Here's the political science behind the Trump and Sanders revolts

The tectonic plates of American politics are fundamentally shifting

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The tectonic plates of American politics are fundamentally shifting under the two parties.

Hillary Clinton — the Democrats' establishment candidate — will probably best populist Bernie Sanders for the nomination. But his campaign proved a vastly greater threat than anyone would've imagined. Meanwhile, the Republicans are in complete meltdown, as Donald Trump — a protean racist demagogue with zero concern for GOP orthodoxy — pretty much runs away with the party nomination.

What happened?

Article continues belowThe Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

The dominance of the two-party system means that the Democrats and Republicans alike are mixes of various ideological tribes and worldviews. These coalitions are not always stable. Every so often they break apart completely and reorganize, profoundly altering the nature of the parties that oversee them. (Think of how white Southerners abandoned the Democratic Party for the GOP following the civil rights movement.) This year is looking increasingly like another one of those realignments.

I'd argue the failure of both parties to accurately reflect American opinion on economic matters in particular is a root problem here.

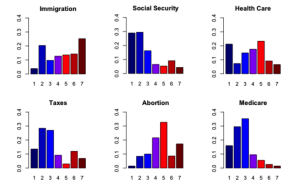

Political scientists David Broockman and Doug Ahler put out a paper in late 2015 that surveyed a bunch of Americans on a whole battery of issues — from Medicare to taxes to immigration — and gave them a range of seven positions to choose from on each. In the chart below, the seven choices for each issue are numbered 1 to 7, with 1 being the most left-wing and 7 the most right-wing. The bars show what portion of respondents picked each of the seven positions (so 0.1 on the y-axis means 10 percent, 0.2 means 20 percent, etc). The graphs are eye-popping:

(Graph from "Does Polarization Imply Poor Representation? A New Perspective on the 'Disconnect' Between Politicians and Voters" by Douglas J. Ahler David E. Broockman.)

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You can look through the paper to see other issues Broockman and Ahler surveyed (Figure 5), as well as the specific questions they asked (Appendix B.2, pages 39-45). But here's a general look at the most leftwing questions (option 1) respondents gravitated to: On health care, it was full socialism, i.e. have the government run the whole health care sector top to bottom. On Social Security, it was to increase current benefits and create new ones (cutting benefits was option 5 and privatization was option 6). For Medicare, it was basically health care socialism for seniors (option 5 was Paul Ryan's proposal, incidentally). And on taxes, it was to institute a 100 percent tax bracket on all income over $1 million. Meanwhile, immigration's popular right-most option was to halt all further legal immigration and deport all undocumented immigrants; for abortion, option 7 was to make it illegal under all circumstances.

We see these trends around economics borne out elsewhere. Efforts at direct federal job creation to invest and repair infrastructure (a big plank in Sanders' platform) — along with New-Deal-style government work programs — tend to win whopping majorities in polling. A survey by Vox based on Sanders' platform found 55 percent support for single-payer health care, 59 percent support for free college, and even higher enthusiasm for taxing the wealthy and corporations more. And when Larry Bartels and Jason Seawright examined the gulf in opinion between the wealthy and the general American public, they found similarly massive levels of support among the latter for the safety net, single-payer, a high minimum wage, government job creation, and the like.

So we have a situation where Democrats and Republicans encompass the full left-to-right sweep of opinion on issues like immigration, abortion, and gun control, but only represent the center-to-right spectrum on questions like entitlements, taxes, and health care reform. On matters of economics and material livelihood, huge portions of American voters have no one to represent them.

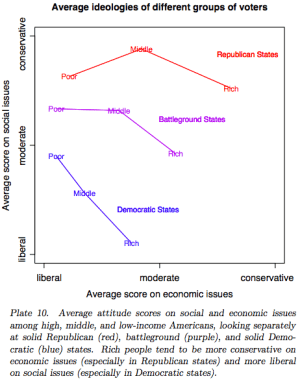

There are a few more pieces to the puzzle. Work by Andrew Gelman shows that people in the bottom third of the income distribution tend to be more socially conservative than the top third, but also more economically liberal.

(Graph courtesy of Andrew Gelman.)

Furthermore, economic issues are what drive poorer Americans' votes: Low-income voters regularly break overwhelmingly for the Democrats in elections. The trouble is that participation in voting and politics skews heavily towards the upper class, so the preferences of many poorer Americans simply aren't visible in our national policy debates.

The one other important thing Broockman and Ahler found was that voters don't gravitate to politicians who fit some overall moderate center; they gravitate to politicians who match them on the specific things they care most about. There is no such thing as a "moderate" in American politics. There are only people who scramble the issues we associate with the two major parties. Trump's combination of reactionary tribalism and (relative) economic liberalism is far more common than, say, Mike Bloomberg's mix of cosmopolitanism and business-friendly centrism.

The lesson for the Democrats is that, while Bernie Sanders may not be their nominee, it's ridiculous to argue he's too left-wing to be electable. There's a reason Sanders actually beats Trump and Cruz by bigger margins than Clinton in head-to-head polling matchups, and why he's been cleaning up among lower-income Americans. Beyond that, this isn't about any one candidate: there's an opening here for a left-populist economic movement sustained well beyond Sanders' campaign.

For the GOP, the terrifying lesson is that Donald Trump — who abandoned Republican zeal for cutting entitlements while going all in on a few reactionary issues, like immigration — speaks to the preferences of the general electorate more than the party platform.

Finally, if we are in a realignment moment, the Democrats need to move their economic agenda leftward in a hurry. The implicit gamble the party seems to be making with Clinton is that the Obama coalition can hold together without any serious tweaks to the platform. But so far it's only been challenged by elitist champions of standard GOP economic policies, and Democrats may be underestimating how much the instinctive economic liberalism of their various voter blocks kept the party glued together in response. The Obama coalition has never gone up against someone like Trump, and as my colleague Ryan Cooper pointed out, there's no guarantee it will hold together.

If the Clinton campaign doesn't adapt, they may well enter the general election by walking right into a populist buzzsaw named Donald Trump.

Jeff Spross was the economics and business correspondent at TheWeek.com. He was previously a reporter at ThinkProgress.