Making sense of a tragedy at sea

It is hard not to feel that the capsizing of the migrant ship is tragic in its proper, Greek sense: tragic because it was inevitable

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Last Sunday, a ship crowded with migrants capsized and sank in the middle of the Mediterranean. As many as 900 are feared dead. The details are as grisly as one might surmise: While some bodies have been seen floating in the water, apparently most of those who died — packed into the ship like sardines — were trapped in a locked hold of the boat.

This is part of a steady drip, drip of such enormously depressing news. According to humanitarian groups, already 1,727 migrants have died at sea this year. Critics say that the EU's program to rescue migrants lost at sea is underfunded and skeletal — and the EU evidently agrees, having put forward a plan to extend it in an emergency session.

It is hard not to feel that this event is tragic in its proper, Greek sense: tragic because it was inevitable. We all know the socioeconomic and political reasons why desperate migrants go pack themselves on unsafe ships and risk it all to try to make it to the European Union. We know that whatever we — the rich in the peaceful West — do, they will keep trying. And we know that whether we believe that's a good thing or not, our countries will never stop pushing them away.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

A freak accident can sometimes be more painful because of the shock, but at least we can reassure ourselves by telling ourselves that it is merely an occasional exception to the mostly-good rules of a mostly-good world. Not this. The deeply tragic sense of this event and so many like it reawakens us to the truly shocking reality of the world, this world where children die for no good reason, where people sleep on the streets, where parents abuse children, where war has always been part of existence.

At this point, one may reach for the comforts of philosophy or religion.

One may find, as the ancient Indo-European religions did, that this is the true reality of the world: an endless cycle of sacrifice guided by fate, which cares nothing for us but only to maintain the cycle of feeding. One may follow this logic to the best Greek and Roman philosophers or, for that matter, the Buddha, who taught that since this is the meaning of reality, the only way to find serenity is through detachment. Do not let yourself be affected, and you will be fine.

Or one may turn one's eyes to the folly that is the Gospel of Jesus Christ, which proclaims, against all seeming evidence to the contrary, that we live in a good world. And while this world has fallen prey to sin and decay, it is also being rescued by God. In this interpretation, what would seem striking is not that migrants die, but that we somehow feel this is unjust, as if we were born with a standard for justice much higher than anything we encounter in this world. As if we were destined for infinite truth, goodness and beauty, not the quick death of advanced primates.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

We might be moved to all these idle thoughts. Or we might be moved by simple compassion. Can the Western world take in all the world's migrants? Maybe not. Or maybe so. But that's besides the point. What is certain is that we can take more, and we have a duty to do so.

While there is a good argument that large-scale immigration of moderately-skilled workers undermines a country's economy and social cohesion, this is not the case for migrants from the world's poorest countries. While moderately-skilled immigrants sometimes do replace those from the country's already existing (and, because of globalization and other trends, fragile) working class, poor migrants from poor countries typically take the jobs no one else wants. And people don't get on boats like this if they're not willing to work hard once they get to their destination.

I don't know what's the maximum number of immigrants from the poorest parts of the world we can take in. But I sure want to find out.

Pascal-Emmanuel Gobry is a writer and fellow at the Ethics and Public Policy Center. His writing has appeared at Forbes, The Atlantic, First Things, Commentary Magazine, The Daily Beast, The Federalist, Quartz, and other places. He lives in Paris with his beloved wife and daughter.

-

The week’s best photos

The week’s best photosIn Pictures An explosive meal, a carnival of joy, and more

-

The ‘ravenous’ demand for Cornish minerals

The ‘ravenous’ demand for Cornish mineralsUnder the Radar Growing need for critical minerals to power tech has intensified ‘appetite’ for lithium, which could be a ‘huge boon’ for local economy

-

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?IN THE SPOTLIGHT As the president muses about polling place deployments and a centralized electoral system aimed at one-party control, lawmakers are taking this administration at its word

-

'Once the best in the Middle East,' Beirut hospital pleads for fuel as it faces shutdown

'Once the best in the Middle East,' Beirut hospital pleads for fuel as it faces shutdownSpeed Read

-

Israeli airstrikes kill senior Hamas figures

Israeli airstrikes kill senior Hamas figuresSpeed Read

-

An anti-vax conspiracy theory is apparently making anti-maskers consider masking up, social distancing

An anti-vax conspiracy theory is apparently making anti-maskers consider masking up, social distancingSpeed Read

-

Fighting between Israel and Hamas intensifies, with dozens dead

Fighting between Israel and Hamas intensifies, with dozens deadSpeed Read

-

United States shares 'serious concerns' with Israel over planned evictions

United States shares 'serious concerns' with Israel over planned evictionsSpeed Read

-

Police raid in Rio de Janeiro favela leaves at least 25 dead

Police raid in Rio de Janeiro favela leaves at least 25 deadSpeed Read

-

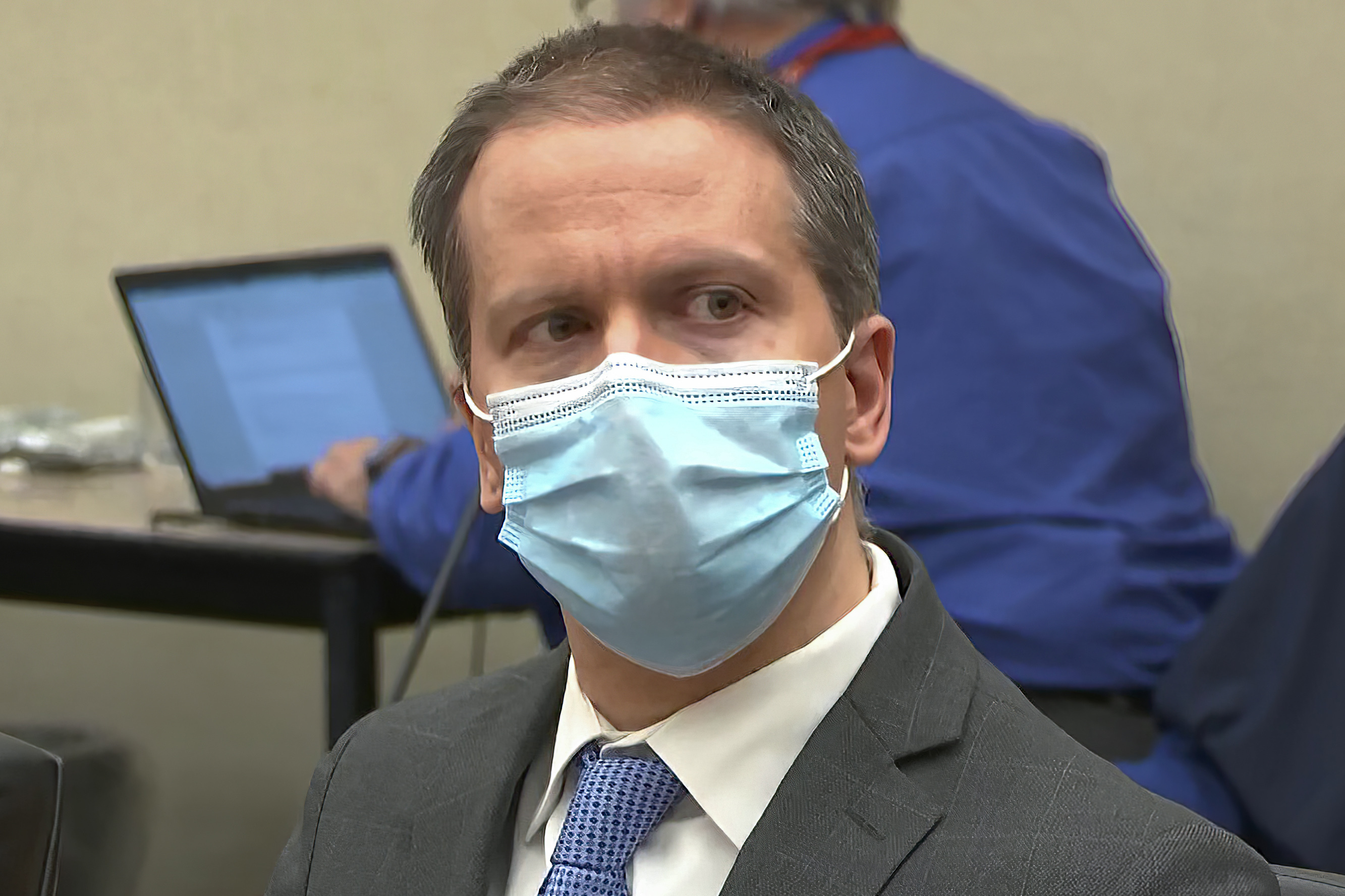

Derek Chauvin's attorney files motion for new trial

Derek Chauvin's attorney files motion for new trialSpeed Read

-

At least 20 dead after Mexico City commuter train splits in overpass collapse

At least 20 dead after Mexico City commuter train splits in overpass collapseSpeed Read