Hillary Clinton's poverty plan is woefully inadequate

Seventy percent of the poor are either children, elderly, carers, disabled, or students. How will more jobs help them?

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

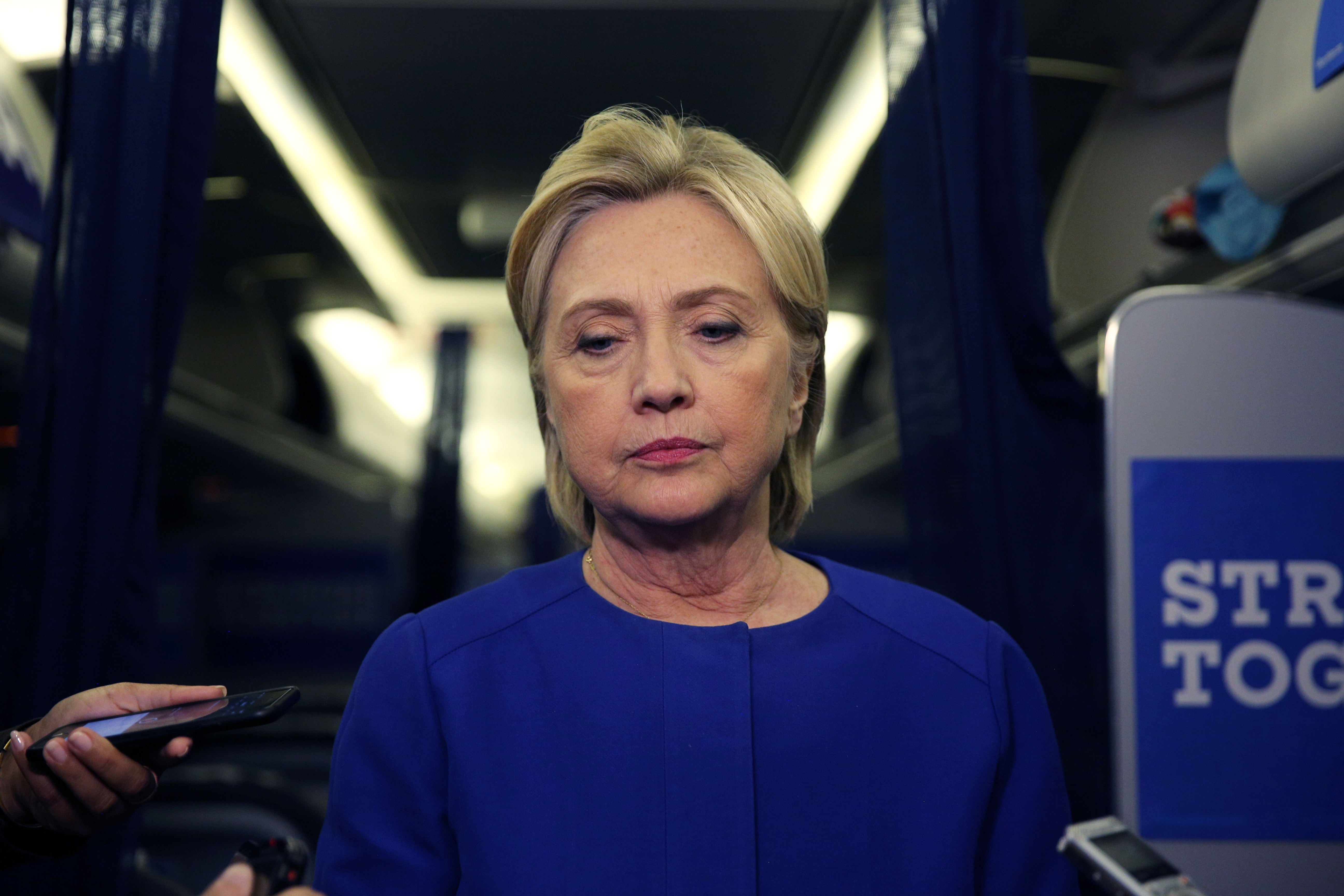

With Donald Trump's endless cavalcade of nonsense, and the endless attention to Hillary Clinton's minor email transgressions, policy issues have gotten virtually no attention during this campaign — and poverty policy least of all. That changed a bit this week when Clinton, to her credit, wrote an op-ed for The New York Times on Wednesday outlining her plan to reduce poverty. There's just one problem: It's lame.

The problem, at root, is the same one Paul Ryan has with his various anti-poverty ideas — a wildly disproportionate focus on work, and a corresponding lack of attention to the welfare policies that could seriously cut poverty.

Clinton's op-ed details a number of ideas, most of which are at least decent. She wants to direct 10 percent of federal investment to areas where 20 percent of the population has been living in poverty for at least 30 years, expand Low Income Housing Tax Credits (LIHTC) to create more affordable housing in expensive cities, "expand access" to child care, pass a paid leave plan, and institute universal pre-K.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

These ideas are mostly alright. Paid leave (Clinton's plan for this is inadequate, but it's a start), plus child care and universal pre-K, are vital necessities on their own that will nibble at poverty a bit, by providing some income to new parents and making it easier for parents of older children to work respectively. As far as tax credits go, the LIHTC is better than most, but it's still pitifully inadequate. In a country where over 21 million people pay more than 30 percent of their income in rent, the LIHTC supports only about 76,000 affordable housing units yearly — and only half of those are new. Also, it does nothing to actually increase incomes, only reduce the amount being spent on rent.

The 10-20-30 thing is a decent impulse hampered by the desire to package it in a cute slogan. While an all-out attack on concentrated poverty is certainly a great idea, it's baffling to restrict it in such a way. Why only 10 percent of federal investment? Why 20 percent poverty and not 18 percent? Why 30 years and not 25 years? Given that about a quarter of poor people are children, it's nutty to hinge help for them on whether or not their community has already been poor for an entire generation.

Clinton at least grudgingly acknowledges that extreme poverty has increased, but fails to mention that this is a direct and obvious consequence of her husband's welfare reform policy.

At any rate, the real problem is in this statement: "The best way to help families lift themselves out of poverty is to make it easier to find good-paying jobs."

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

This is nonsense. Again, more and better-paying jobs are a great policy objective, but it will have little purchase on the problem of poverty. Consider this chart breaking down the population of poor people in 2015 (according to the Supplemental Poverty Measure) by characteristic.

[[{"type":"media","view_mode":"media_large","fid":"167972","attributes":{"alt":"","class":"media-image","height":"394","style":"display: block; margin-left: auto; margin-right: auto;","typeof":"foaf:Image","width":"600"}}]]

Peruse the chart, and one thing jumps out: The huge majority of poor people are not employable. Some 71 percent of poor people are either children, disabled, elderly, students, or carers. A few of those people might conceivably work, but for the rest of that 71 percent, more and better jobs will help only insofar as they live with (or get cash from) someone who gets one of those jobs. Unemployed people would conceivably benefit a bit more, but then again capitalist labor markets are traditionally assumed to have to keep about 5 percent of the workforce unemployed at all times to forestall the dread inflation. The Economic Policy Institute did a best-case scenario looking at poverty reduction through wages, and found that even if you look at prime working-age people only, it would knock only about 4 points off the poverty rate.

Poverty is, at root, a shortage of income over a period of time. In a capitalist system, people who can't work will always be prone to being poor. Therefore, running the economy hot to produce good jobs and wages is a great idea, but it's a highly indirect way of attacking poverty at best. A better idea, seen in all the very low-poverty countries, is take the tax money thrown off by a thriving economy (and increased tax rates) and use it to fund generous welfare benefits for each category of poor-prone people: a child allowance, unemployment benefits, boosted Social Security for retired and disabled people, and so on.

The way liberals like Clinton favor means-testing and small, "targeted" initiatives makes it seem like the government is somehow really short of cash. But in reality, the United States is a very rich country with very low taxation compared to peer nations. There is no reason aside from political obstacles why we can't abolish poverty at a stroke. Fiddly little tax credits are just inadequate to the task.

Ryan Cooper is a national correspondent at TheWeek.com. His work has appeared in the Washington Monthly, The New Republic, and the Washington Post.

-

6 of the world’s most accessible destinations

6 of the world’s most accessible destinationsThe Week Recommends Experience all of Berlin, Singapore and Sydney

-

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule works

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule worksIn the Spotlight The law is at the heart of the Colbert-CBS conflict

-

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?Today’s Big Question Democrats want to rein in ICE’s immigration crackdown

-

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?Talking Point Peter Thiel and Larry Page preparing to change state residency

-

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one report

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one reportIN THE SPOTLIGHT By blocking an approved segment on a controversial prison holding US deportees in El Salvador, the editor-in-chief of CBS News has become the main story

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June

-

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardon

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardonTalking Point Convicted sex trafficker's testimony could shed new light on president's links to Jeffrey Epstein

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred