A brief history of TV shows' opening credit sequences

Today's opening sequences are elaborate works of art. But it hasn't always been this way.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The opening number of a television show has a big job to do. It has to convey, in a very short amount of time, the mood of the show you're about to watch, possibly introduce you to the characters, and set the tone for the next 30 to 60 minutes. But more than anything, it has to hook you.

Modern opening credit sequences are often works of art with stories of their own and an entire team dedicated to making them shine. Game of Thrones, for example, had 35 people and three months to work on the show's original opener. An artist first sketched the show's iconic map using pencil and paper before handing it over to the computer graphics department to fill in shadows, tint, color, and the technical aspects like the camera angles. It's no wonder The New York Times called this "the era of the elaborate opener."

But it hasn't always been this way.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

In the early days of television, opening credits served as little more than a platform for a show's sponsors to squeeze in some product placement. They were simple in their design: a few images, some names often read by an announcer, and a short instrumental accompaniment. The Honeymooners, for example, quickly introduced the cast before displaying a handsome car to let viewers know the show was brought to them by their local Buick dealer.

The 1960s brought huge changes to the American television landscape. TV was becoming a source of information, much like newspapers and radio had been previously. Americans were spending more time with their televisions and there were countless shows on the air. This meant people had more shows to choose from, and programs needed to find ways to stand out. As such, credits sequences started to become more important.

Gunsmoke, which aired from 1955 to 1975, originally featured the character Matt Dillon in a gunfight, but would eventually add a credit sequence about four minutes into the show:

Others like The Man from U.N.C.L.E., started to prominently showcase its cast at the start of each episode:

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

In the 1970s, the theme song was king and served as an explanatory anecdote for the show. The Jeffersons were "moving on up" in New York City and Mary Tyler Moore would, despite a few setbacks, "make it after all." This kind of obvious, hand-holding accompaniment continued through the 1980s, ensuring the opening credits reflected exactly what the show was about. The fast paced theme songs and clips from Miami Vice and Magnum P.I. told viewers that these were shows were about excess, adventure, and of course, flashy cars.

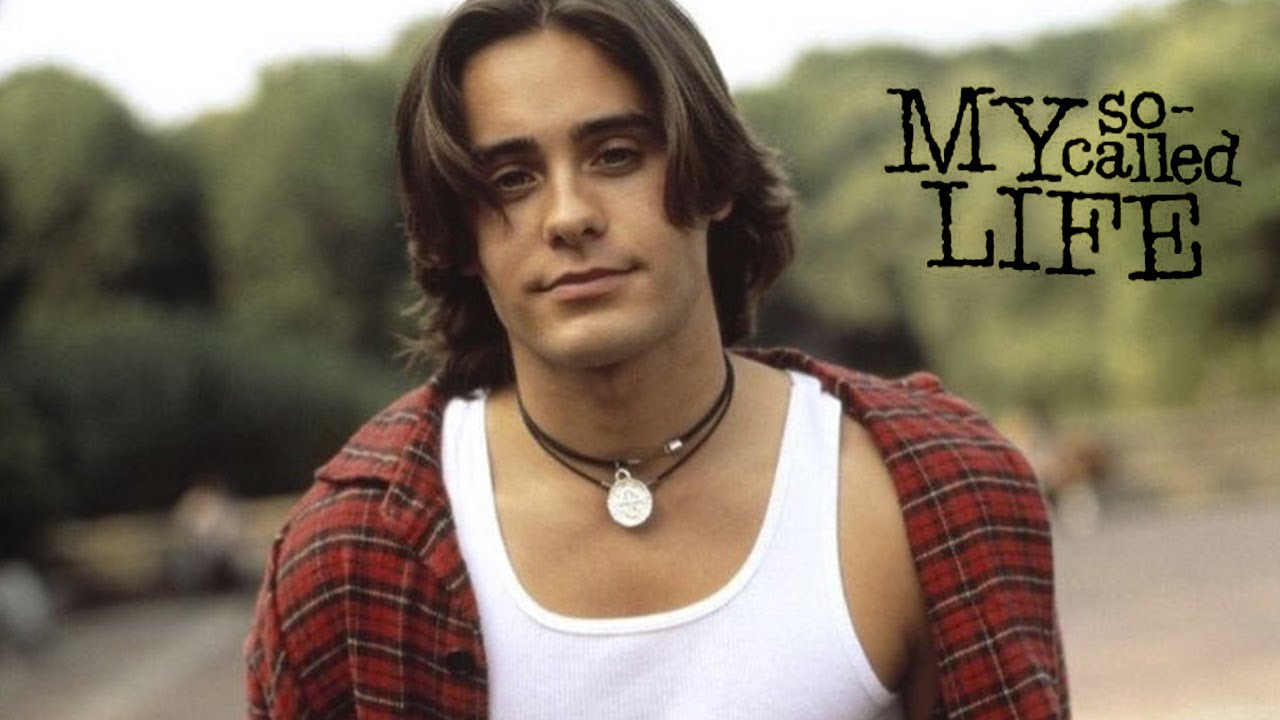

Opening credits sequences were at their peak in the early 1990s, but then the cracks started to form. By this time, they were actually starting to take up a bit too much space. Twin Peaks' opening clocked in at a whopping minute and 30 seconds, while Canada's North of 60 and teen drama My So-Called Life both took up a minute and 10 seconds.

Even half-hour sitcoms had long openings, like Family Matters, which featured one minute and 20 seconds of opening credits, leaving only about 18 to 19 minutes for the show itself.

These credits were cumbersome and no longer added much value for the viewer. By the late '90s, things really took a nosedive. Credits eschewed any kind of production value in favor of a catchy theme song by a popular artist. Dawson's Creek, for example, showed 45 seconds of blurry teenagers, accompanied by Paula Cole's "I don't want to wait."

Then, in 2003, LOST premiered, and with it, the title card, ushering in the swift decline of the lengthy opening credit sequence. The mystery drama opened with a 15-second intro featuring the word "LOST" spinning on a black background set to ominous instrumentals.

This minimalist approach demonstrated TV shows didn't need credits or a catchy theme songs to set a tone and get viewers; cast members could be introduced during the first scene, and people would still watch. Title cards also allowed shows to "dive right into the action," providing more screen time per episode. And of course, minimalist credits meant money saved.

Following LOST's innovative lead, shows like Ugly Betty and Heroes debuted without opening credits. Throughout the 2000s, others like Grey's Anatomy, One Tree Hill, and Desperate Housewives also abandoned their lengthy sequences.

By 2006, only about 10 percent of shows used a theme song or credit sequence to set up the story. "Clearly, brevity is key," The Associated Press reported in 2006. "No drawn-out intro or hokey theme. Networks don't have time for that — and neither, prevailing TV thinking goes, do the country's couch potatoes."

This wasn't so for premium networks like Starz, HBO, and Showtime, of course. The Sopranos famously indulged in a long tone-setting drive through New Jersey. Without needing to make time for commercials, prestige shows had more room to experiment with openings. And today, with the continued rise of streaming services like Netflix, long opening sequences are back, as you can see in shows like Jessica Jones, with its blurry, hand-painted noir-themed sequence, or Orange is the New Black's long slideshow featuring shots of real prison inmates' faces.

So, what's next for the opening credit sequence? As they say in television, "stay tuned."

Katie Ingram is a freelance journalist based in Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada. Her work has appeared in, among others, Halifax Magazine, Atlantic Books Today, SheKnows, J-source, Haligonia.ca and on CBC Radio.