The weird economic netherworld of credit cards

Have you seen those new chip cards? They actually represent a rather crazy economic story.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

If you're a credit card user, you may have noticed the coming sea change: More and more U.S. credit card providers have been pushing out new cards with embedded electronic chips, and retailers have been rolling out new machines to accept them. It's all been to get ahead of a law change that hit in October, making retailers liable for fraud losses if they don't have the technology to accept chip cards.

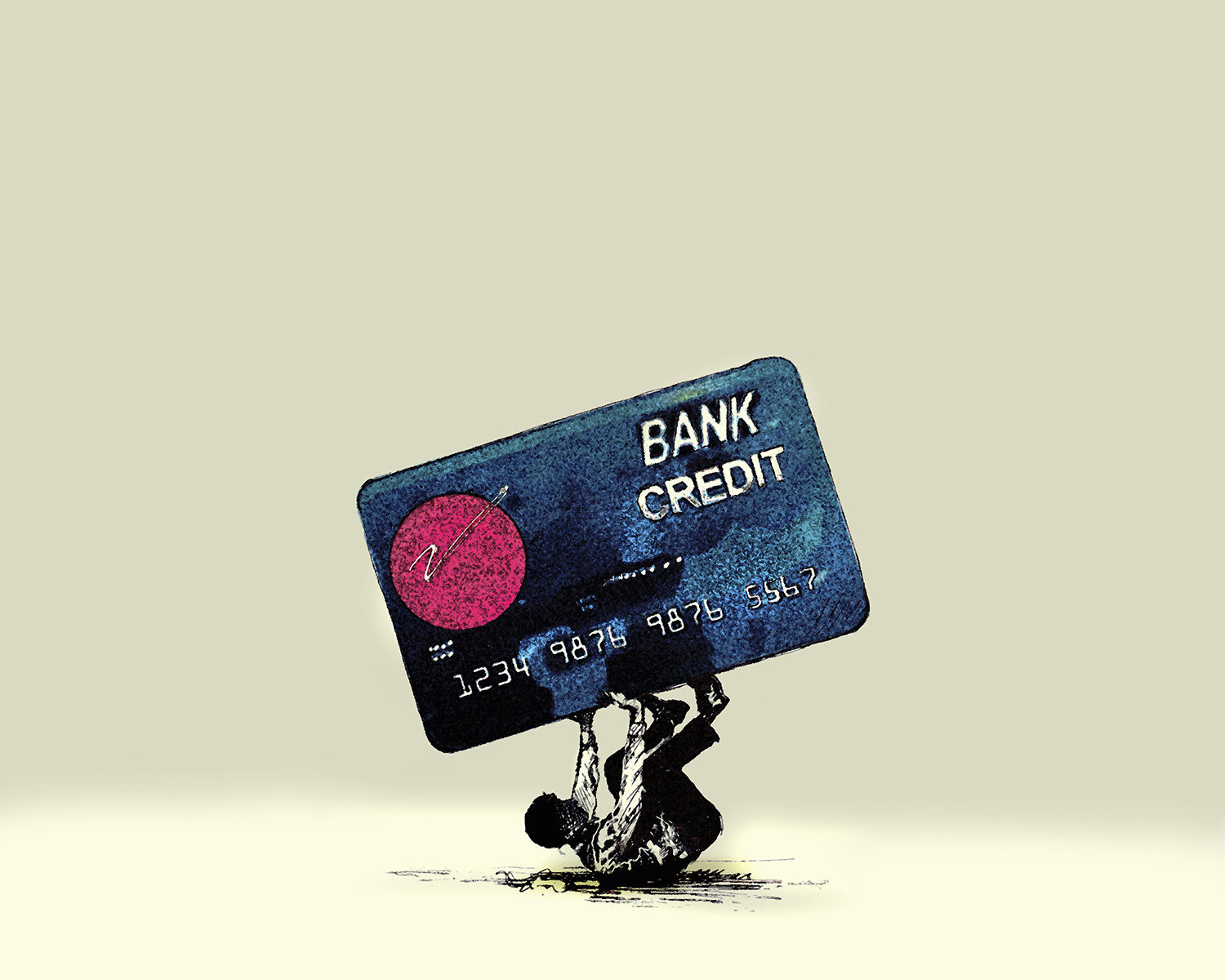

Needless to say, this has caused some tension between credit card suppliers and the businesses that rely on their services. And their spat is revealing a weird economic netherworld largely invisible to most credit card users, and one that turns how we think normal markets function on its head.

Some of the tension is pretty straightforward: Getting new cashier stations and other technologies that can read the chips is costly, sometimes in the tens of thousands of dollars. That's a one-time cost that's a big hit to the bottom lines of retailers, shops, restaurants, and all the other businesses that rely on credit cards.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Another point of contention — and this is where it starts getting weird — is that the credit card companies pushed the signature method in the first place. The PIN number system, an added layer of fraud protection in the new chip cards, has long been a feature of debit cards, which the credit card companies introduced in the 1980s. But because credit card companies charged businesses higher fees for signatures, Visa essentially forced everyone onto the signature system. It happened like this: Higher fees charged for signature-based transactions meant higher profits for the banks that issue cards, which in turn meant the banks had an incentive to go with signature system, which meant they issued more signature cards, which meant more businesses felt they had to go with the signature system or they'd lose customers. A ratchet effect set in that drove us towards the signature-based system.

This really gets to the heart of the dispute between businesses and retailers on one side and the credit card companies on the other: Namely, how close are the biggest credit card suppliers — Visa and Mastercard — to being monopolies? Various credit card companies, groups of merchants, and other major retail chains like Wal-Mart have been suing and counter-suing each other over this exact question for decades. And in the final technical and legal senses, that's a question that can only be settled by courts and judges as they apply antitrust law.

But as a practical matter, it's "kind of hard to look at it and say they're not monopolies," Bob Sullivan, an independent journalist who specializes in the credit card industry, and who has written a book on the subject, told The Week. "Whatever town you're in, the one store that's there that doesn't take Visa or MasterCard disappears, right? Unless you're in some unique market like restaurants in New York City. So they certainly would appear to be a monopoly power."

From the standpoint of economic theory, there a few things to understand here.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

The first is that credit and debit cards actually represent a four-way relationship: There are the banks that supply the credit cards, the credit card companies who actually just run the communication networks that make the cards work, the business who accept the cards to make transactions, and finally the everyday credit card users. Much like Facebook's customers are the advertisers, and not Facebook users, credit card companies' customers are the banks, and not the people who use credit cards. Which is why rising credit card fees charged to businesses are good for the banks.

This, in turn, creates a circumstance that's called the two-sided market effect. A third party (the credit card companies) is trying to make money by facilitating an exchange between two or more other parties (businesses and credit card users). And what generally happens in these instances is the third party gives one of the these two sides the transaction for free. Again, think of Facebook, giving away the service for free to most users.

Similarly, credit card users more or less get their cards for free. Sure, we pay interest rates and fees to the banks on occasion. But the businesses where we buy stuff with our cards get charged a fee for every single transaction. You give them a dollar, they only see 97 or 98 cents of it — the remainder goes to Visa or Mastercard and then on to the banks. And this can create a situation where the side of the transaction that's not getting it for free can be mercilessly squeezed: remember that once everyone has a Visa or Mastercard, businesses risk going under if they don't accept those credit card companies' terms.

Ostensibly, competition should help with this. But the costs of entry and technological deployment to new credit card companies are pretty high. So instead of the fees credit card companies charge business going down over time, which is what you'd expect from market competition, they've gone up. So businesses wind up paying credit card companies a rising fee simply for the privilege to participate in market activity at all. You can understand why they'd view this as fundamentally unjust.

One hope on the horizon that Sullivan pointed to is mobile pay apps like Samsung Pay, Apple Pay, or even something like Starbucks' app.

"Starbucks' app is far and away the largest mobile pay system. Something near 10 percent of Starbucks' transactions now occur with it," Sullivan explained. That saves Starbucks a ton of money in fees by cutting out the credit card middle man.

Of course, it's not clear yet how scalable mobile pay technology is, or whether small businesses can take advantage of it. In many ways, the problems of monopoly, two-sided markets, and transaction costs are built into the very fabric of what a credit or debit card is. That said, competition certainly couldn't hurt.

Jeff Spross was the economics and business correspondent at TheWeek.com. He was previously a reporter at ThinkProgress.

-

Magazine printables - February 13, 2026

Magazine printables - February 13, 2026Puzzle and Quizzes Magazine printables - February 13, 2026

-

Heated Rivalry, Bridgerton and why sex still sells on TV

Heated Rivalry, Bridgerton and why sex still sells on TVTalking Point Gen Z – often stereotyped as prudish and puritanical – are attracted to authenticity

-

Sean Bean brings ‘charisma’ and warmth to Get Birding

Sean Bean brings ‘charisma’ and warmth to Get BirdingThe Week Recommends Surprise new host of RSPB’s birdwatching podcast is a hit

-

The pros and cons of noncompete agreements

The pros and cons of noncompete agreementsThe Explainer The FTC wants to ban companies from binding their employees with noncompete agreements. Who would this benefit, and who would it hurt?

-

What experts are saying about the economy's surprise contraction

What experts are saying about the economy's surprise contractionThe Explainer The sharpest opinions on the debate from around the web

-

The death of cities was greatly exaggerated

The death of cities was greatly exaggeratedThe Explainer Why the pandemic predictions about urban flight were wrong

-

The housing crisis is here

The housing crisis is hereThe Explainer As the pandemic takes its toll, renters face eviction even as buyers are bidding higher

-

How to be an ally to marginalized coworkers

How to be an ally to marginalized coworkersThe Explainer Show up for your colleagues by showing that you see them and their struggles

-

What the stock market knows

What the stock market knowsThe Explainer Publicly traded companies are going to wallop small businesses

-

Can the government save small businesses?

Can the government save small businesses?The Explainer Many are fighting for a fair share of the coronavirus rescue package

-

How the oil crash could turn into a much bigger economic shock

How the oil crash could turn into a much bigger economic shockThe Explainer This could be a huge problem for the entire economy