Homo floresiensis: Earth’s real-life ‘hobbits’

New research suggests that ‘early human pioneers’ in Australia interbred with archaic species of hobbits at least 60,000 years ago

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

“Experts have long debated the date that humans arrived in Australia,” said LiveScience. Now a study using DNA from both ancient and modern Aboriginal people across Oceania may have finally “settled the debate”.

The study, published last week in Science Advances, looked at an “unprecedentedly large” dataset of nearly 2,500 genomes to determine that humans began to settle northern Australia about 60,000 years ago.

But “even more interestingly”, the study also added to growing evidence that along the way these “early human pioneers likely interbred with archaic humans”, including the species known as “the hobbit”, Homo floresiensis.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Human hobbits

Homo floresiensis “might have been slight in stature”, at just over a metre tall, but its origins have “attracted lengthy debate”, said the Natural History Museum.

At the start of the millennium, most paleoanthropologists believed Homo sapiens was the only human species that had managed to reach Sahul, an ancient landmass that includes modern-day Australia. “It seemed very unlikely that archaic humans had watercraft capable of crossing the ocean.”

But the discovery of Homo floresiensis in 2003 “changed things dramatically”. A team uncovered more than 100 fossils in a cave on “a remote Indonesian island” called Flores, including the partial skeleton of a female: still the most complete Homo floresiensis fossil to date. The adult female was just 1.05 metres tall, earning the species its nickname: the hobbit.

Before the discovery, anthropologists had “assumed that the evolution of the human lineage was defined by bigger and bigger brains”, said anthropology professors Tesla Monson and Andrew Weitz on The Conversation. This, they believed, enabled early modern humans to perform “more complex tasks such as using fire, forging and wielding tools”. The discovery of the hobbits, with their “chimp-sized brain”, forced scientists to throw these theories “out the window”.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

So how did they get to Flores?

Stone tools found on the Indonesian island of Sulawesi were recently dated between 1.04 million and 1.48 million years old. That makes them “the earliest evidence ever discovered of ancient humans making a sea crossing”, said New Scientist. These could “provide clues” as to how the tiny hobbits made it to nearby Flores.

At least one of the artefacts was a flake that was struck off a larger flake and then trimmed. “This is a very early kind of human intelligence from a species that no longer exists,” said team member Adam Brumm, from Griffith University in Brisbane. “We don’t know what species it was, but this is a human intelligence behind these stone artefacts at the site of Calio.”

Both Flores and Sulawesi were separated from the mainland by “large expanses of sea”, and it is “almost certain that these early hominins weren’t capable of building ocean-going vessels”. The original population might have been washed out to sea by “some sort of freak geological event” such as a tsunami.

But the late archaeologist Mike Morwood, who led the team that originally identified Homo floresiensis, suggested that Sulawesi was “an important place to search for potential ancestors of the hobbits”.

Alex Kerr joined The Week as an intern for four months in 2025, covering global news, arts and culture. A third-year undergraduate student at New York University’s Gallatin School of Individualised Study, Alex studies politics, social justice and the written word. During her time in New York, she was a staff writer for WNYU Radio’s STATIC, a student-led underground music magazine. Her interests include left-wing and American politics, alternative music and culinary journalism. After graduating, she intends to pursue an MSc in political theory.

-

Will increasing tensions with Iran boil over into war?

Will increasing tensions with Iran boil over into war?Today’s Big Question President Donald Trump has recently been threatening the country

-

Corruption: The spy sheikh and the president

Corruption: The spy sheikh and the presidentFeature Trump is at the center of another scandal

-

Putin’s shadow war

Putin’s shadow warFeature The Kremlin is waging a campaign of sabotage and subversion against Ukraine’s allies in the West

-

The curious history of hanging coffins

The curious history of hanging coffinsUnder The Radar Ancient societies in southern China pegged coffins into high cliffsides in burial ritual linked to good fortune

-

Mendik Tepe: the ancient site rewriting human history

Mendik Tepe: the ancient site rewriting human historyUnder The Radar Excavations of Neolithic site in Turkey suggest human settlements more than 12,000 years ago

-

The seven strangest historical discoveries made in 2025

The seven strangest historical discoveries made in 2025The Explainer From prehistoric sunscreen to a brain that turned to glass, we've learned some surprising new facts about human history

-

Argentina lifts veil on its past as a refuge for Nazis

Argentina lifts veil on its past as a refuge for NazisUnder the Radar President Javier Milei publishes documents detailing country's role as post-WW2 'haven' for Nazis, including Josef Mengele and Adolf Eichmann

-

Scientists have found the first proof that ancient humans fought animals

Scientists have found the first proof that ancient humans fought animalsUnder the Radar A human skeleton definitively shows damage from a lion's bite

-

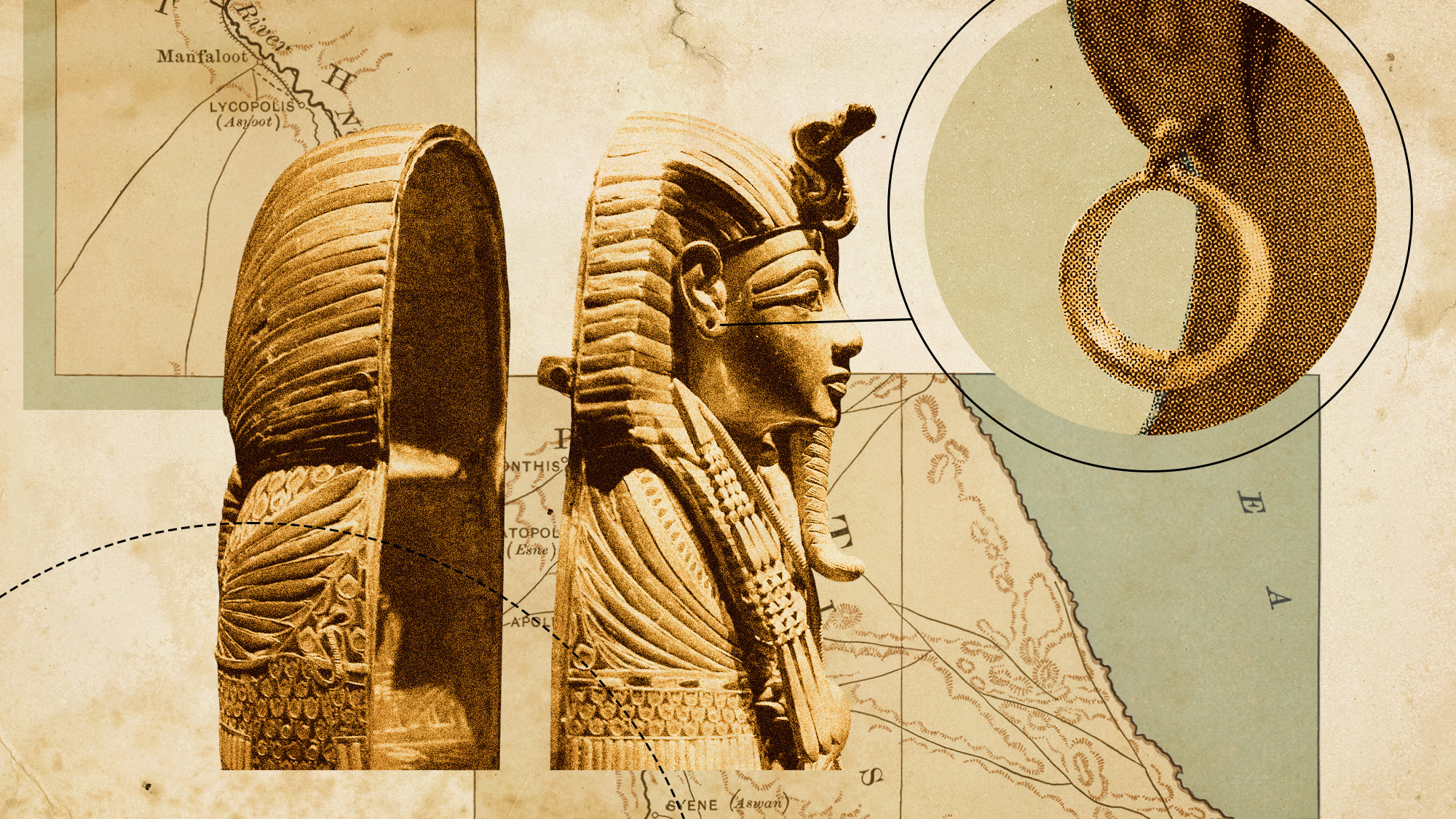

Tutankhamun: the mystery of the boy pharaoh's pierced ears

Tutankhamun: the mystery of the boy pharaoh's pierced earsUnder the Radar Researchers believe piercings suggest the iconic funerary mask may have been intended for a woman

-

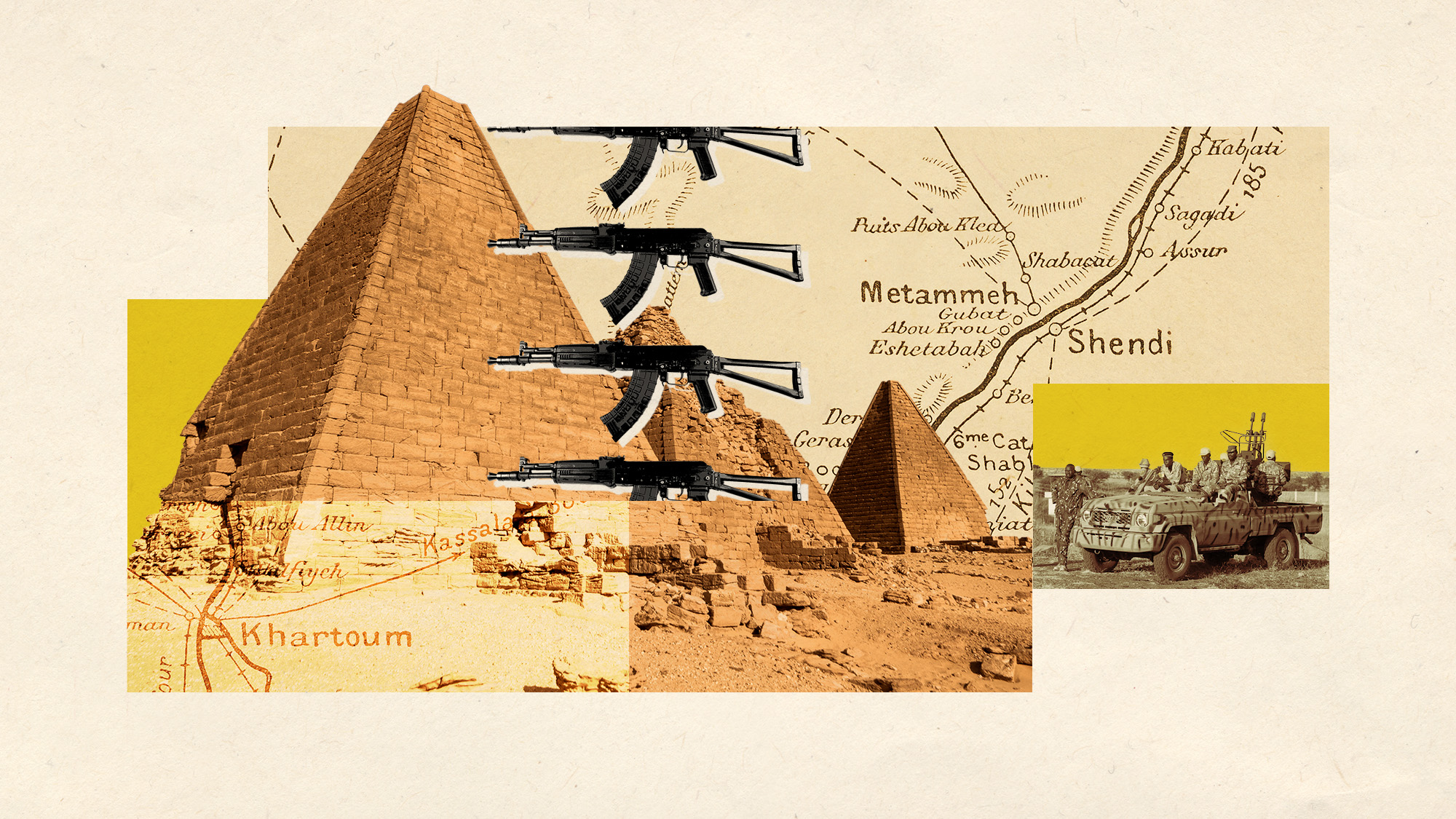

Sudan's forgotten pyramids

Sudan's forgotten pyramidsUnder the Radar Brutal civil war and widespread looting threatens African nation's ancient heritage

-

All about Zealandia, the Earth's potential 8th continent

All about Zealandia, the Earth's potential 8th continentThe Explainer The secret continent went undiscovered for over 300 years