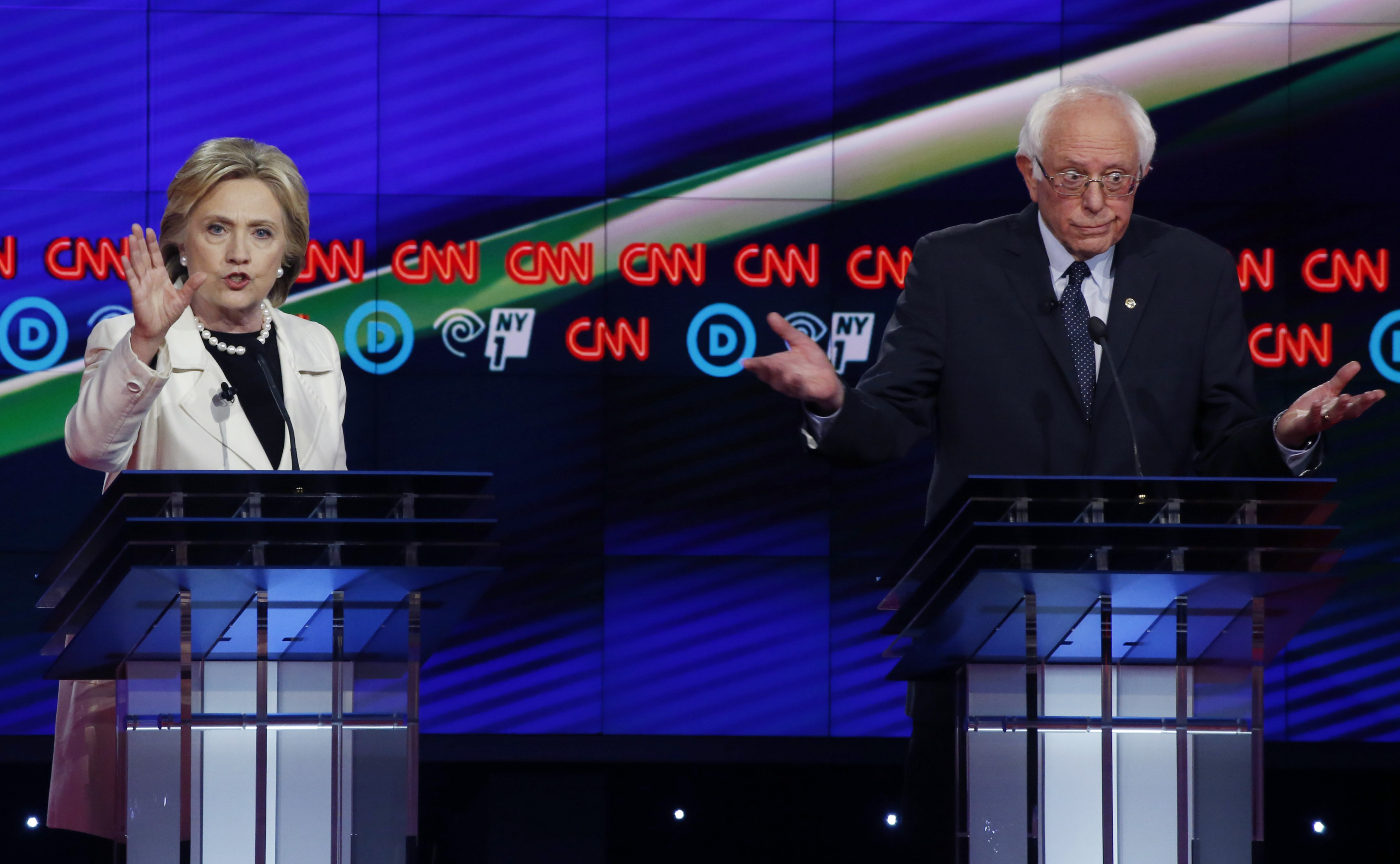

Bernie Sanders made his best case against Hillary Clinton in the Brooklyn debate. It wasn't good enough.

Bernie made a case against Clinton that sounds strong to those who buy what Sanders is selling. But he did not earn himself any new customers.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

They weren't playacting. In Brooklyn on Thursday night, Sen. Bernie Sanders went all in, with a high-risk, high-reward strategy, with the rewards accruing to him, and the risk consisting of the type of attack against Hillary Clinton that might stick to her in a general election.

To win the nomination, Sanders has to earn close to the same number of delegates that Clinton has already grossed, and to do that, he must score an upset victory in New York next Tuesday. To do that, he needed to do more than simply generate momentum. He had to intervene, take action decisively, and change the direction of the race. Among most Democrats, the die is cast; they think Clinton will be the nominee.

Sanders' string of recent victories has won him more money and positive press coverage, and has served to gin up resentment on many of your Facebook friends' pages. But Sanders' run of victories, particularly in smallish caucus states, haven't actually imparted any momentum to his campaign because Clinton consistently wins more actual votes and more actual delegates.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Thursday's debate was his final shot. He didn't really Kobe it, but he tried. He used everything he had, and more, even attempting to make the case the Obama administration (and Clinton) hadn't recognized the dignity of the Palestinians, or that Clinton was following Sanders by moving left on Social Security. (Not so.)

The edges of Sanders' case against Clinton are surprisingly soft, a jarring contrast to the high decibel level that he uses to make the charges. Clinton is beholden to her donors, he claims. She's the avatar of "the Wall Street economy," a proponent of a "rigged" system that Democrats must reject. And yet, when given the opportunity to point to specific policies that Clinton chose, or examples of quid pro quo, he chose instead to point to the speeches she gave to Goldman Sachs.

Those speeches are bad for Clinton, but they don't even approach the threshold for lending plausibility to his argument. Sanders' case against Clinton is plausible because of a pre-existing impression that many Democrats have (or fear is true) about the former secretary of state: that she'll say and do anything to win. Because he can't find actual facts to fit this argument, though, it rings hollow to everyone except people who already believe it. And it suggests, rather plainly, that Clinton is no more or less corrupt than anyone else inside the system — a system that Sanders himself is working to reform from the inside.

Clinton's refusal to release the Goldman Sachs speeches is either dumb or a calculated risk, or both. She has said she'll be happy to release the speeches when everyone else releases the texts of speeches they've given, falling back on a "one size should fit all" standard. No, no, and no. What Clinton told rich Wall Street executives is more germane by virtue of the facts of the Democratic debate. The standard is one of interest, not of fairness. By not releasing the speeches, she (and she must know this) gives every impression that she soft-sold her own view of the evilness of Big Money. Her own voting record suggests otherwise, which means that the speeches are either boring, or they contain a few cute turns of phrases that anyone who has ever given a corporate speech understands. No matter; the speeches need to speak for themselves.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

While there's probably nothing in the speeches that would incriminate Clinton, I think there probably is something in at least one speech that might embarrass her given the reality of the rest of the primary race. Perhaps she praised Goldman's commitment to corporate governance (at some point); perhaps she praised trade deals that Goldman favors (and she now opposes); perhaps she recognized the role that Goldman Sachs and others play in generating liquidity in our economy, and in ensuring that businesses can invest and take risks and hire more people. The speeches will come out before the election; they'll do so after Bernie Sanders has conceded the race to her. That's my guess.

And where are we now? We're back where we started. Sanders won the debate; he had to win the debate. He made a case against Clinton that sounds strong to those who buy what Sanders is selling. But he did not earn himself any new customers.

Marc Ambinder is TheWeek.com's editor-at-large. He is the author, with D.B. Grady, of The Command and Deep State: Inside the Government Secrecy Industry. Marc is also a contributing editor for The Atlantic and GQ. Formerly, he served as White House correspondent for National Journal, chief political consultant for CBS News, and politics editor at The Atlantic. Marc is a 2001 graduate of Harvard. He is married to Michael Park, a corporate strategy consultant, and lives in Los Angeles.