Soccer's corrupt soul

American investigators have uncovered a deep-rooted corruption scandal at FIFA, soccer's governing body

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

American investigators have uncovered a deep-rooted corruption scandal at FIFA, soccer's governing body. Here's everything you need to know:

What's being alleged?

Prosecutors say FIFA officials have engaged in "rampant, systemic" corruption over 24 years, essentially selling off the rights to host World Cups and other tournaments for $150 million in bribes and kickbacks. The alleged graft, much of which took place on U.S. soil or through American banks, involved at least 14 FIFA officials; some of the payoffs were hidden in complex financial arrangements, while others were made in cash-stuffed briefcases. "They did this over and over," said U.S. Attorney General Loretta Lynch. "Year after year, tournament after tournament." The scandal has already forced the resignation of the previously untouchable FIFA president, Sepp Blatter, and prompted police in Switzerland, where the organization is based, to launch an investigation into "irregularities" over the awarding of the 2018 and 2022 World Cups to Russia and Qatar.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Why is FIFA so corrupt?

Hosting rights for the World Cup are extremely valuable, providing the winning country with great prestige and billions in development and spending. Every four years, a host nation is chosen in a vote by 24 senior FIFA officials, giving a handful of individuals enormous leverage over the bidders. Bribes and kickbacks naturally follow, especially since in many of the competing nations, paying off powerful officials is commonplace. These same FIFA bigwigs are also responsible for dishing out media rights for regional tournaments — another golden opportunity to have their palms greased.

Why did the U.S. get involved?

The turning point came on December 2, 2010, with the shocking announcement that the 2022 World Cup would be held in Qatar. A Persian Gulf state the size of Connecticut, Qatar has no soccer tradition, and summer temperatures average about 113 degrees — hardly ideal for a sport in which players run almost constantly. The organizers' pledge to build air-conditioned stadiums predictably proved far-fetched, so the tournament was moved to winter — right in the middle of Europe's professional-league seasons. Almost all of Qatar's requisite hotels, stadiums, and other infrastructure are being built from scratch by South Asian immigrants who are essentially slave labor. Working 12-hour days and housed in filthy, overcrowded hostels, these workers are unable to leave their jobs or the country without an "exit permit." Hundreds are believed to have died from heatstroke and in construction-site accidents. For many soccer fans, the Qatar 2022 decision was one corrupt step too far. For the U.S., which finished second in the bidding process, it was personal.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

What did the U.S. do?

Federal investigators started looking into the regional FIFA confederation, covering the Caribbean and North and Central America — and quickly discovered widespread, ingrained corruption. At the heart of the graft was Chuck Blazer, a bushy-bearded, 450-pound American who had worked his way up from low-level soccer administration to the upper echelons of the FIFA oligarchy. Known as "Mr. 10 Percent," Blazer made a fortune taking a cut from lucrative media contracts he secured for regional tournaments — and spent another fortune on expenses, food, and wine. He billed FIFA $24,000 a month for two apartments in New York's Trump Tower — one for him, one for his office and pet cats — and racked up $29 million over seven years on his corporate credit card. Blazer's downfall, though, was that he didn't pay his taxes. In 2011, he was confronted by FBI and IRS agents as he drove one of his mobility scooters up Fifth Avenue in Manhattan. "We can take you away in handcuffs now," they told him, "or you can cooperate."

What did he do?

Facing years in prison for tax evasion, Blazer became an informer. He admitted receiving bribes for the 1998 and 2010 World Cup bids, and secretly recorded crooked colleagues with a microphone hidden in a key fob. That helped uncover a cesspool of corruption that went back years. Ahead of the bidding process for the 2010 World Cup, for example, Morocco allegedly offered Blazer's superior and long-time confidant, Jack Warner, $1 million for his vote — only to be trumped by a $10 million bribe from eventual winner South Africa. Blazer has since ratted on Warner, who in turn has promised to produce "an avalanche" of revelations about corruption within FIFA.

Can FIFA clean itself up?

That would seem unlikely. One of the favorites to succeed Blatter is Frenchman Michel Platini, a long-time FIFA power broker who voted for Qatar's bid. A British newspaper has accused Platini of receiving a Picasso from Vladimir Putin in return for supporting Russia 2018. (Platini has fiercely denied the Picasso story.) No matter who succeeds Blatter, many of the organization's smaller nations will want to preserve the status quo, because FIFA officials have showered them with funding to secure their support in elections. Much of this money is pocketed, legally and illegally, by the same local soccer officials who will vote on FIFA reforms. Nevertheless, there is hope within "the beautiful game" that the indictments will mark a turning point. "This is the beginning of our effort," said U.S. Attorney Kelly Currie, "not the end."

FIFA's white elephants

Central among FIFA's requirements for World Cup hosts is an emphasis on "legacy." For Qatar 2022, for example, the Persian Gulf state promised to spend an astonishing $200 billion on new stadiums and other infrastructure, and even pledged to dismantle some of the new soccer venues afterward and rebuild them in poorer countries. But as with the Olympics, World Cup legacies often disappoint — as last year's host, Brazil, is now discovering. The country's centerpiece $550 million stadium in capital Brasilia is being used as a parking lot for municipal buses. In the western city of Cuiabá, the newly built stadium was recently inhabited by homeless squatters, and an $800 million light railway to take fans there still hasn't been completed and is running four times over budget. "I don't see any World Cup legacy to Brazil," says Brazilian journalist José Cruz, "except the debts we have inherited and the problems we now have."

-

Political cartoons for February 16

Political cartoons for February 16Cartoons Monday’s political cartoons include President's Day, a valentine from the Epstein files, and more

-

Regent Hong Kong: a tranquil haven with a prime waterfront spot

Regent Hong Kong: a tranquil haven with a prime waterfront spotThe Week Recommends The trendy hotel recently underwent an extensive two-year revamp

-

The problem with diagnosing profound autism

The problem with diagnosing profound autismThe Explainer Experts are reconsidering the idea of autism as a spectrum, which could impact diagnoses and policy making for the condition

-

The hottest Super Bowl ad trend? Not running an ad.

The hottest Super Bowl ad trend? Not running an ad.The Explainer The big game will showcase a variety of savvy — or cynical? — pandemic PR strategies

-

Tom Brady bet on himself. So did Bill Belichick.

Tom Brady bet on himself. So did Bill Belichick.The Explainer How to make sense of the Boston massacre

-

The 13 most exciting moments of Super Bowl LIII

The 13 most exciting moments of Super Bowl LIIIThe Explainer Most boring Super Bowl ... ever?

-

The enduring appeal of Michigan vs. Ohio State

The enduring appeal of Michigan vs. Ohio StateThe Explainer I and millions of other people in these two cold post-industrial states would not miss The Game for anything this side of heaven

-

When sports teams fleece taxpayers

When sports teams fleece taxpayersThe Explainer Do taxpayers benefit from spending billions to subsidize sports stadiums? The data suggests otherwise.

-

The 2018 World Series is bad for baseball

The 2018 World Series is bad for baseballThe Explainer Boston and L.A.? This stinks.

-

This World Series is all about the managers

This World Series is all about the managersThe Explainer Baseball's top minds face off

-

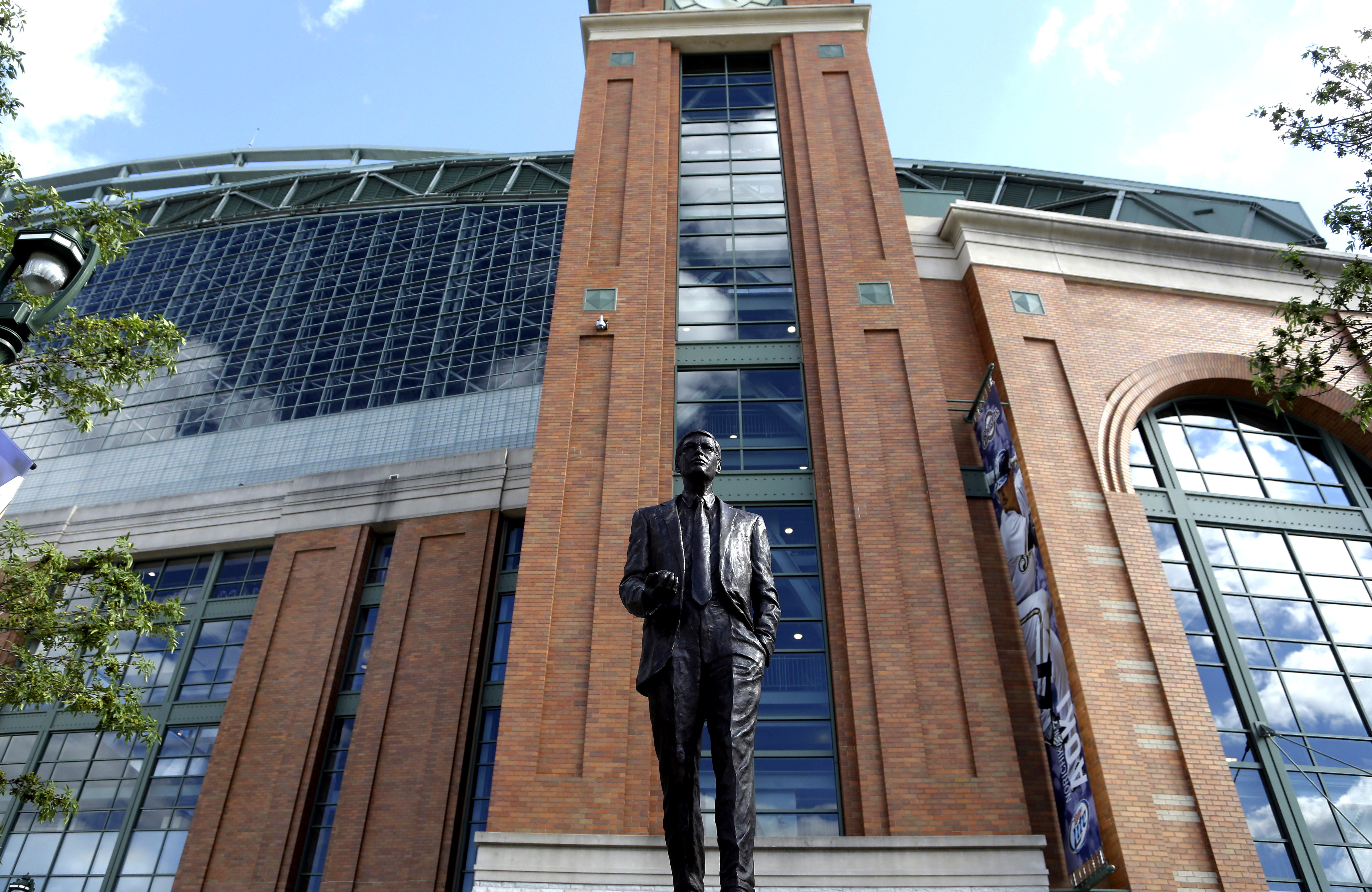

Behold, the Bud Selig experience

Behold, the Bud Selig experienceThe Explainer I visited "The Selig Experience" and all I got was this stupid 3D Bud Selig hologram