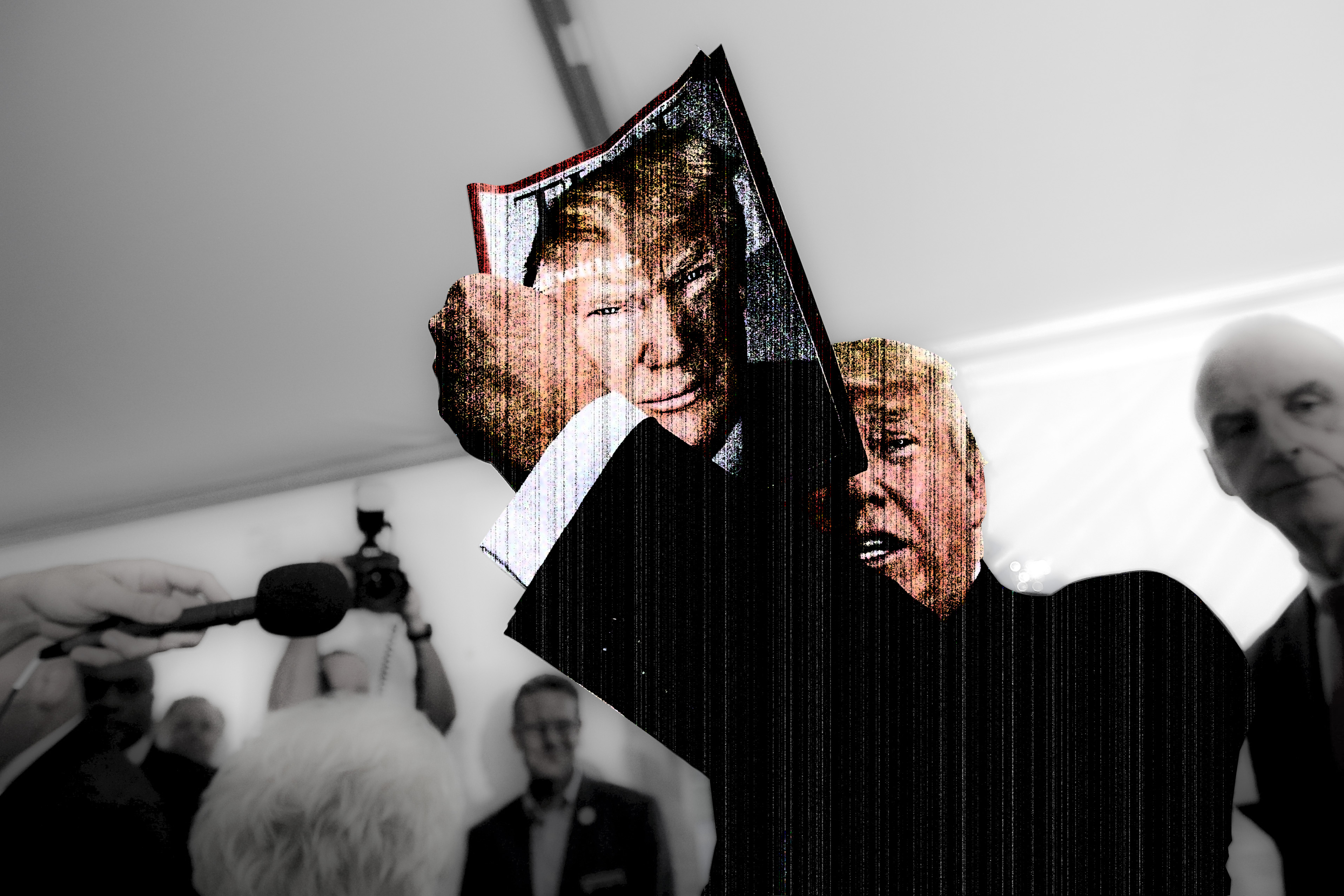

The Donald rises: Why Republicans want an anti-hero in 2016

Because America needs a gritty reboot

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

It was supposed to be the greatest Republican field of all time. The most highly-qualified, severely conservative, all-round competitive crop of candidates primary voters had ever seen. And they were supposed to be inspired.

Instead, they were Trumped.

The task has fallen to America's pundits to make sense of the mess. The prevailing wisdom has begun to settle on a very plausible explanation: Actually, the GOP field is lame and bogus. The governors have no foreign policy sense, we're told; the senators, no traction. Fiorina is a flash in the pan. Bush is a Bush. As National Review editor Rich Lowry put it in a sad denunciation of the back of the pack, "someone else will have to fill the screen" if Trump flames out — but "no one else has been big or vivid enough to do it."

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

True enough. But out here in Hollywood, it sure looks like the problem is more serious than a flat-footed field.

Let's be blunt. Today, a ton of Republicans don't want a hero.

They want an anti-hero — because America needs a gritty reboot.

Pundits mistake this for old-school populism. They watch Bernie Sanders pack them in while Hillary Clinton sucks wind and see shades of William Jennings Bryan. They watch Trump hoover up disgruntled Republicans and think, "Aha, Father Coughlin!"

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

But this isn't the populism of yore. Back then, regardless of their party ID, populists rallied around folk heroes — like the far-right Coughlin, the old-school liberal Bryan, or the actual-literal Socialist candidate, Eugene V. Debs.

Today we have no faith in political heroes. We don't want someone to deliver us, to lift us up. We want them to smash what's left of our dysfunctional world, beat down our intransigent foes, and leave us enough of a shot to sort out our lives amongst ourselves.

While the longing for an anti-hero is apparent on the left — hence the rise of Bernie Sanders — it's especially intense for Republicans. This marks the terminal stage of a long transformation.

Time and again, GOP primary voters have lashed out against the empty suits and mushy milquetoasts that the party establishment has thrown their way. Just ask Pat Buchanan, Herman Cain, Michele Bachmann, or Newt Gingrich. But that reflex, frustrated so many times, has given way to a deeper, more primal instinct.

So Scott Walker, who everyone wanted to be an anti-hero slathered in the blood of his enemies, has fizzled out because he wants to be heroic. Chris Christie, another would-be anti-hero, will never escape his Obama hug, the moment of sympathy that destroyed his credibility. Jeb Bush, neither hero nor anti-hero material, is just too cerebral. Even combative optimists like Carly Fiorina aren't scratching the itch.

But the critical case is Marco Rubio, a man about as traditionally heroic as Republican presidential candidates come. He might wind up winning the anti-Trump primary; he might unite every anti-Trump donor in the world. He may or may not know he's losing the contest between the hero vote and the anti-hero vote, but at least he knows that's the battle that matters. He's out on the trail saying so.

Explaining why he doesn't think Trump will be the nominee, he says the winner will "be someone that embraces the future, that understands the opportunities before us, that's optimistic but realistic about the challenges before us."

Although "people are angry," he says, Americans have "every reason to be optimistic about the future."

Many — oh so many — Republicans disagree. And so do many voters who aren't Republican.

They haven't given up on the future. They just know it's going to be darker than what they've been promised. They're not afraid; they know that with enough greatness and goodness, you can survive the darkness — eventually, even thrive.

It just takes a willingness to recognize how far we are from paradise.

Voters want a gritty reboot. Does any Republican know it — except Trump?

James Poulos is a contributing editor at National Affairs and the author of The Art of Being Free, out January 17 from St. Martin's Press. He has written on freedom and the politics of the future for publications ranging from The Federalist to Foreign Policy and from Good to Vice. He fronts the band Night Years in Los Angeles, where he lives with his son.

-

Political cartoons for February 3

Political cartoons for February 3Cartoons Tuesday’s political cartoons include empty seats, the worst of the worst of bunnies, and more

-

Trump’s Kennedy Center closure plan draws ire

Trump’s Kennedy Center closure plan draws ireSpeed Read Trump said he will close the center for two years for ‘renovations’

-

Trump's ‘weaponization czar’ demoted at DOJ

Trump's ‘weaponization czar’ demoted at DOJSpeed Read Ed Martin lost his title as assistant attorney general

-

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?Talking Point Peter Thiel and Larry Page preparing to change state residency

-

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one report

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one reportIN THE SPOTLIGHT By blocking an approved segment on a controversial prison holding US deportees in El Salvador, the editor-in-chief of CBS News has become the main story

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June

-

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardon

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardonTalking Point Convicted sex trafficker's testimony could shed new light on president's links to Jeffrey Epstein

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred