Why Pope Francis is at least as qualified to pontificate on economics as U.S. conservatives

The high priests of Voodoo Economics are really going to lecture the world's highest-profile Christian? Really?

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

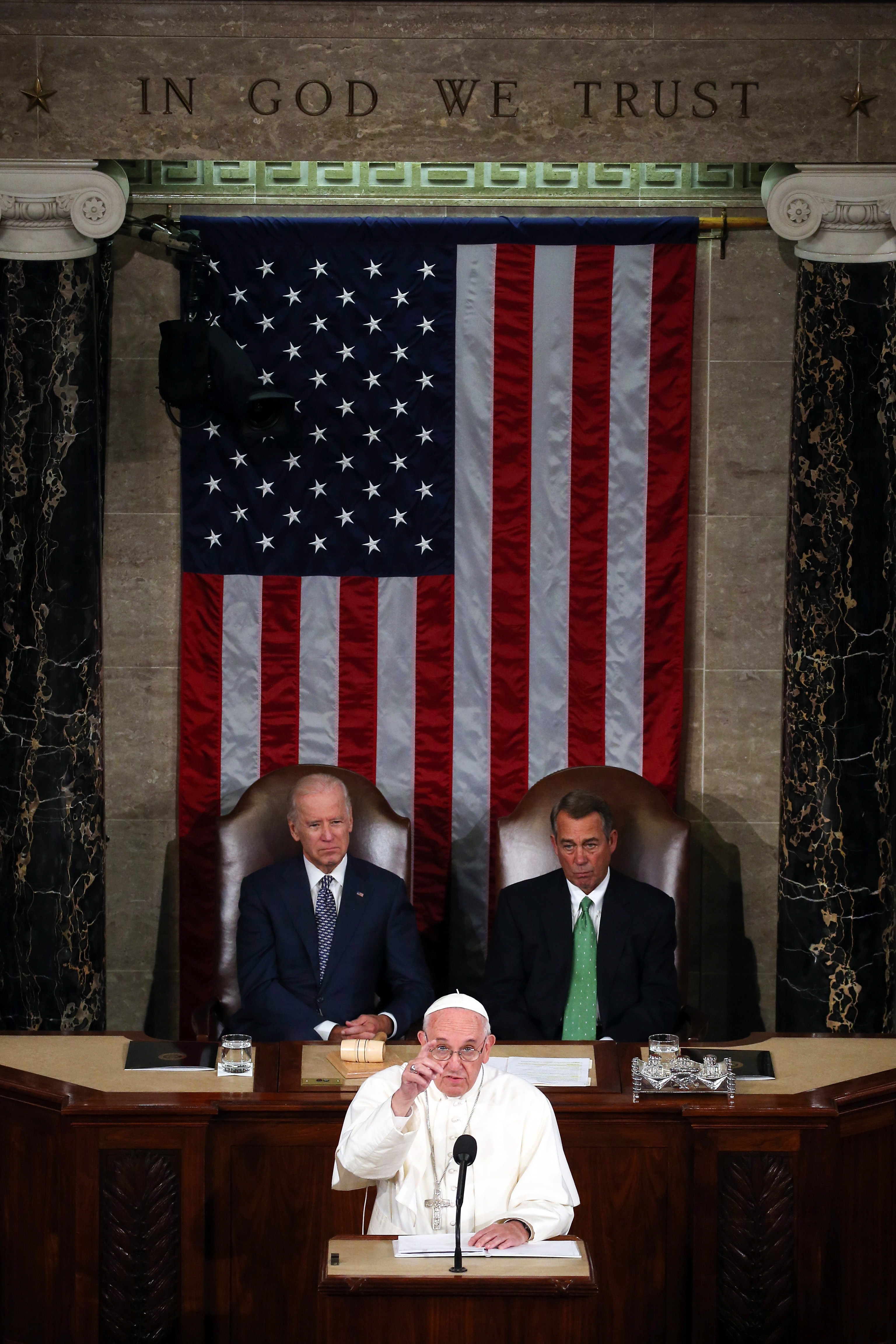

Pope Francis is in the U.S. for the first time, and American conservatives are welcoming him with a mixture of anxiety, hostility, and condescension. His sin, as Damon Linker explains, is addressing economics and the environment, two topics "close to the core of the Republican Party platform," and showing "he rejects the way the American conservative movement thinks about them."

The distillation of the tack U.S. conservatives are taking with Pope Francis is a tweet from David Limbaugh, the conservative author perhaps best known for being a brother of Rush Limbaugh: "I'm not a Catholic, but I agree with those Catholics who've said pope's statements on abortion/life are in his domain but economics are not."

Limbaugh cited a National Review article by Ramesh Ponnuru, a convert to Catholicism, who argued that Francis' views on economics "are his opinions, not the teachings of the church," by "a man whose understanding of economics has been shaped by an Argentinian political economy very different from our own." Not only is Argentina's experience with capitalism not valid, Ponnuru suggests, but Francis' "background is more pastoral," in contrast to his "immediate predecessors, Saint John Paul and Benedict," who were "scholar-intellectuals."

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Since Pope Francis is an intellectual lightweight from another country, conservatives should "cajole and correct and criticize the pope when appropriate," Ponnuru says, by which he means when Francis talks about economics and the environment, but not marriage or contraception or abortion. Ponnuru gets rather jesuitical in his discernment of what the Catholic Church is qualified to weigh in on, but he does at least concede that "politically conservative Catholics are used to having Church officials, including Benedict, disagree with them on economic matters."

That's kind of an understatement. Pope Francis employs a colorful use of language — in Bolivia in July, he famously called the "unfettered pursuit of money" and capital "the dung of the devil" (paraphrasing a fourth century saint) — but his ideas on economics are firmly rooted in at least 120 years of Catholic orthodoxy.

In his apostolic letter Evangelii Gaudium, Pope Francis appeared to take direct aim at Ronald Reagan, criticizing those who "continue to defend trickle-down theories" of economics that have "never been confirmed by the facts" and rely on "a crude and naïve trust in the goodness of those wielding economic power and in the sacralized workings of the prevailing economic system."

That really got the goat of conservatives, but popes have been criticizing unbridled capitalism since Pope Leo XIII's encyclical Rerum Novarum in 1891. And it's not just church leaders from Italy and Argentina, either. The U.S. Catholic bishops took on trickle-down economics at the height of the Reagan revolution, issuing an unflinching pastoral letter, "Economic Justice for All," in 1986, after years of research and consensus-building.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Conservatives didn't like that document then, and they don't like it now, but it was the official statement from the U.S. Catholic Church — and the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops affirmed the pastoral letter in 1996. "The bishops, although they have grown more conservative and shy of controversy during the last decade, did not seem at all hesitant about reiterating the claim" that food, shelter, and heath care are basic human rights, The New York Times reported at the time.

Religious and economic conservatives love to cite Pope John Paul II, but even the sometime Reagan ally and committed anti-communist wasn't on board with what George H.W. Bush famously called Reagan's "voodoo economics."

John Paul was anti-consumerism ("a web of false and superficial gratifications") and wrote about the need for organized labor, fair wages, environmental protections, and strong social welfare systems. And though his 1991 encyclical Centesimus Annus offered a (highly qualified) endorsement of capitalism, it also stated that "it is the task of the state to provide for the defense and preservation of common goods such as the natural and human environments, which cannot be safeguarded simply by market forces."

James Pethokoukis makes some fine points about the benefits of capitalism, respectfully pleading with Pope Francis to consider how "capitalism has created a globalized, technologically advanced world generating great wealth" and "opportunity for mass human flourishing almost unimaginable a century ago." But this pope doesn't appear to think that's the great progress U.S. conservatives, and probably nearly all Americans, consider it to be.

In Francis' encyclical Laudato Sí, he took aim at the West's "extreme and selective consumerism" and "throwaway culture," arguing that the developed world's voracious appetites are a bigger threat to the planet than population growth. Blaming overpopulation in poorer parts of the world, he writes, "is an attempt to legitimize the present model of distribution, where a minority believes that it has the right to consume in a way which can never be universalized, since the planet could not even contain the waste products of such consumption."

The current Bishop of Rome isn't an economist — though neither are most of his critics on the right, it should be noted — so does he have any right to publicly weigh in on economic matters? It's not a new question for the church.

"Bishops do not approach economic questions as experts in economics," said Milwaukee Archbishop Rembert Weakland when he unveiled the first draft of "Economic Justice for All" in 1984. "But, using the best evidence and data in that field, they reflect as teachers and pastors on the effects, both good and bad, that the economy has on people." One of the points of the pastoral letter, he added, was to "add our voice to the public debate about U.S. economic policies."

"Some ask, 'Why can't you just stick to what they call religious issues?'" said Spokane Bishop William Skylstad upon unveiling the 1996 follow-up document. "We need to be very clear. Our defense of the poor, our pursuit of economic justice, is fundamentally a work of faith."

You can argue that religion has no place in forming government policy — lots of people do — but that's emphatically not the case the U.S. conservatives are making.

If Pope Francis is working at least partly on faith, surely the same is true of boosters of supply-side economics. Conservatives can believe that the laissez-faire policies pursued by George W. Bush didn't directly lead to the 2008 economic crash, or that the tax changes pushed by Reagan aren't a primary cause of the growing chasm of disparity between the rich and the poor — they can believe that Reaganomics works. But plenty of real economists would find that faith naïve and misguided.

You can disagree with the pope on economics or the environment or any host of issues — again, plenty of people do, including Catholics of all political persuasions. But it's a little rich for the high priests of Voodoo Economics to be calling the Vicar of Christ an economic charlatan with nothing important to say.

Peter has worked as a news and culture writer and editor at The Week since the site's launch in 2008. He covers politics, world affairs, religion and cultural currents. His journalism career began as a copy editor at a financial newswire and has included editorial positions at The New York Times Magazine, Facts on File, and Oregon State University.

-

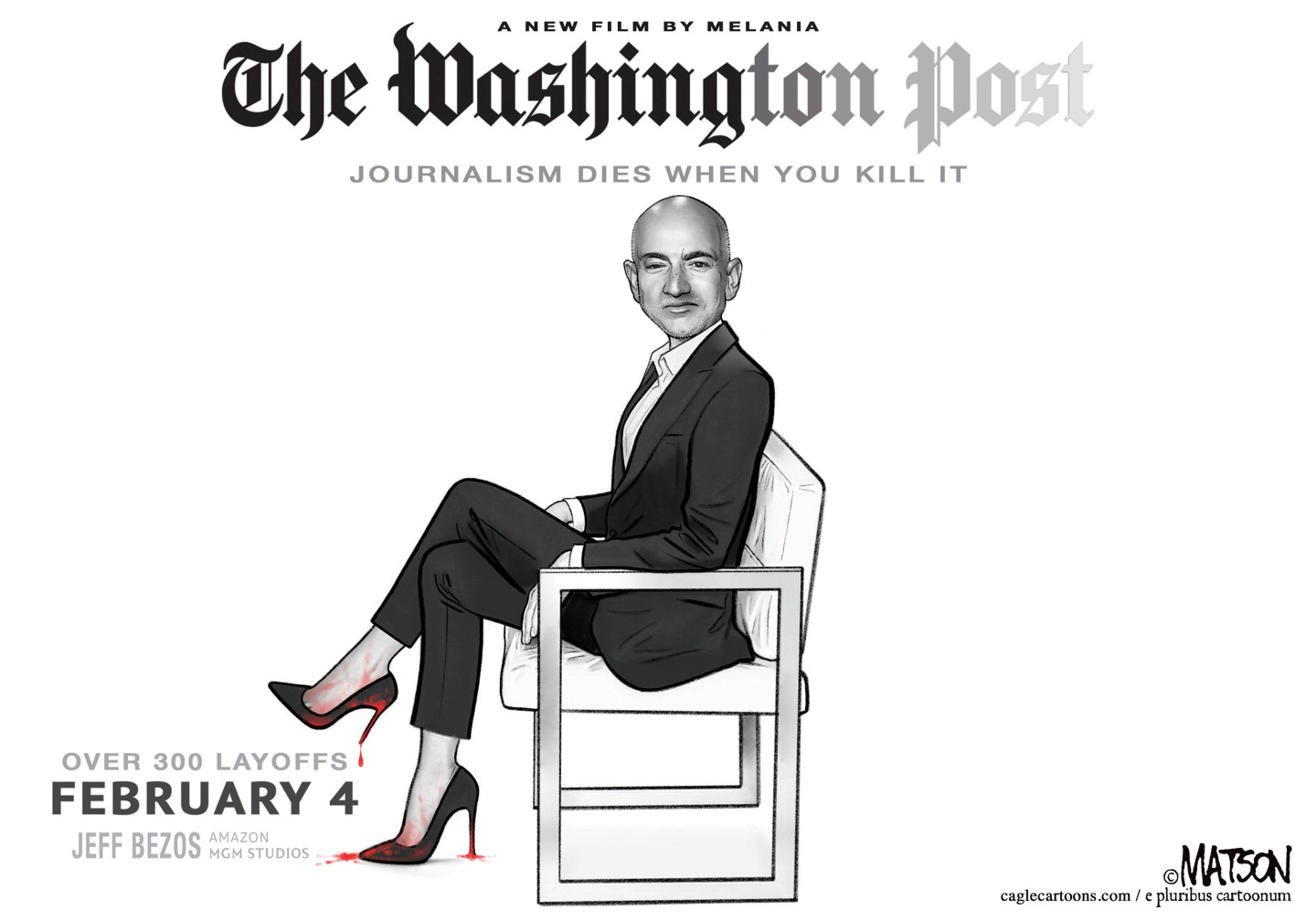

5 cinematic cartoons about Bezos betting big on 'Melania'

5 cinematic cartoons about Bezos betting big on 'Melania'Cartoons Artists take on a girlboss, a fetching newspaper, and more

-

The fall of the generals: China’s military purge

The fall of the generals: China’s military purgeIn the Spotlight Xi Jinping’s extraordinary removal of senior general proves that no-one is safe from anti-corruption drive that has investigated millions

-

Why the Gorton and Denton by-election is a ‘Frankenstein’s monster’

Why the Gorton and Denton by-election is a ‘Frankenstein’s monster’Talking Point Reform and the Greens have the Labour seat in their sights, but the constituency’s complex demographics make messaging tricky

-

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?Talking Point Peter Thiel and Larry Page preparing to change state residency

-

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one report

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one reportIN THE SPOTLIGHT By blocking an approved segment on a controversial prison holding US deportees in El Salvador, the editor-in-chief of CBS News has become the main story

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June

-

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardon

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardonTalking Point Convicted sex trafficker's testimony could shed new light on president's links to Jeffrey Epstein

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred