Meet the real villain in the public pension crisis

Hint: It's not greedy firefighters...

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Over the last year, the city of Memphis, Tennessee, has been bleeding firefighters and police officers. Two hundred and fifty of them quit, others retired, and replacements are becoming more difficult to attract. This past July, just over half the city’s police force took a sick day in protest.

Their complaint? A December decision by the City Council to partially move public employee's pensions to a hybrid system that includes 401(k)-style accounts for workers with 7.5 years of tenure or less.

Memphis is not unique in this regard; over the last few years, political and legal battles over public employee pensions have erupted in cities and states alike, including New Jersey, Illinois, Rhode Island, Louisiana, and Detroit. But Memphis stands out for the ferocity with which everyday working Americans have responded to the changes. And it serves as a microcosm for the ways those workers are paying the price for the sins of the American economic elite.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

The way most public pension plans work is that a certain portion of an employee's wages are diverted into an investment portfolio — pooling many workers into one pot — and they're promised a certain level of income from that portfolio in retirement. When people say these pensions — called defined-benefit plans — face a funding shortfall, what they mean is the combined value of the investments plus their expected returns will not cover all the obligations the public employer in question will owe to retirees over a 30-year time horizon.

The alternative — called defined-contribution plans — simply obligates a certain contribution into the portfolio, and the employees get what they get out of it depending on how the portfolio performs.

Defined-benefit plans were actually common in the private sector up through the 1970s. But since then there’s been a massive shift to the defined-contribution package — such as the ubiquitous 401(k)s — in the private sector, and the current city and state fights are over efforts to move public employee pensions in the same direction.

Critics of the defined-benefit plans often assert this is necessary because governments use the more generous packages as cover for fiscally deceptive political games, promising workers future benefits while not properly funding the plans and instead spending the money in the here and now.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

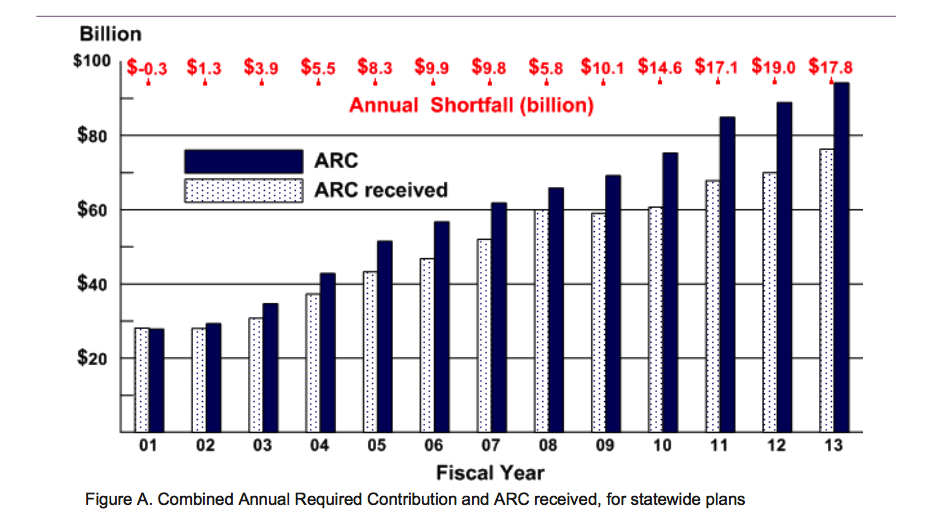

This argument is largely bogus. The National Association of State Retirement Administrators (NASRA) recently looked at the management of 112 state-administered pension funds from 2001 to 2013. They found the plans received an average of 89 percent of their required annual contributions, and only six states — New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Washington, North Dakota, Kansas, and Colorado — averaged less than 75 percent. Half the plans got 95 percent of the needed amount.

"There is a perception that many plans and states have failed, when in fact it's only a handful of states," Keith Brainard, NASRA’s research director, told Business Insurance. With the exception of a handful of outliers, "most states have made a reasonably good effort."

A 2011 study by the Center for Economic and Policy Research (CEPR) came to the same conclusion. What went wrong, in a nutshell, was the 2008 financial crisis. The plans NASRA looked at were just beginning to close a modest gap opened up by the 2001 recession, plus some changes to benefits, when the latest crash expanded the combined shortfall of all the plans from $5.8 billion in 2008 to $17.8 billion in 2013. It hit a nadir at $19 billion in 2012.

In Memphis specifically, the 2008 collapse blew a big hole in the city's pension investment. It went from a surplus — 104.5 percent of the needed assets — to just 79.8 percent. Keep in mind that, like many public employees throughout the country, Memphis' workers don't get Social Security. Their pension plans will likely be their only lifeline in their later years. And firefighters and cops in particular tend to retire early, given the stresses of their jobs.

Frankly, outside the impacts of the recession, these shortfalls are not that big a deal. It's a gap that needs to be closed over the course of 30 years. As of 2014, the money that would be needed to plug the total hole amounted to just 0.2 percent of the economic output the states are expected to generate over that time stretch, and 2 percent of expected tax revenue.

"We don’t tax people today to pre-fund schools or the fire department," Dean Baker, the co-director of CEPR, pointed out to The Nation's Chris Hayes in 2011. "We generally think you want to pay for services as they go."

And that's before you consider that the accounting methodologies often used to assess public pensions inappropriately downplay how much the investments are likely to return.

The money is there if we're willing to use it, but we're not. Teachers, firefighter, police officers, and other public employees are expected to eat cuts to their retirement security, as their employers renege on contractual promises. Even though, when you look at total compensation — wages and benefits — public sector employees arguably make less than private sector workers with comparable skills and experience. And they're expected to eat this cut because of the 2008 financial crisis — an epic act of regulatory, economic, and financial negligence by elites whose retirement will never be in jeopardy.

"I can’t justify me putting my life on the line, and not knowing if my family would be taken care of," Joseph Vaughn, a 35-year-old Memphis native and a firefighter, told the Wall Street Journal. His pension would be altered to the new hybrid form in 2016, so he quit his hometown department to take a job in neighboring Alabama. The pay is less, but it's a defined-benefit plan.

In practical terms, this is all a lesson in the dangers of over-reliance on the stock market to provide for people in retirement. And it highlights the rather unique difficulties states and localities face, but the federal government does not, when it comes to providing public services and spending.

But it's also a moral lesson in who matters to our political and economic systems, and who doesn't.

Jeff Spross was the economics and business correspondent at TheWeek.com. He was previously a reporter at ThinkProgress.

-

Why is the Trump administration talking about ‘Western civilization’?

Why is the Trump administration talking about ‘Western civilization’?Talking Points Rubio says Europe, US bonded by religion and ancestry

-

Quentin Deranque: a student’s death energizes the French far right

Quentin Deranque: a student’s death energizes the French far rightIN THE SPOTLIGHT Reactions to the violent killing of an ultraconservative activist offer a glimpse at the culture wars roiling France ahead of next year’s elections

-

Secured vs. unsecured loans: how do they differ and which is better?

Secured vs. unsecured loans: how do they differ and which is better?the explainer They are distinguished by the level of risk and the inclusion of collateral