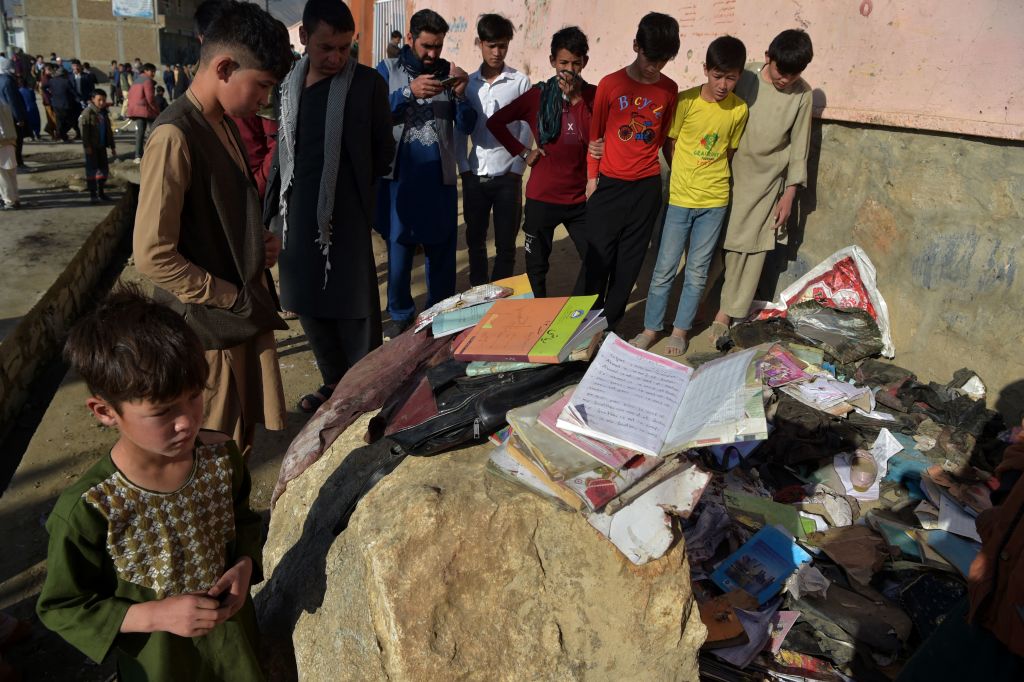

Bombing at girls' school in Kabul kills at least 50, including students

Bombing at girls' school in Kabul kills at least 50, including studentsSpeed Read

-

Garland says DOJ is 'pouring its resources' into stopping domestic terrorists 'before they can attack'

Garland says DOJ is 'pouring its resources' into stopping domestic terrorists 'before they can attack'Speed Read

-

Suspected Israeli cyberattack on Iranian nuclear site complicates U.S.-Iran nuclear deal talks

Suspected Israeli cyberattack on Iranian nuclear site complicates U.S.-Iran nuclear deal talksSpeed Read

-

North Korea fires 2 ballistic missiles into sea

North Korea fires 2 ballistic missiles into seaSpeed Read

-

U.S. airstrikes target Iranian-backed militia facilities in Syria

U.S. airstrikes target Iranian-backed militia facilities in SyriaSpeed Read

-

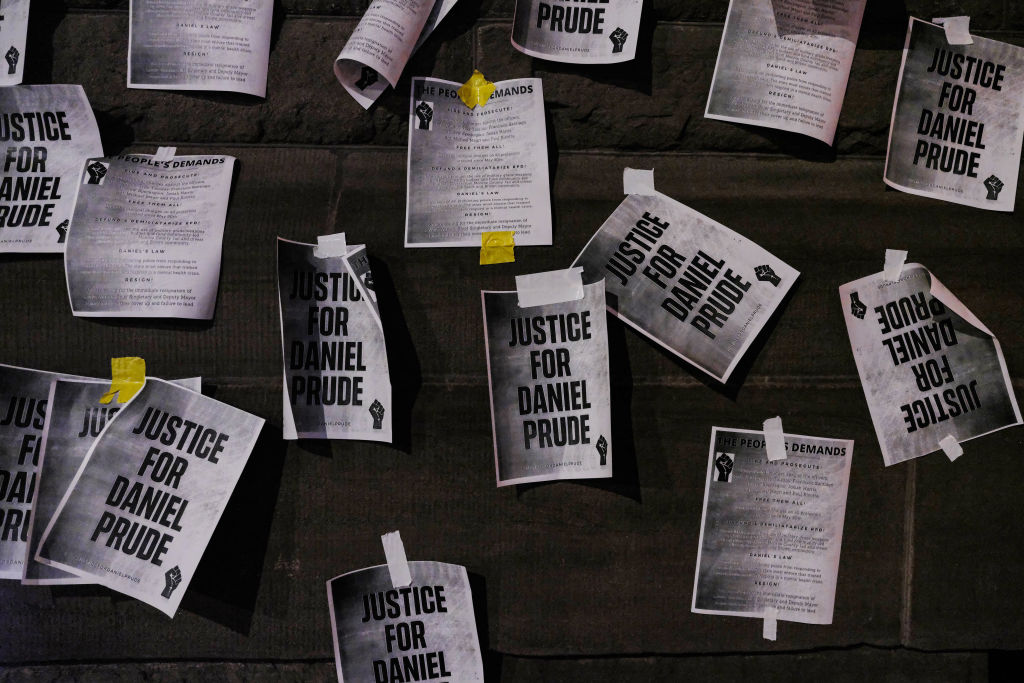

Rochester police who killed Daniel Prude during mental health crisis won't face charges

Rochester police who killed Daniel Prude during mental health crisis won't face chargesSpeed Read

-

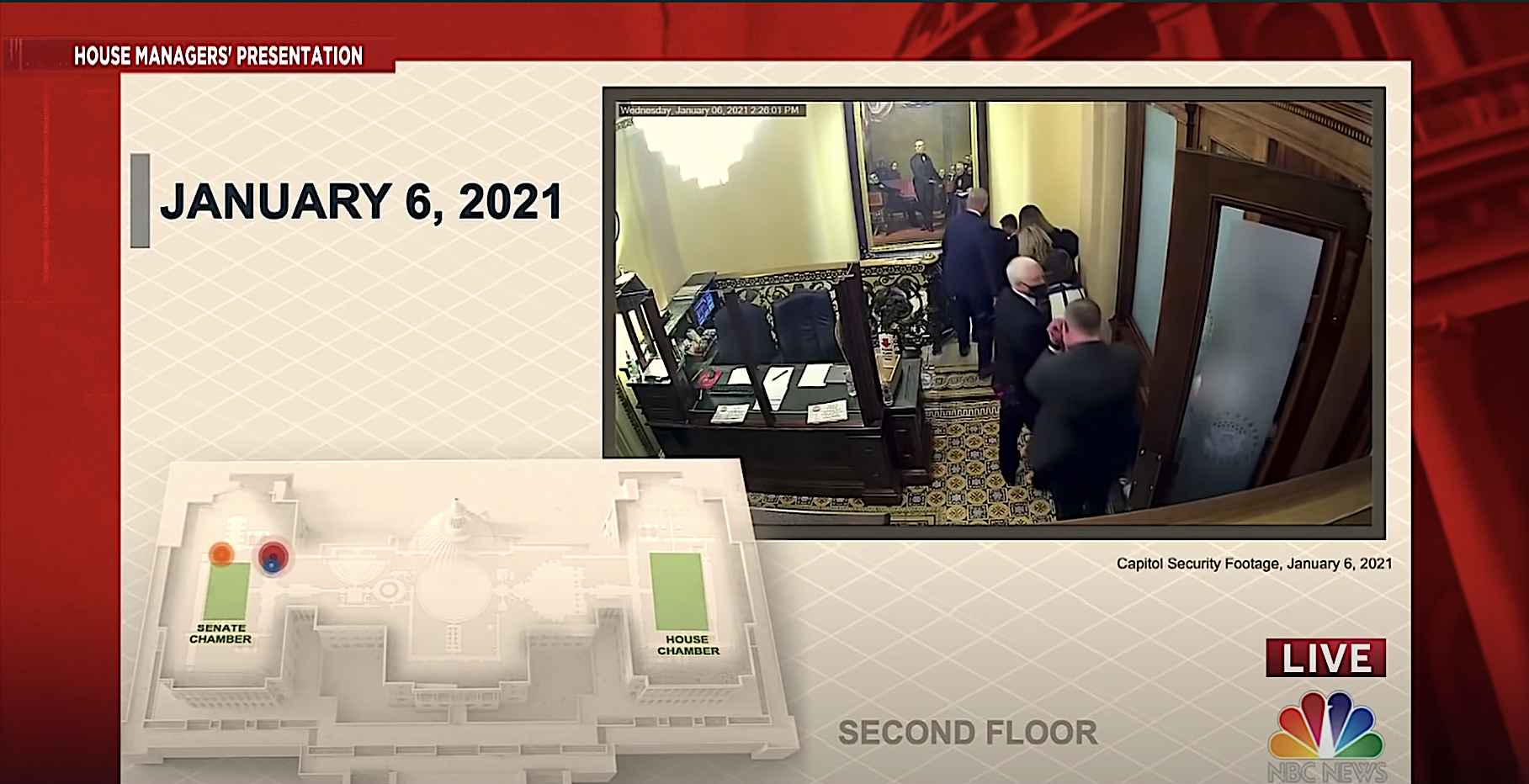

Mike Pence's 'nuclear football' was also apparently at risk during the Capitol siege

Mike Pence's 'nuclear football' was also apparently at risk during the Capitol siegeSpeed Read

-

Trump publicly attacked Pence during the Capitol riot knowing Pence was in trouble, GOP senator suggests

Trump publicly attacked Pence during the Capitol riot knowing Pence was in trouble, GOP senator suggestsSpeed Read