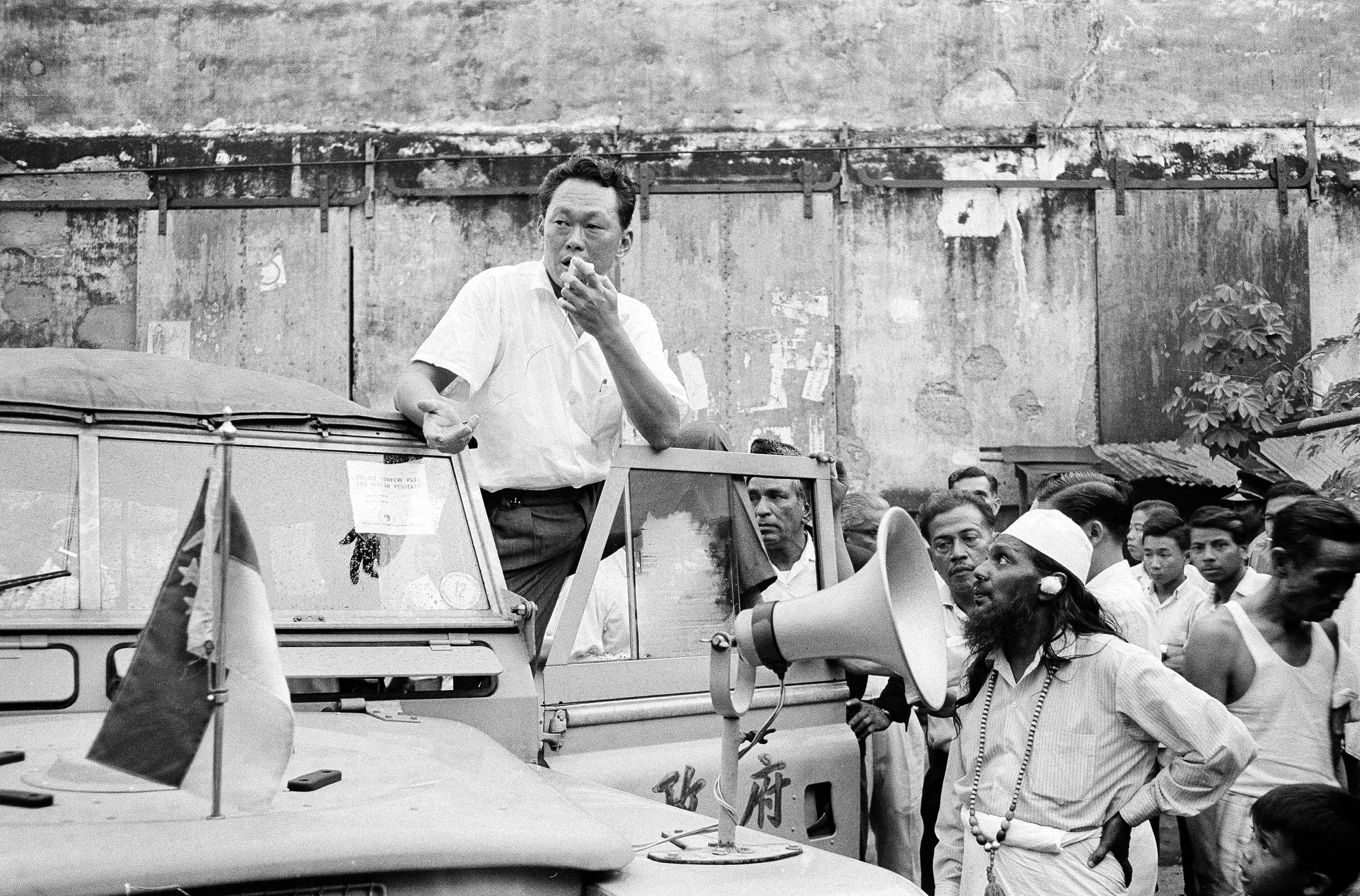

The man who built the modern city-state

Lee Kuan Yew's greatest legacy might not be Singapore itself, but the idea behind it

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Lee Kuan Yew, Singapore's first prime minister and by all accounts the true founder of independent Singapore and the creator of its unique regime, has died at 91.

The outlines of his legacy are easy to draw.

Singapore is, from many perspectives, clearly one of the most successful polities on the planet. The once very poor colony has become one of the wealthiest commonwealths on the planet. It has achieved an astonishing degree of prosperity, social cohesion, and comity. It is almost certainly the most successful welfare state on the planet: able to protect the poor and the middle class while keeping taxes low, all run by one of the world's most famously efficient technocracies. While Singapore's strategic location in the midst of the world's most important shipping lane clearly aided its success, there is also no one who doubts that most of its prosperity is due to the amazing, difference-making work of Lee and his governing agenda. There are dozens of former colonies with great inherent assets, but only one Singapore.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

On the other hand, the criticisms of Singapore are well known. It can seem like The Prisoner's island, only with more boring architecture. Famously, there are steep — and enforced — fines on spitting gum; caning and hanging are in use as legal punishments. There is an inherent creepiness to Singapore's fussy technocratic management, a creep factor that is only enhanced by how efficient and smiley it all is. Singapore is not a dictatorship, exactly, but neither is it a full democracy. There are restrictions on free speech and human rights. While no one doubts that Lee's People Action Party, which has ruled Singapore continuously since its independence, is broadly popular, the electoral system is skewed to maintain its majority.

Lee has defended his regime's authoritarian technocratic as in comport with "Asian values," as opposed to the supposed imposition of "Western values" of democracy which, he claimed, could not work in Asia. It is thought that he has had a bad influence on world politics, by lending credibility to the idea that an authoritarian regime can maintain legitimacy and popularity as long as it delivers the technocratic goods. China's leadership, to take the most obvious example, clearly takes this tack: Far from seeing a progressive shift towards democracy as an either inevitable or desirable follow-up to economic liberalization, it wants to build a Singapore-like state where the party elite remains safely in power. Another obvious emulator of Lee is Paul Kagame's Rwanda, with its creepily clean streets and increasingly iron-gloved authoritarianism. From this vantage point, no matter Singapore's prosperity, Lee's influence on the world has been mostly meretricious, by giving the world's dictators a playbook on how to subtly smother democratic change.

I don't want to settle that debate here. My sense is that the "Asian values" stuff is mostly rhetoric, and that Singapore is headed in the direction of liberalization. And China's corrupt, self-dealing elite would have seen democratic accountability with horror with or without Lee's legacy. At some point, there will be peaceful democratic change in Singapore, and what will shock everyone is how effortless it will be.

What is so striking about Singapore is simply the fact that it exists. The Westphalian order of post-Renaissance Europe gradually squelched one of the most important and valuable forms of polity that existed: the city-state. The great prosperity — and cultural achievements — of the Renaissance were largely midwifed by city-states like Florence and Venice. I like to define a bureaucracy as an organization that does not understand itself to be under competitive pressure. States are always competing with each other — for investment, for growth, for attractiveness. A relatively large state — like, say, California or France — can afford a very long bureaucratic twilight, for even as it bleeds its most talented people, it can stay pain-free for a long time. A city state can ill afford that. Lee's obsession with Singapore's international competitiveness bordered on paranoia. It's no coincidence that Singapore is often contrasted with Hong Kong, another astonishingly successful city state. The world is an astonishingly diverse place, and it is good for all of us when we have astonishingly diverse regimes. I wouldn't want the whole world to be a giant Singapore, but I am in the end glad that Singapore exists as Singapore. We need more Singapores, more Hong Kongs — more Venices and Florence.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

One of the most exciting new movements for global development is the Charter Cities movement which seeks to build Hong Kong-like and Singapore-like efficient city states in the poorest areas in the world. Think of how the existence of Hong Kong amidst Chinese communism's privation not only made millions of people better off, but eventually spurred China's leadership to apply a smattering of Hong Kong-like reforms at home.

If the Charter Cities movement does take off, it might be Lee's greatest, albeit quite involuntary, legacy.

Pascal-Emmanuel Gobry is a writer and fellow at the Ethics and Public Policy Center. His writing has appeared at Forbes, The Atlantic, First Things, Commentary Magazine, The Daily Beast, The Federalist, Quartz, and other places. He lives in Paris with his beloved wife and daughter.

-

Health insurance: Premiums soar as ACA subsidies end

Health insurance: Premiums soar as ACA subsidies endFeature 1.4 million people have dropped coverage

-

Anthropic: AI triggers the ‘SaaSpocalypse’

Anthropic: AI triggers the ‘SaaSpocalypse’Feature A grim reaper for software services?

-

NIH director Bhattacharya tapped as acting CDC head

NIH director Bhattacharya tapped as acting CDC headSpeed Read Jay Bhattacharya, a critic of the CDC’s Covid-19 response, will now lead the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

-

Why Puerto Rico is starving

Why Puerto Rico is starvingThe Explainer Thanks to poor policy design, congressional dithering, and a hostile White House, hundreds of thousands of the most vulnerable Puerto Ricans are about to go hungry

-

Why on Earth does the Olympics still refer to hundreds of athletes as 'ladies'?

Why on Earth does the Olympics still refer to hundreds of athletes as 'ladies'?The Explainer Stop it. Just stop.

-

How to ride out the apocalypse in a big city

How to ride out the apocalypse in a big cityThe Explainer So you live in a city and don't want to die a fiery death ...

-

Puerto Rico, lost in limbo

Puerto Rico, lost in limboThe Explainer Puerto Ricans are Americans, but have a vague legal status that will impair the island's recovery

-

American barbarism

American barbarismThe Explainer What the Las Vegas massacre reveals about the veneer of our civilization

-

Welfare's customer service problem

Welfare's customer service problemThe Explainer Its intentionally mean bureaucracy is crushing poor Americans

-

Nothing about 'blood and soil' is American

Nothing about 'blood and soil' is AmericanThe Explainer Here's what the vile neo-Nazi slogan really means

-

Don't let cell phones ruin America's national parks

Don't let cell phones ruin America's national parksThe Explainer As John Muir wrote, "Only by going alone in silence ... can one truly get into the heart of the wilderness"