American manufacturing jobs are never coming back

The left yearns for an economy that will never return

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

There is a populist wave sweeping America. The progressive economic philosophies of liberal Sens. Elizabeth Warren and Bernie Sanders are resonating, with a big chunk of the voting public seeing progressive populism as a better alternative to the reckless capitalism that many blame for the 2008 financial crash.

But here's the thing: While both senators are lauded as "progressive," they base a lot of their economic philosophy on an idea rooted in yesteryear: the return of American manufacturing.

"We must rebuild American manufacturing and rewrite our trade agreements so that our largest export is not our jobs," reads a Sanders-centric meme on the senator's Facebook page. The seventh item on his "12 Steps Forward" plan to restore the economy points the finger squarely at the loss of American manufacturing.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Warren parrots Sanders' sentiment: "As a senator, I'll work hard to ensure that we make things here in Massachusetts and that we lead the country in bringing manufacturing back to America." Unsurprisingly, restoring America to its factory-based foundation is a major part of her economic plan, too.

These positions are understandable given Warren's and Sanders' Democratic base and the era in which each politician grew up. But it's also wholly unrealistic to expect American manufacturing jobs to bounce back. We can't go back in time.

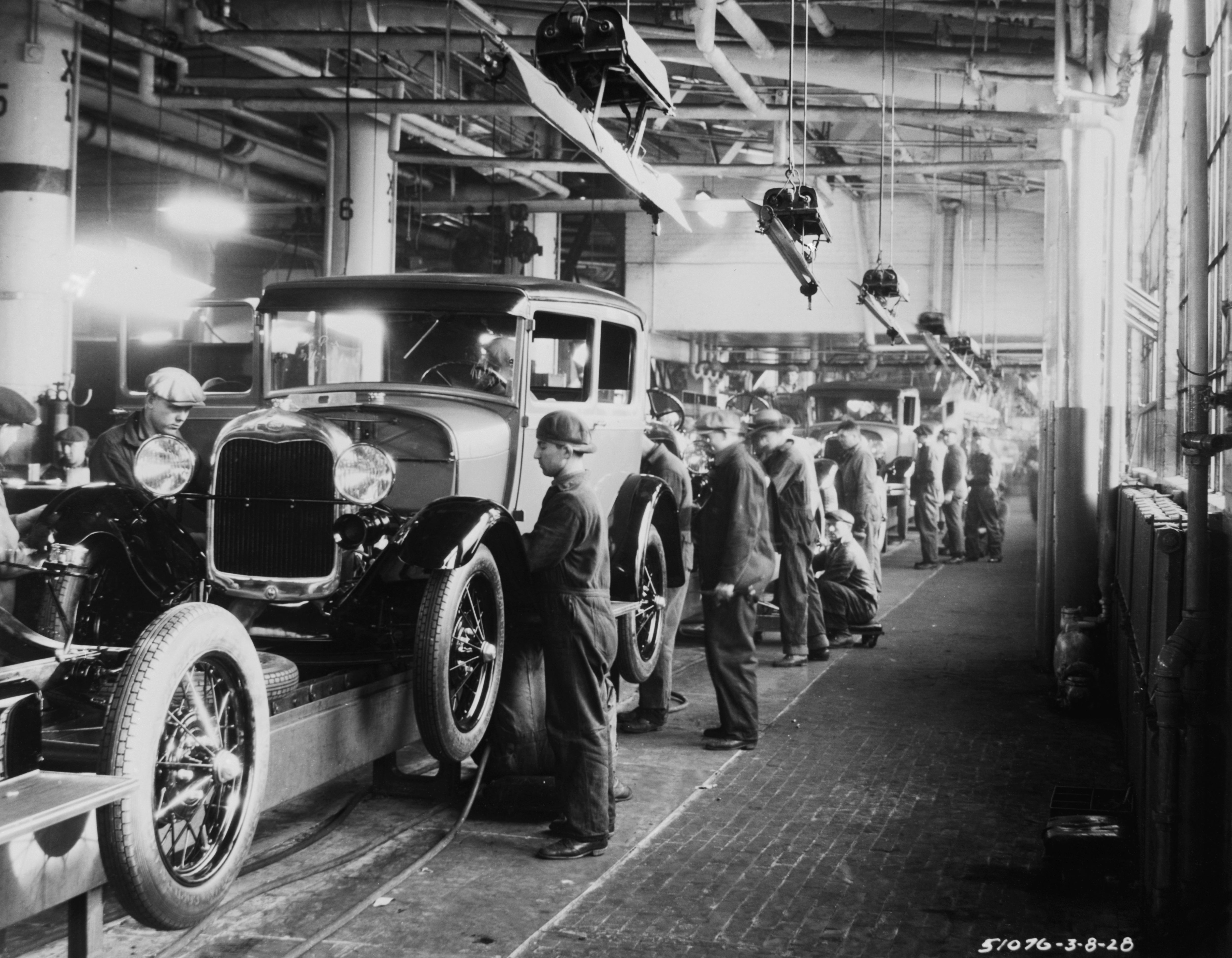

In 1953, at the height of the factory economy, manufacturing accounted for more than 28 percent of America's GDP. By 2009, that number had shrunk to 11 percent. Employment in manufacturing peaked in 1979, when nearly 20 million Americans worked in the sector; today, just over 12 million American jobs fall into the "manufacturing" category.

The return of American manufacturing is a nice idea. It recalls an America in which a hard-working kid could go straight from high school to a steady job in his hometown factory, live a solidly middle-class life, and retire somewhat comfortably at 55 or 60.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

But face it: That America is gone. And no amount of progressive promises will bring it back.

Now, before you point to a recent modest resurgence in domestic manufacturing on the order of thousands of jobs, please consider that the economies of Sanders and Warren require millions. And with automation making inroads every day, it should be very clear that the work that once fueled industrial America will soon be done by machines (2013 was a record year for sales of robots of the industrial variety).

Machines make fewer mistakes, don't take vacations or lunch breaks, and are terrible at asking for raises. There should be little doubt that we have entered an era of automation from which there is no return. A report from Oxford puts the damage at 45 percent of American jobs in two decades, while a study by Boston Consulting Group estimates a 22 percent decline in manufacturing employment by 2025, all thanks to robots.

The robots are here, or will soon be here. And chances are, your job may well become theirs.

That's why manufacturing is simply not a viable, sweeping, long-term solution for the problem of America's shrinking, struggling middle class, no matter how good it sounds on progressives' political posters. There is no undoing technological innovation.

But that's not necessarily a bad thing! America doesn't definitely need manufacturing to thrive. GDP tripled during a drastic reduction in the manufacturing workforce from 1970 to 2010, while population increased by roughly a third. In fact, American GDP increased roughly 20 percent from the end of 2001 to March of 2013, despite a negligible increase in hours worked and jobs created, an increase in productivity brought on largely, if not primarily, by automation in the workplace.

Of course, this meant plenty of pain for millions of workers. That is a very real thing. But only in recognizing the reality of coming innovation and automation can we help future generations hurt less.

There is no denying that at one time factory jobs and the manufacturing sector were critical fuel for America's economic rocket engine. But failing to realize that the world has changed in profound ways, and expressing the naiveté necessary to believe we can turn back the hands of times, is unbecoming of our leaders.

We need to recalibrate our thinking. The good middle-class jobs are or will soon be far removed from assembly lines and the local steelworkers' union. Rather, they will reside in laboratories and software companies. And the dollars will likely fill the pockets of programmers and robotics engineers.

True progress requires planning for the inevitable future: an economy rooted in engineering, information technology, and computer science, not the jobs of yesterday that are never coming back.

And again, that's not necessarily a bad thing. As Ray Kurzweil, famous futurist and director of engineering at Google, points out:

You can point to jobs that are going to go away from automation, but don't worry, we're going to invent new jobs. People say, "What new jobs?" I don't know. They haven't been invented yet. Sixty-five percent of Americans today work at information jobs that didn't exist 25 years ago, two-thirds of the population in 1900 worked either on farms or on factories... We're constantly inventing new things to do with our time, but you can't really define that because the future hasn't been invented yet. [Ray Kurzweil]

But it will be invented. This is progress, and it is coming — whether progressives like it or not.

Greg Jones is a freelance writer who covers technology and politics.

-

ICE’s facial scanning is the tip of the surveillance iceberg

ICE’s facial scanning is the tip of the surveillance icebergIN THE SPOTLIGHT Federal troops are increasingly turning to high-tech tracking tools that push the boundaries of personal privacy

-

‘My donation felt like a rejection of the day’s politics’

‘My donation felt like a rejection of the day’s politics’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

Trump wants a weaker dollar but economists aren’t so sure

Trump wants a weaker dollar but economists aren’t so sureTalking Points A weaker dollar can make imports more expensive but also boost gold

-

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?Talking Point Peter Thiel and Larry Page preparing to change state residency

-

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one report

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one reportIN THE SPOTLIGHT By blocking an approved segment on a controversial prison holding US deportees in El Salvador, the editor-in-chief of CBS News has become the main story

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June

-

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardon

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardonTalking Point Convicted sex trafficker's testimony could shed new light on president's links to Jeffrey Epstein

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred