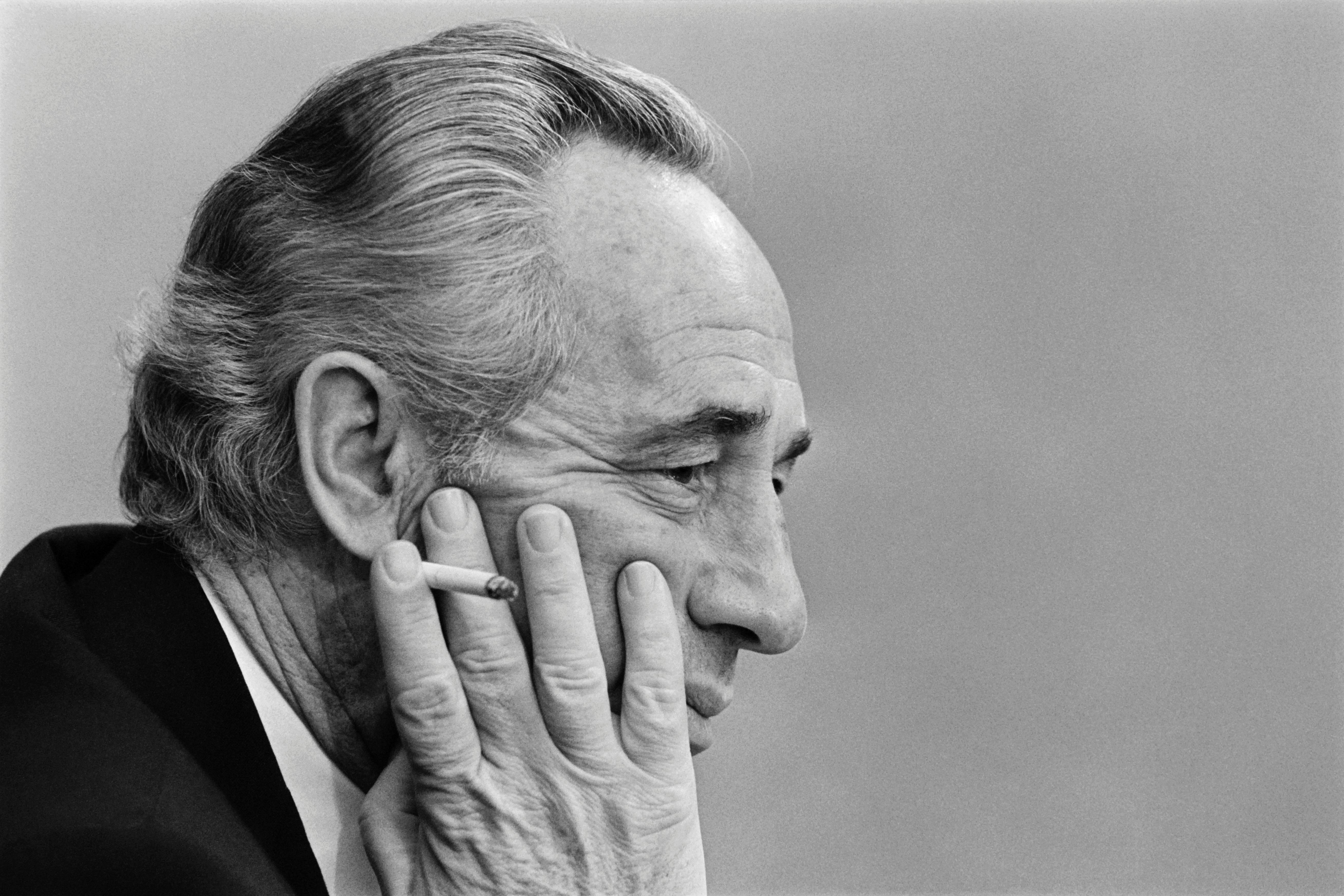

The last Zionist

Why Shimon Peres understood Israel's national interest better than any of his successors

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Shimon Peres, the last major figure from Israel's founding generation, died earlier this week at the age of 93. He may also have been the last major Israeli political figure to truly understand Israel's national interest.

That may seem to be a funny way to describe Peres. For some, both his admirers on the left and his fierce detractors on the right, he will be remembered as one of the visionary supporters of peace: an early advocate of peace with Jordan based on territorial compromise, a strong supporter of a regional peace to be achieved through the Madrid process in the early 1990s, and a prime mover on the Israeli side behind the Oslo Accords that established the Palestinian Authority. That hardly sounds like the portrait of a hard-headed advocate of the national interest.

Better-informed observers will know that this is far from the whole story. Peres was the man who forged an alliance with France to go to war with Egypt in 1956 and develop Israel's independent nuclear capability. He established the first Jewish settlements in land captured in the 1967 war, and fiercely advocated for their expansion in the decade that followed. Until his turn to the dovish left, he was known as "Mr. Security." Even as late as 1996, well after his turn toward the peace camp, he launched a brutal bombardment of Lebanon in response to Hezbollah attacks.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

The evolution of a politician from right- to left-wing, or vice versa, is not so remarkable, and complexity doesn't preclude seeing someone as a hero for a particular political side. But Peres was also, for most of his career, a deeply distrusted figure by all sides. His schemes to win the leadership of the Labor Party helped give the right-wing Likud its first opportunity to form a government. He repeatedly brought Israel's left-wing Labor party into coalition with Likud, sharing a rotating prime ministership with Yitzhak Shamir in the 1980s and joining Ariel Sharon's government (and then his new party) in the 2000s, but frequently conducting his own diplomacy outside the bounds of those governments' guidelines.

Both his ideological fellows and his opponents on the right frequently reviled him as an opportunist and a loose canon who would sell out any principle to retain power and achieve his personal aims. Indeed, he would even sacrifice his marriage to the need to remain in the national spotlight. How could someone so consumed by personal ambition possibly be described as a principled advocate of anything?

And yet, I still say it, precisely because of that apparent opportunism: Shimon Peres understood Israel's national interest better than any of his surviving successors, and devoted himself wholeheartedly to its pursuit.

Peres was indeed a strong advocate of peace. But he was an exceptionally unsentimental advocate. Peres understood that Zionism was an ideology with an endpoint: the establishment of a secure and sovereign Jewish state in the historic land of Israel. That security and that sovereignty could not be adequately assured without being accepted by the other countries of the region as a legitimate part of the region.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Israel's task, as he saw it, was a double one: to convince, by some combination of persuasion and force, the other states and people's of the region to accept Israel's permanence; and for Israel to adapt itself to the needs and interests of the region's other states and peoples so as to make that acceptance more palatable.

Precisely because the goal was acceptance, any subordinate interest — ideological, material, even moral — could potentially be sacrificed to that goal. Peres could be callous, even brutal, towards Israel's enemies. But he could be equally cold in sacrificing domestic interests, even those some of his ideological opponents considered sacred. He was an opportunist, and one with an exceptionally high opinion of his own importance. But that manifest opportunism and towering vanity were yoked to the service of an overarching strategic goal for his country.

People don't generally love leaders with that kind of cold but clear vision, and for most of Peres' career he was at best admired and respected, rarely loved (though his image softened considerably in his last years, serving in Israel's ceremonial but symbolically important presidency). Ironically, among the least likely to love them are those who loudly proclaim that they are hard-headed and nationalist in their orientation — because the nationalist impulse is at bottom an emotional one, a desire to feel championed, and not a hard-headed calculation of interest at all.

That nationalist impulse cannot be defeated merely by appeals to higher values. Israel's one-time center-left establishment learned this long ago — or should have, as every election they lost more and more ground to a right-wing bloc that disparaged wooly-minded "leftists" and postured as defenders of the nation, even as they made shibboleths of the quest for purely symbolic victories. Getting other countries to affirm that Israel is a "Jewish state," for example, would vindicate the national "narrative." But as Peres understood, that pursuit damaged the far more important and concrete interest of integrating successfully into the region.

Today, the rest of the world is catching up to Israel. This is a nationalist moment globally, and established parties around the world are finding themselves at a loss for how properly to respond to the challenge. Often, they fall back on the kinds of moralism that actually feed the vanity of the nationalists, implicitly crediting them with being free of sentiment when sentiment is precisely what drives them.

If that challenge is to be met, it will require politicians of the center who can demonstrate Peres' cold ruthlessness in pursuing national interests even when they conflict with nationalist sentiments — and who can do a better job than Peres did for most of his career of being loved for it.

Noah Millman is a screenwriter and filmmaker, a political columnist and a critic. From 2012 through 2017 he was a senior editor and featured blogger at The American Conservative. His work has also appeared in The New York Times Book Review, Politico, USA Today, The New Republic, The Weekly Standard, Foreign Policy, Modern Age, First Things, and the Jewish Review of Books, among other publications. Noah lives in Brooklyn with his wife and son.

-

The Olympic timekeepers keeping the Games on track

The Olympic timekeepers keeping the Games on trackUnder the Radar Swiss watchmaking giant Omega has been at the finish line of every Olympic Games for nearly 100 years

-

Will increasing tensions with Iran boil over into war?

Will increasing tensions with Iran boil over into war?Today’s Big Question President Donald Trump has recently been threatening the country

-

Corruption: The spy sheikh and the president

Corruption: The spy sheikh and the presidentFeature Trump is at the center of another scandal

-

Epstein files topple law CEO, roil UK government

Epstein files topple law CEO, roil UK governmentSpeed Read Peter Mandelson, Britain’s former ambassador to the US, is caught up in the scandal

-

Iran and US prepare to meet after skirmishes

Iran and US prepare to meet after skirmishesSpeed Read The incident comes amid heightened tensions in the Middle East

-

Israel retrieves final hostage’s body from Gaza

Israel retrieves final hostage’s body from GazaSpeed Read The 24-year-old police officer was killed during the initial Hamas attack

-

China’s Xi targets top general in growing purge

China’s Xi targets top general in growing purgeSpeed Read Zhang Youxia is being investigated over ‘grave violations’ of the law

-

Panama and Canada are negotiating over a crucial copper mine

Panama and Canada are negotiating over a crucial copper mineIn the Spotlight Panama is set to make a final decision on the mine this summer

-

Why Greenland’s natural resources are nearly impossible to mine

Why Greenland’s natural resources are nearly impossible to mineThe Explainer The country’s natural landscape makes the task extremely difficult

-

Iran cuts internet as protests escalate

Iran cuts internet as protests escalateSpeed Reada Government buildings across the country have been set on fire

-

US nabs ‘shadow’ tanker claimed by Russia

US nabs ‘shadow’ tanker claimed by RussiaSpeed Read The ship was one of two vessels seized by the US military