How to make a carbon tax insanely popular

And fair, too

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

In the pantheon of policies to address climate change, few are more ambitious than a carbon tax.

The basic idea is to slap a fee an every ton of carbon pumped out by the burning of fossil fuels, usually charged at the point where the coal, oil, or natural gas is extracted. The cost of that fee then filters through the economy, arriving finally in the bills of consumers and raising the price of any form of energy that emits carbon dioxide.

What's great about a carbon tax is that it cuts directly to the heart of the problem: The cost of future damage from climate change isn't reflected in the price of fossil fuels. The idea behind the tax is that if the damage was reflected in the price, the markets would naturally adapt, evolving to rely more and more on green energy.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

This gives carbon taxes a certain cross partisan appeal: Liberals and leftists concerned with climate change can unite with center-right types who prefer market-friendly solutions. In fact, a group of prominent Republicans and conservatives — including former George H.W. Bush Secretary of State James Baker, and economist Gregory Mankiw — is making a renewed push for a carbon tax right now.

But the idea comes with one big problem: Implemented in a vacuum, a carbon tax leaves the poor and the middle-class worse off. They have far less room in their budgets to handle a sudden increase in the cost of their gas, heat, and electricity bills. So raising the price of fossil fuels the same amount for everyone doesn't share the burden equitably. So what you do to offset the burden of the tax matters enormously.

A new paper by Anders Fremstad and Mark Paul — just released by the Political Economy Research Institute — clarifies just how serious a problem this is and offers a way to fix it.

Now, this problem is hardly new. Carbon tax policy enthusiasts have proposed cutting income or corporate taxes by the same amount the carbon tax takes from the economy. Or even dividing up that pot of money into equal checks sent out to every American. We'll call that last one the per capita dividend.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Fremstad and Paul's contribution comes in a few areas.

First off, they compare three ways to offset a carbon tax of $49 per ton of carbon dioxide: A broad reduction in taxes on labor income, a reduction in the payroll tax specifically, and the per capita dividend.

Second, they get very detailed about the impact of the carbon tax from household to household. They break different industries and commodities down by how much carbon they emit, and then use consumer data to pick apart how much different households rely on those industries and commodities. Why does this matter? Well, even if two different households contain the same number of people and make the same amount of money, one might be in the city and one might be out on the farm. They'd face two very different cost of living situations, and consume energy in two very different ways. So the carbon tax (and whatever offsetting program you pick) would affect them very differently. If you just lumped them together into the same statistical bucket, you'd miss those details.

The results Fremstad and Paul get from all this are pretty dramatic.

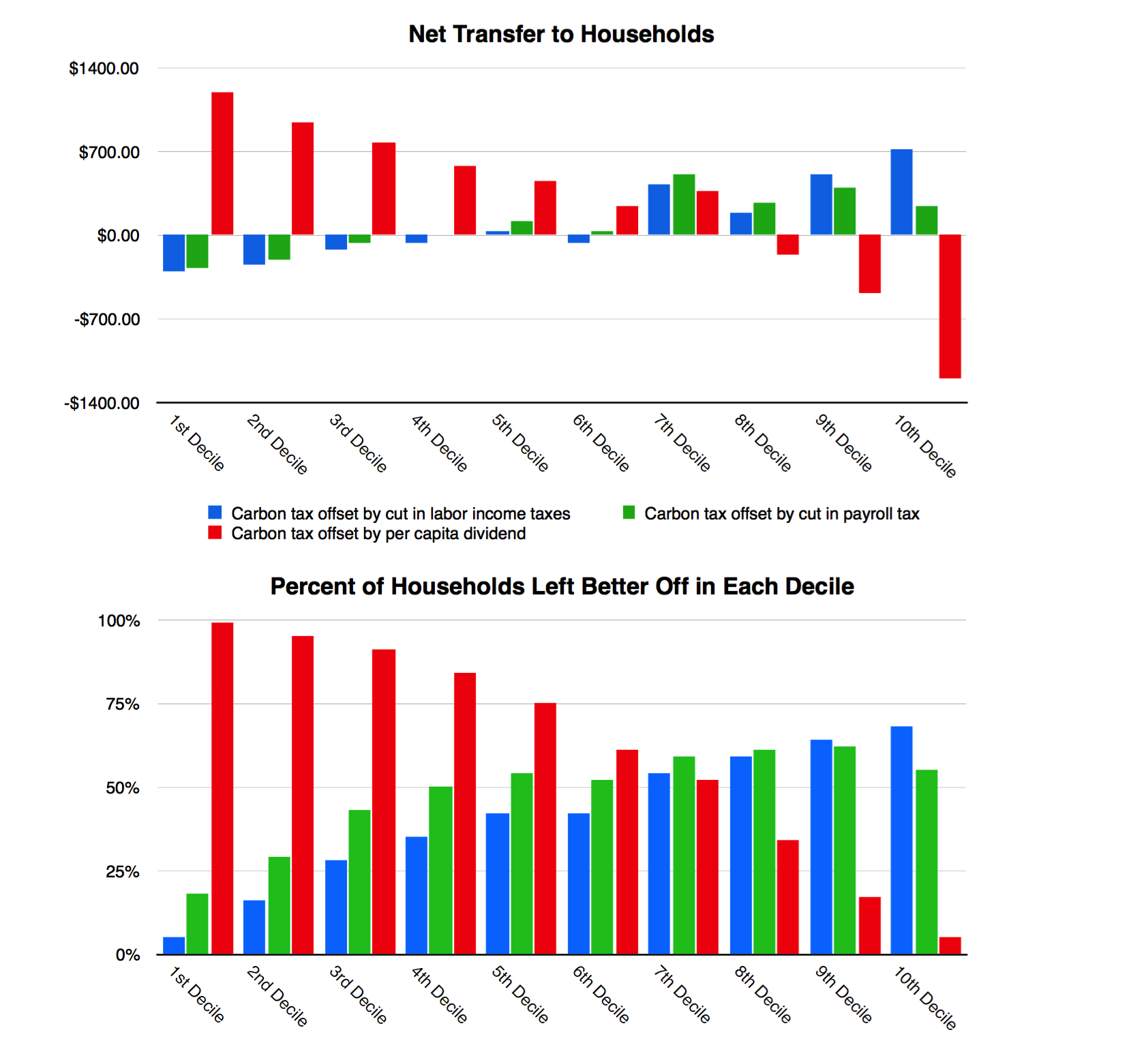

In the graph below, American households are divided into 10 groups — called "deciles" — each representing a tenth of the population. The first decile is the poorest 10 percent of households, the second decile is the second poorest 10 percent, and so on.

The top graph is how much the average household in each decile would lose or gain under the three scenarios. (General tax cut in blue, payroll tax cut in green, per capita dividend in red.) But we're talking averages, so the effects within each decile will vary. The second graph goes inside each decile, and shows how many households are left better off by any amount under that policy scenario.

With a carbon tax that's offset by either a cut in labor taxes or a cut to the payroll tax, the bottom half of Americans are still left worse off than they were before. The bottom 10 percent as an aggregate population lose almost $300 per household on average. And when you dive deeper, only 5 to 18 percent of Americans within the bottom 10 percent are left better off. You have to get halfway up the economic ladder before each decile is made better off on average.

This is a particularly dramatic result for the payroll tax offset. It's a pretty regressive tax so cutting it should have a progressive effect. But it's just overcome by the sheer weight of the carbon tax itself.

It's only when you offset the carbon tax with the per capita dividend that you get the result you want: The bottom two-thirds of households are made better off, the vast majority of households within each of those deciles is made better off, and the poorest households benefit by the greatest amounts.

"A lot of time people posit the environment against the poor, saying curtailing emissions will particularly hurt the poor," Paul told The Week in an interview. "And they're right. But through proper policy design we can really address that."

One thing worth mentioning is that the economic model Fremstad and Paul used to calculate this — called an "input-output" model — has strengths and weaknesses. It provides a very granular look at distributive impacts, but it also only gives a snapshot in time. It doesn't say how the economy will evolve over years.

There's a good argument that this is the right way to look at it. A lot of other modeling approaches will tell you how the overall economy would evolve under a carbon tax, but they can't give you that granular detail. So policymakers get excited when a carbon tax offset by other tax cuts creates more aggregate growth. But they don't grapple with the distribution of impacts within the aggregate.

Most voters, meanwhile, are probably going to be most concerned with how a carbon tax immediately affect them rather than with whether the overall economy will grow years down the line.

So what to take from this?

Coalitions created across the traditional liberal-conservative or Democrat-Republican divides will be in trouble. Right-wing supporters will push towards offsetting the carbon tax with other tax reductions, or elimination of regulations. Baker and the other Republicans pushing the carbon tax, for instance, would like it to replace Obama-era climate regulations.

But to be broadly popular, a carbon tax simply cannot be divorced from a broader left-populist economic agenda. To succeed politically, it will need to come in a broader package of policies, the net effect of which leaves most Americans better off.

As Paul argued: "The environment is something that, when we're born, each and every one of us has a common piece of ownership. And a tax and dividend policy restores that notion of common ownership."

Jeff Spross was the economics and business correspondent at TheWeek.com. He was previously a reporter at ThinkProgress.