Don't panic: Why the Chinese economy will (probably) be just fine

Is China headed toward a bust? Or are its troubles part of a larger transition?

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Back in early July, China's stock market rattled the global financial world by taking a nosedive that wiped out a third of its value. But the plunge came after a remarkable run-up in the major Chinese stock indexes, and even after the drop they remained well above their pre-2014 level. The Chinese government also threw the kitchen sink at the problem, and the dive appeared to peter out.

But what it didn't do was reverse the dive. Fast forward to last week, when China's main stock index fell 11.5 percent — to nearly the same low it reached at the depths of the July plunge — freaking out global financial markets all over again.

It's always important to remember that the stock market is not the real economy — the latter being the daily jobs and industries and services and business transactions that make up a society's economic fabric. Disaster in the one doesn't necessarily mean disaster in the other.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

But something different is happening this time around. There's some circumstantial evidence tying the stock markets' drop to real changes in the world's second-largest economy.

In mid-August, worries about sluggish domestic demand and a stalled real estate market convinced China's central bank to create more money, aimed at devaluing the yuan, or renminbi, by 2 percent against the U.S. dollar. Chinese exports to the rest of the world dropped 8.3 percent in July, and American businesses also noted a slowdown of sales in the country. Two big explosions just over a week ago, in a major Chinese port city, certainly didn't help matters either, exposing the corrupt ties between government and business that underlie China's economy.

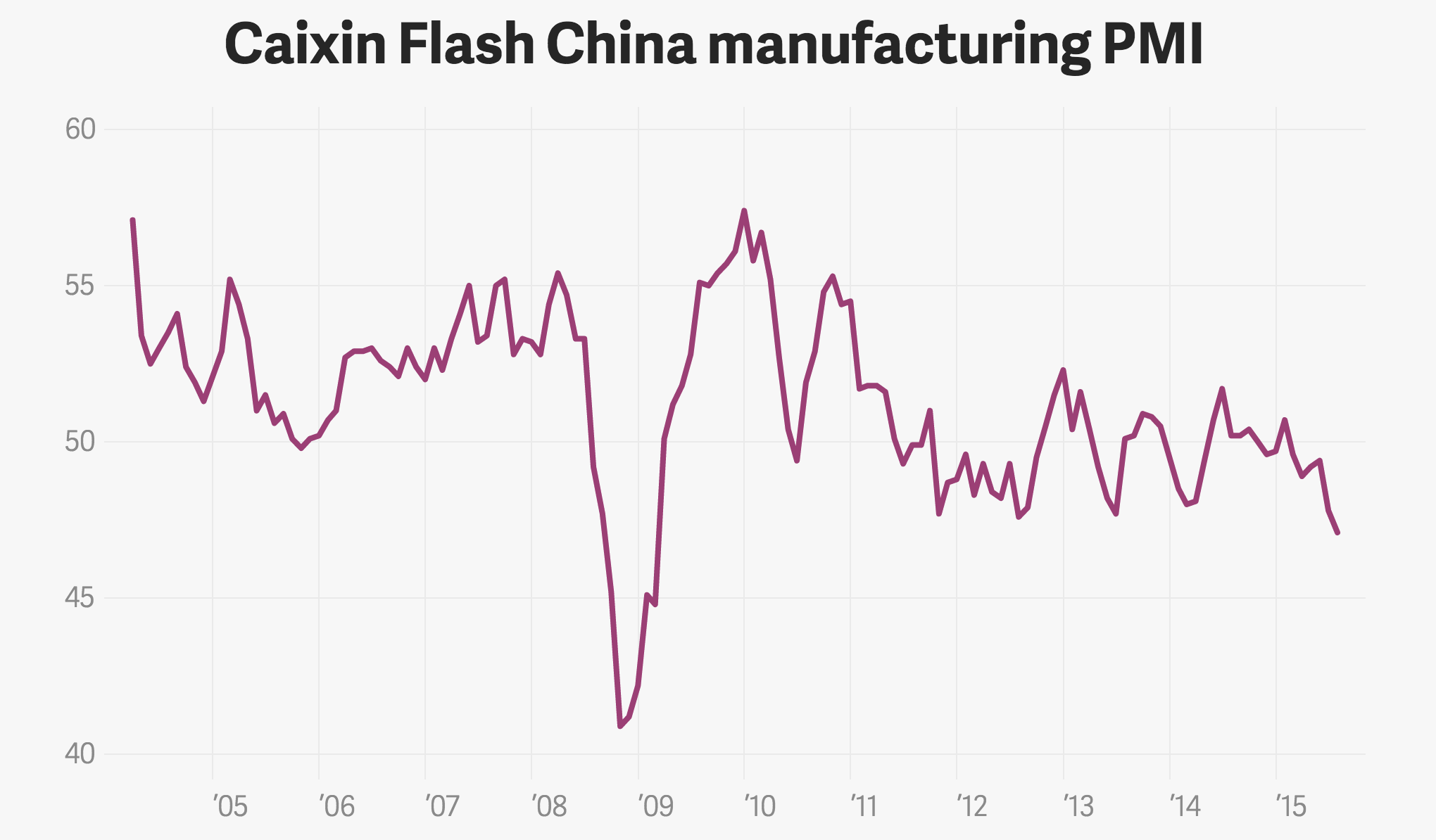

But the final straw appears to have been last week's release of a preliminary index for China's manufacturing activity. The August numbers took an unexpectedly sharp downward turn, to 47.1 from the 47.8 reading in July. (For context, any number above 50 is an expansion, and any below is a contraction, with the distance from 50 indicating the strength of the trend.)

Now, all these measures — demand, exports, imports, manufacturing, currency, etc — go up and down all the time. And none of these changes are that dramatic in isolation. It's all of them hitting in rapid sequence that's unnerving. And that observation only explains the psychology of the financial markets' response. It doesn't actually get at the question: Is the panic called for on the merits?

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

To which the answer is: probably not.

Here, for example, is the manufacturing index in context:

(Graph courtesy of Quartz, and data from Markit)

The latest downturn is noticeable, but not outside the range of recent activity. The collapse with the 2008 recession, and the second plunge in 2010, were both much more dramatic.

Furthermore, if you eyeball the graph, and account for the one-time shock of 2008, you can see a gradual downward trend that's been continuous over the last decade. Indeed, there's no reason to think the August numbers are outside the spread of normal statistical noise for that trend.

The background here is that the Chinese economy has been headed for a major and fundamental structural shift for some time. As the country's middle class grows and its wealth approaches that of the more advanced Western countries, China will no longer be able to rely on manufacturing and major industry as the base of its economy. Like the U.S., it will have to shift into being a primarily service economy.

In fact, it already is: The portion of China’s economy taken up by the service sector already outpaced the portion taken up by manufacturing a few years ago. The same Chinese financial outlet that released the manufacturing index also releases one for services, and it was at an 11-month high in July.

In other words, it's perfectly plausible to see all this as the relatively normal pains of a massive but necessary change. And there's really no concrete evidence it's anything other than that.

Now, there is a nightmare scenario. The short version is that China's corporations are saddled with enormous debt and high service payments. Meanwhile, a lot of private Chinese investment has been pouring into real estate. The country's gangbuster rise into the global middle class has provided it with an enormous amount of surplus wealth, and its weird communist-capitalist hybrid of an economy has jumped at the chance to pour those resources into various state-run projects that don't always work out. It has famously built whole "ghost cities" that have essentially been empty for years.

The sustainability of the government's finances and money-creation efforts depend on the health of the economy, which in turn depends on the government's skill in managing the economy. So if the slowdown gets bad enough and all that credit dries up, the whole thing could come crashing down.

If all that sounds eerily similar to America's situation in the run-up to the Great Recession, you're not wrong. But there's one big difference: In the U.S. case, the whole chain of debt was ultimately backstopped by screwy financial engineering and massive mortgage lending fraud. In China's case, precisely because the economy is still heavily state-run, it's backstopped by the Chinese government's ability to borrow and print money. The line between "private corporate debt" and "government debt" is just intrinsically hazy in this case.

China's official economic growth figures are widely considered unreliable, but there seems little doubt the reality is impressive by the standards of the advanced world. We just don't know how large the government's room to maneuver actually is, but there's little evidence-based reason to think it doesn't remain considerable.

The conviction that China is headed for inevitable collapse is largely ideological — driven by the conviction that American-style market capitalism is vastly superior to the whatever-it-is economy China has now. That's not a crazy proposition. But it's not self-evident, either. China's situation certainly doesn't appear to be stellar, but there's still a perfectly reasonable chance that it pulls off the long-term reform and transition ahead of it in a non-disastrous fashion. (The biggest hurdle to doing this is arguably China's governance structure, which ironically may not be centralized enough.)

At any rate, remember those "ghost cities?" They've actually been slowly filling up with very real people doing very real business.

Jeff Spross was the economics and business correspondent at TheWeek.com. He was previously a reporter at ThinkProgress.

-

5 blacked out cartoons about the Epstein file redactions

5 blacked out cartoons about the Epstein file redactionsCartoons Artists take on hidden identities, a censored presidential seal, and more

-

How Democrats are turning DOJ lemons into partisan lemonade

How Democrats are turning DOJ lemons into partisan lemonadeTODAY’S BIG QUESTION As the Trump administration continues to try — and fail — at indicting its political enemies, Democratic lawmakers have begun seizing the moment for themselves

-

ICE’s new targets post-Minnesota retreat

ICE’s new targets post-Minnesota retreatIn the Spotlight Several cities are reportedly on ICE’s list for immigration crackdowns