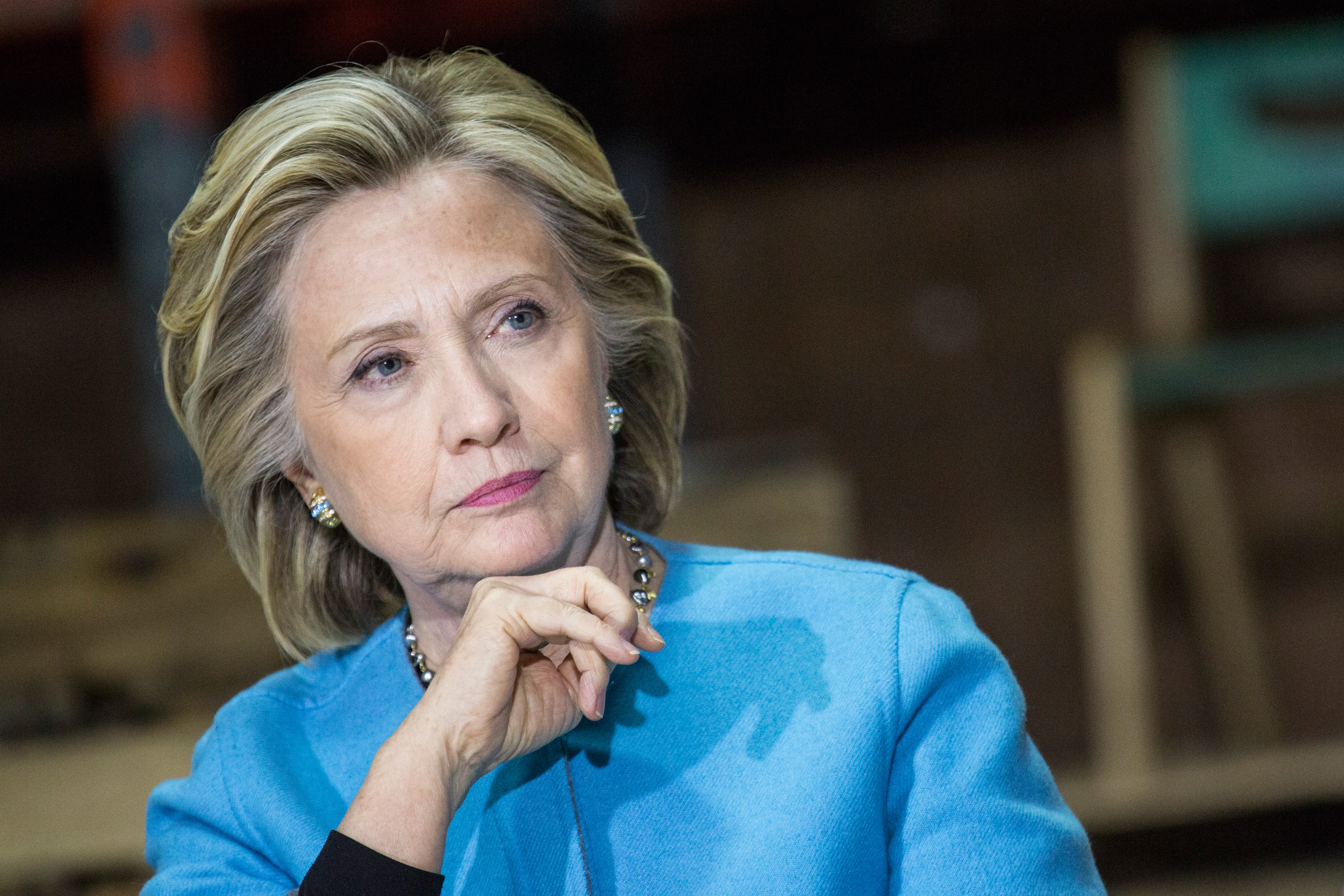

Hillary Clinton and the soft corruption of low expectations

There's no smoking gun of a Clinton Foundation quid pro quo. But since when is that the standard for investigation?

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

George W. Bush often spoke about the disparities in how the government treated different groups of people, especially students that our system assumed could never succeed. These students, Bush said, suffered from "the soft bigotry of low expectations."

Well, in this election cycle, the American body politic has been afflicted with the soft corruption of low expectations — and it's getting worse.

Take, for instance, the reaction to the revelations about the Clinton Foundation, its potential financial connections to business conducted by the State Department, and the personal enrichment of Bill Clinton by that nexus. Author Peter Schweizer details a number of these "coincidences" in his book Clinton Cash, but the gravest so far concern the sale of uranium assets to Russian interests.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Schweizer notes that the former president's speaking fees skyrocketed when Hillary Clinton became secretary of state. Eleven of his $500,000-per-speech paydays came after 2009, during her tenure at the State Department, including one in Russia for a speech funded by an investment bank with ties to Vladimir Putin. The New York Times' Jo Becker and Mike McIntire reported that the bank paying for Bill Clinton's half-million-dollar speech also backed the acquisition of Uranium One by Rosatom, a Russian energy group with ties to Putin. At the same time, the Clinton Foundation received millions from Uranium One's owners, while the State Department under Hillary Clinton approved the sale that enriched everyone. The deal gives the Russian government control over half of the world's supply of uranium — a perfect position for Putin, which has sold nuclear technology to Iran.

The foundation itself isn't exactly aces, either. A study of foundation tax records by The Federalist showed that only 15 percent of its revenue between 2009 and 2012 went to direct grants to charitable works. In 2013, after Hillary Clinton left the State Department and began to work on a presidential campaign, the number dropped to a 6.4 percent, giving out just $9 million from revenues of $140 million, and spending almost the same amount on travel expenses alone. Charity Navigator put the Clinton Foundation on its watch list, and the Sunlight Foundation's Bill Allison bluntly stated, "It seems like the Clinton Foundation operates as a slush fund for the Clintons."

You might expect the national media to press the Clintons for answers. And many — like The New York Times — are. Others, however, seem more determined to demand answers from Schweizer.

For instance, ABC's George Stephanopoulos argued that Schweizer hadn't provided "proof of any kind of direct action." Schweizer responded by providing an analogy to insider trading. The SEC would certainly take an interest in such a confluence of money and regulatory approvals on a sale that benefited the people putting millions of dollars into a corporation the way the Rosatom deal did with the Clinton Foundation — and a cool half-million into a family member's pockets, no less.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

All of this came from public tax and corporate records, Schweizer noted. An investigation by relevant authorities with the power to compel disclosures of privately held records is needed to establish any potential quid pro quo. Stephanopoulos, who once worked in the Clinton White House, shrugged it off by saying that Schweizer's reports "haven't confirmed any evidence of any crime."

That's a strange standard for the media to take when it comes to potential corruption. Imagine Woodward and Bernstein telling their sources on Watergate, Eh, come back when you have an indictment and we'll talk.

International Business Times' David Sirota expressed astonishment at the sudden silence from Democrats:

Ron Fournier laments that the "no evidence" standard is the Clinton team's only answer. "Clinton's crisis management team makes a big deal of the fact that Clinton Cash author Peter Schweizer hasn't proven a "quid pro quo," Fournier notes. "Really? It takes a pretty desperate and cynical campaign to set the bar of acceptable behavior at anything short of bribery."

The low bar extends to the campaign itself. In a very real sense, Hillary Clinton has prepared for a presidential campaign since 2000. Every move since — running for the U.S. Senate, the first memoir, and the Clinton Foundation itself — was designed to propel her to the White House in 2008. Her term as secretary of state and the second memoir was designed for the 2016 campaign. And yet Hillary Clinton has yet to articulate why she's running for president. She penned an op-ed for the Des Moines Register this week filled with platitudes but saying nothing about her plans to govern. Over the two weeks since she announced her candidacy, she's taken a grand total of seven questions from the press.

The Hillary Clinton campaign is the epitome of the soft corruption of low expectations. By refusing to hold her to a higher standard, Democrats and the media are in effect endorsing the kind of cronyism the Clinton Foundation and the Clintons themselves represent. We should forget the standards of indictments and smoking guns, and ask ourselves whether the Clintons are really the best America can do for leadership. That's the standard that matters, and the standard that the media at one time claimed to support.

Edward Morrissey has been writing about politics since 2003 in his blog, Captain's Quarters, and now writes for HotAir.com. His columns have appeared in the Washington Post, the New York Post, The New York Sun, the Washington Times, and other newspapers. Morrissey has a daily Internet talk show on politics and culture at Hot Air. Since 2004, Morrissey has had a weekend talk radio show in the Minneapolis/St. Paul area and often fills in as a guest on Salem Radio Network's nationally-syndicated shows. He lives in the Twin Cities area of Minnesota with his wife, son and daughter-in-law, and his two granddaughters. Morrissey's new book, GOING RED, will be published by Crown Forum on April 5, 2016.

-

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

Earth is rapidly approaching a ‘hothouse’ trajectory of warming

Earth is rapidly approaching a ‘hothouse’ trajectory of warmingThe explainer It may become impossible to fix

-

Health insurance: Premiums soar as ACA subsidies end

Health insurance: Premiums soar as ACA subsidies endFeature 1.4 million people have dropped coverage

-

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?Talking Point Peter Thiel and Larry Page preparing to change state residency

-

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one report

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one reportIN THE SPOTLIGHT By blocking an approved segment on a controversial prison holding US deportees in El Salvador, the editor-in-chief of CBS News has become the main story

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June

-

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardon

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardonTalking Point Convicted sex trafficker's testimony could shed new light on president's links to Jeffrey Epstein

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred