Is the economy maxed out of jobs?

Hawkish pundits say the labor market has basically reached full employment. But there's actually a lot of room for job growth.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

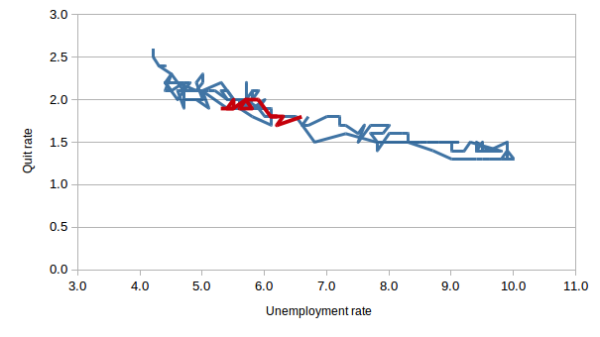

Since 2010, the world of economic punditry has periodically debated the question of whether the U.S. economy is even capable of creating more jobs. In March of last year, I got in one of those scrapes, over a chart made by economics blogger Evan Soltas of the quit rate (that is, the percentage of people leaving their jobs) versus the unemployment rate. Soltas found that the association was roughly in line with past trends, thus suggesting that labor markets were tightening up — i.e. approaching full employment — and that the Federal Reserve might have to raise interest rates to prevent inflation. I argued the evidence wasn't clear enough to justify such a move.

A year and a half later, it's a good time to check back in on this measurement to see how things have developed. In brief, I was right.

But first, let's present Soltas' original justification for the quit rate measurement:

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

This is new and, in my view, compelling evidence that labor markets are pretty tight. Why? Think about the decision to quit. It's a function of your confidence that you'll find a better job quickly — which embodies some unobserved but holistic measure of labor-market tightness. The fact that the unemployment rate appears to be a robust predictor of the quit rate both before and after the 2007-2009 recession suggests that the unemployment rate, our imperfect observation of labor-market tightness, is a close proxy for the tightness people think is important when they decide to quit or not to quit. [Economics and Thought]

I've created an updated version of his chart. It's a scatterplot of the monthly unemployment rate (on the x-axis) versus the quit rate, from January 2001 to the present. It's pretty messy due to lots of overlap, but there's a clear overall curve to be seen. As the unemployment rate increases, the quit rate decreases, because people are afraid they won't be able to get another job. As the unemployment rate decreases, the opposite holds.

However, it's not a very sharply defined curve. This can be seen in the measurement from March 2014 through the most recent data (July 2015), plotted in red:

Since March of last year, the unemployment rate has fallen by a full 1.5 points, from 6.6 percent to 5.1 percent. If this quit rate were going to follow the general trend, it should have increased substantially. Instead, it's moved a bare tenth of a point, from 1.8 percent to 1.9 percent, where it's been stuck for the past four straight months — thus the nearly straight leftward progress of the red line. Indeed, it's actually decreased slightly from earlier this year, when it briefly touched 2.0 percent.

To this we ought to add some more data. This whole measurement is supposed to be a proxy for the risk of inflationary pressure, but actual inflation has been below the Fed's target for the past three straight years — and is trending down, not up. The "financial stability" argument for raising rates has also been blown to smithereens, with market instability an accomplished fact worldwide. China is clearly suffering some serious economic troubles, and the strong dollar is hurting American manufacturers.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

In short, the Fed's evident desire to raise rates is, if anything, more inexplicable today than it was a year and a half ago.

But what should we take away from this? First is that no, labor markets weren't tight back in March 2014. We might conclude that maybe now they're getting tight, but given the chaos in other indicators, and the failure of this one indicator to work as previously theorized, we ought to be skeptical.

Fundamentally, the basic analysis Paul Krugman outlines here has never stopped being true. There will always be some reason or another to justify trying to slow the economy and prevent job creation (the class interest of the rich being the huge one that can't be stated outright). But we can't know for sure whether the economy is really going at full blast until inflation starts to increase — thus signaling the countrywide bidding war that means productive capacity is fully utilized.

Furthermore, while a bit of inflation is a minor annoyance that can be easily controlled, it might also be a positive good. Since 2008, the Fed has tried several rounds of unconventional economic stimulus because its main tool, the interest rate, has been stuck at zero. But more inflation lowers the real interest rate — making it easier to escape the zero lower bound trap, or avoid it in the first place.

Then there's simple right and wrong. Centrists often argue that it's not the central bank's job to act against inequality or long-term unemployment. But it's stone obvious that the people who will get the very last jobs created before full capacity is reached will be mostly from the bottom of society: poor people, minorities, ex-cons, and the long-term unemployed — in other words, the people who need jobs the most. Morally speaking, there is a vast difference between full employment and just shy thereof.

All this adds up to one conclusion: The Fed always ought to work very hard to achieve maximum job growth, especially when inflation is consistently below-target. Chances are there are a great many jobs left to be created, and we owe it to ourselves as a society to try.

Ryan Cooper is a national correspondent at TheWeek.com. His work has appeared in the Washington Monthly, The New Republic, and the Washington Post.

-

Will increasing tensions with Iran boil over into war?

Will increasing tensions with Iran boil over into war?Today’s Big Question President Donald Trump has recently been threatening the country

-

Corruption: The spy sheikh and the president

Corruption: The spy sheikh and the presidentFeature Trump is at the center of another scandal

-

Putin’s shadow war

Putin’s shadow warFeature The Kremlin is waging a campaign of sabotage and subversion against Ukraine’s allies in the West