What might have been

We came so close to having our first female president. But we are still so far away.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

America is 240 years old. She has had 44 presidents. They have all been men. Indeed, with the exception of No. 44, they have all been white men.

This year, America had a chance to make history — to put an end to the boys club by electing a woman to our nation's highest, most powerful office. Instead, we elected Donald Trump.

This is a crushing blow to women. Not because we all oppose Trump, or because we are all Hillary Clinton supporters. Far from it. In fact, this isn't really about Hillary Clinton at all. It's not about her experience, achievements, or policies. It's not about her character flaws, leaky emails, or FBI trouble.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Set Hillary Clinton aside. This is about something bigger than whether or not you were with her. This is about the painfully slow lurch of progress. It's about what could have been for women — and the country as a whole.

This country sprung from the roots of patriarchy, and women have been snarled in its vines ever since. But that doesn't mean they accepted it quietly.

In 1776, Abigail Adams wrote a letter to her husband, Congressman John Adams, who had been appointed to the committee that would draw up a new set of laws severing the colonies from the British. She asked her husband to "remember the ladies."

"Be more generous and favorable to them than your ancestors," she wrote. "Do not put such unlimited power into the hands of the husbands. Remember all men would be tyrants if they could."

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

The Adamses enjoyed a unique relationship for the time period, one based on mutual respect, ambition, and equality. And yet, even John Adams, the closest thing the colonists had to a feminist, disregarded Abigail's proposition as the ramblings of a silly woman, writing that he could not help but laugh at her "saucy" letter.

The Declaration of Independence declared that "all men are created equal." And my, did that "men" set a precedent. The rights and liberties so eloquently set forth by the Founding Fathers did not extend to all people, particularly not to African Americans or women. As the Declaration of Independence gave birth to a new nation, it snuffed out, with remarkable purpose, the political identity of much of the population.

Beginning in 1777, women were systematically disenfranchised in each of the 13 colonies. While a single woman still enjoyed some autonomy — including the freedom to live where she wanted, to buy and sell property, and to earn money — a married woman had no identity under the eyes of the law. Alexis de Tocqueville noticed the vastly different status of men and women during his trip to America in 1831: "In America a woman loses her independence in the bonds of matrimony," he wrote.

In 1848, Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Lucretia Mott set up the Seneca Falls Convention, the first meeting of the Women's Rights Movement. With the help of the 300 attendees, Stanton and Mott drafted the most significant document in the advancement of women, the Declaration of Sentiments. It argued that women had the right to equality in all aspects of their lives, including, and most significantly, the right to vote.

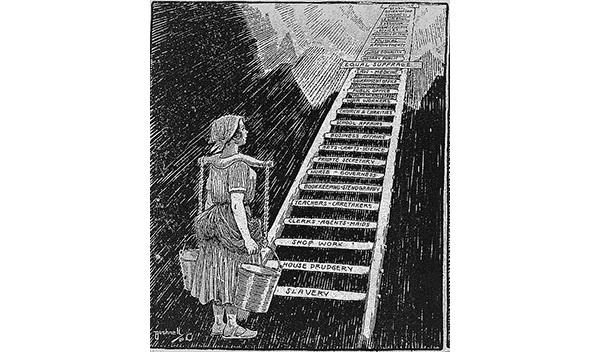

It would take another 72 years before women actually earned that right. But Stanton, Mott, and the Women's Rights Movement armed women for the long battle ahead, calling on them to pull themselves out from their inferior positions, to fight for what was theirs.

The trouble was, no matter the progress women made, the America they were muscling themselves into wasn't theirs to control. As the French philosopher Simone de Beauvoir wrote in her landmark study of women, The Second Sex: "This world that has always belonged to men is still in their hands."

In 1916, Jeannette Rankin became the first woman elected to Congress. Since then, women have slowly gained representation in American politics. But even after a century of trying, it still hasn't reached critical mass. The widely agreed upon level for women to have a real impact among a group of men — whether in a classroom, boardroom, or in Congress — is 30 percent. America's 114th Congress hits only 20 percent.

Still, female congressional members are more likely than men to sponsor women's issues bills and speak on the House floor about women. Both Republican and Democratic female legislators introduce more progressive bills than men, focused on civil rights and liberties, as well as health and labor. They are also more likely to consider how legislation will affect women across the country, not just those within their jurisdiction.

Female representation also boosts society as a whole. During the 2013 government shutdown, it was a bipartisan group of women senators whose negotiations formed the centerpiece of the deal that got the government back to work. Beyond America's shores, countries that elected a woman to the top leadership position had greater GDP growth than countries with a male leader. Women entrepreneurs are more likely than men to lead successful firms. Companies with more women in the highest corporate offices correlate with higher profits. And companies with more women on their boards outperformed their rivals.

But progress in the corporate world is even slower than in government. The number of female CEOs in America's 500 biggest companies dropped in 2016, to just 4 percent.

The fight for ideal or even baseline equality is far from over. Women continue to be held back by the country's inherent patriarchy. But as we inch closer to equality, the good news is that the empowerment of women has a multiplier effect. An enlightening study looking at the West Bengal region of India found that girls who grew up in villages with long-serving female leaders set higher goals for themselves and increased their ambitions.

There is no office higher than president of the United States. It is nothing if not symbolic when someone who is not a white man reaches that final rung on the ladder. After President Obama achieved his historic moment in 2008, Rev. Jesse Jackson said that Obama's election "shows that there's nothing else we can't be. There's no university we can't be seriously considered to lead. There's no bank we can't be considered in if we have the right credentials."

The election of a woman to the presidency would have been a symbolic liberation for all women — a machete to those patriarchal roots. Alas, America's voters chose something different.

And so it's left to women to continue to lift ourselves out from our inferior position, to muscle our way into a country that remains in the grip of men.

"To every little girl out there, never doubt that you are valuable and powerful and deserving of every chance and opportunity in the world to pursue and achieve your own dreams," Clinton said in her concession speech Wednesday. "This loss hurts but please never stop believing that fighting for what's right is worth it."

I have a young daughter. I wanted so badly for her to wake up to a new reality on Wednesday — one that represents real progress, the kind that occurs when a woman president is just a fact of life. Such a thing would so widen the aperture on the lens to her future.

But for now, it remains outside the bounds of reality. We can only imagine it.

Lauren Hansen produces The Week’s podcasts and videos and edits the photo blog, Captured. She also manages the production of the magazine's iPad app. A graduate of Kenyon College and Northwestern University, she previously worked at the BBC and Frontline. She knows a thing or two about pretty pictures and cute puppies, both of which she tweets about @mylaurenhansen.

-

The Gallivant: style and charm steps from Camber Sands

The Gallivant: style and charm steps from Camber SandsThe Week Recommends Nestled behind the dunes, this luxury hotel is a great place to hunker down and get cosy

-

The President’s Cake: ‘sweet tragedy’ about a little girl on a baking mission in Iraq

The President’s Cake: ‘sweet tragedy’ about a little girl on a baking mission in IraqThe Week Recommends Charming debut from Hasan Hadi is filled with ‘vivid characters’

-

Kia EV4: a ‘terrifically comfy’ electric car

Kia EV4: a ‘terrifically comfy’ electric carThe Week Recommends The family-friendly vehicle has ‘plush seats’ and generous space

-

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?Talking Point Peter Thiel and Larry Page preparing to change state residency

-

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one report

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one reportIN THE SPOTLIGHT By blocking an approved segment on a controversial prison holding US deportees in El Salvador, the editor-in-chief of CBS News has become the main story

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June

-

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardon

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardonTalking Point Convicted sex trafficker's testimony could shed new light on president's links to Jeffrey Epstein

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred