The iPad is still the future

Lost amid the buzz about the HomePod and the high-end iMac Pro were some key changes to Apple's tablet

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

In the middle of Apple's Worldwide Developer Conference keynote this week, there was an almost audible sigh of relief. The company had just announced a forthcoming high-end iMac Pro, which will have a startling entry price of a cool $5,000. Despite the steep cost, though, it was nonetheless welcome. After unending complaints that Apple had abandoned the creative power users that made the company what it is, here was a new machine that finally got closer to what those loyalists wanted: a sleek, almost absurdly powerful traditional computer.

The news, accompanied by some minor upgrades to Apple's laptops, was significant less for what was shown, however, and more for when it was: early on in the keynote, and then quickly dispensed with. The message seemed clear. The Mac represents the past, and the updates to the line were there to please a small cadre of niche, if important, users. The middle of the show was thus the present. It focused on the iPhone, which still accounts for two-thirds of the company's revenue. But the final third of the keynote was mostly dedicated to the iPad. Despite the fact that it has become common to now hear that the iPad is dying a slow death, Apple ended with a new vision of that device as a real productivity machine, before closing with HomePod, Apple's competitor to the Amazon Echo and Google Home smart speakers. That sequence of events suggests a rather surprising turn of events: Those last two products, and the iPad in particular, represent not only just the future of Apple, but the future of mainstream computing itself.

If that sounds counterintuitive, it's because the narrative that the tablet is on its way down didn't emerge from nowhere. Despite massive success in the few years after its launch, iPad sales have dropped for the past 13 consecutive quarters, while tablet sales in general were down again in 2016. The reasons are straightforward: An old tablet still does the same things as a new one, making upgrades unappealing, and that early criticism of the iPad — that it's just a big iPhone — started to have even more relevance for tablets in general as phones got bigger and did more.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

The first iPad Pro was Apple's attempt to address this fact, but in truth, it did almost nothing a normal iPad couldn't do. It was merely faster, more easily attachable to a keyboard, and, at least in regards to the 13-inch model, bigger. Conversely, Microsoft, which originated the productive tablet category with its Surface line — it pioneered the all-important detachable keyboard that lets you do real work — presented a hybrid tablet that was in fact full computer, but still had the drawbacks of one: poorer battery life compared to a tablet, and the comparative clunky nature of full Windows. Neither were the ideal solution because they each had downsides that were too glaring, one lacking in some functionality, the other suffering from an excess of it.

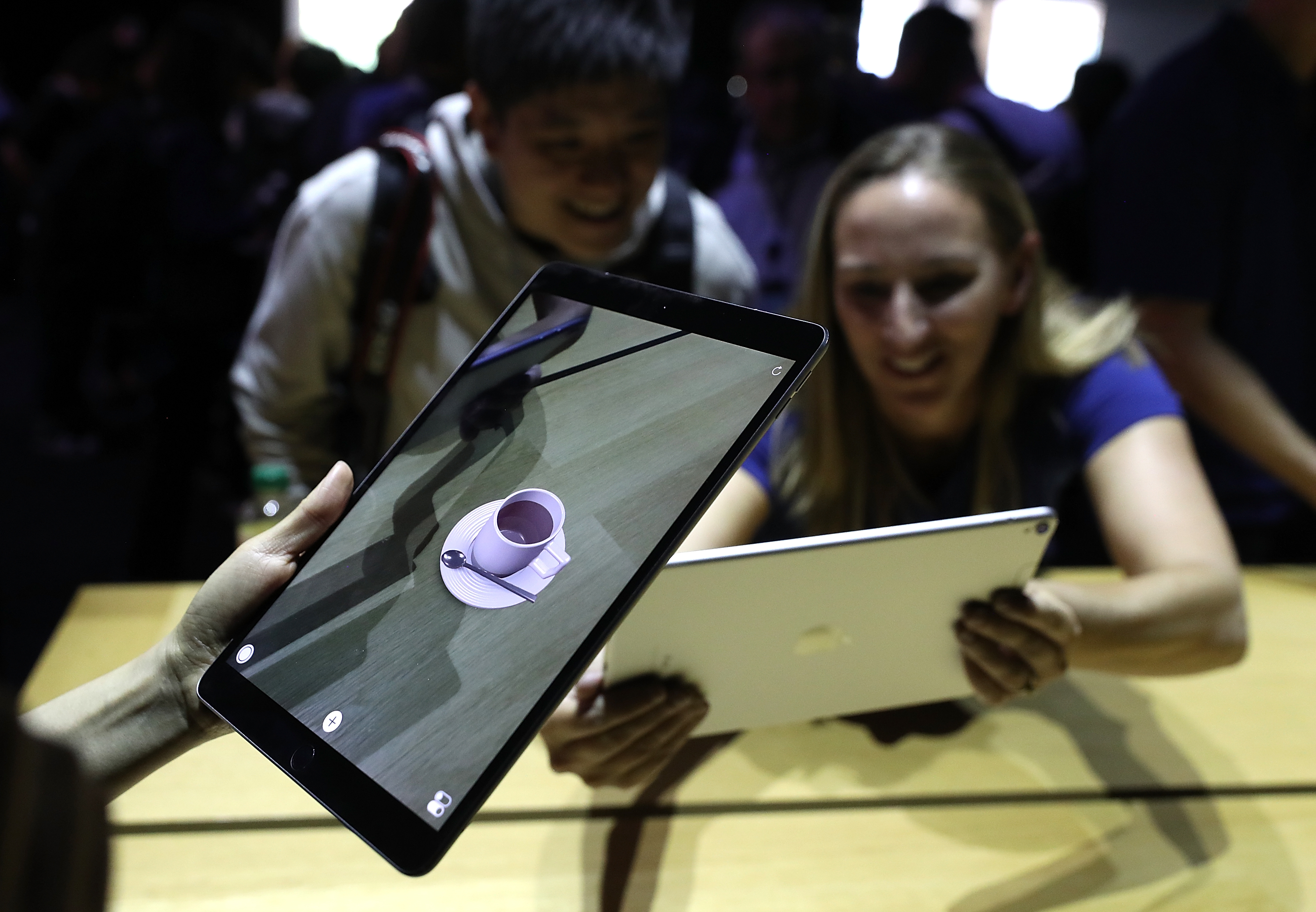

The news from WWDC this week changes that, though, because with iOS 11 (the software that runs iPhones and iPads) an iPad will soon be much better and viable for productivity. You'll be able to more easily run apps side-by-side, drag and drop things between, say, a photo app and your email, and also use a full-sized keyboard even on the smaller model. It will also let you quickly jump between what Apple calls spaces, which will allow a user to have, say, their to-do app and calendar just a swipe away. But because it is a mobile OS, apps open instantly and have a simplified yet still capable interface that makes real computing power vastly more approachable and user friendly.

In short, a tablet with a keyboard attached will do almost everything that most people need a computer do in a far simpler, intuitive, and faster fashion.

This matters because the seeming decline of the tablet unfortunately reinforced an outdated, obsolete narrative: that traditional PCs like MacBooks and Windows laptops are for real work, and touchscreen devices are for consumption. This is the story from commentators such as Paul Thurrott, the closest there is to a Microsoft enthusiast writer, who argues that without desktop apps, the iPad is merely a toy.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

But the iPad, along with other tablets, is the future of computing for most people — in part because the definition of computing is changing, but more importantly, because the real work most people do simply doesn't need a traditional computer. After all, what is the “real work” the vast majority of people do? They email a lot, do word processing, use basic spreadsheets and presentation software, touch up photos, make videos. All of those things can be done on a simple tablet like an iPad, and importantly, can be done more intuitively and easily there than on a traditional computer.

And it isn't just Apple who is filling that need. Google's Pixel tablets and other Android slates do much the same thing. Meanwhile, Microsoft is shifting its Windows software both to run on the same fast, quiet chips used in smartphones and tablets, and to function more like a tablet that only runs specific apps, thereby simplifying what was once too complex. It helps, too, that Microsoft and other companies have made their powerful productivity software like Office available and functional for tablets. In fact, all three major operating system makers are no longer competing over who can make the most powerful computer, but who can make the simplest, most user-friendly one.

It's that change which most clearly characterizes why the tablet is the future of computing. The shift to touchscreen smartphones has democratized computing in a way that PCs and Macs simply couldn't. The hybrid tablet functions as the right midpoint between a smartphone that is too small for many key tasks, and most laptops, which are too complex and large for what most people need.

This will surely sound like heresy to some, in part because power users are extremely vocal and influential online, and because many key media figures count themselves among that select group. Unfortunately, they have a tendency to not recognize themselves as niche users who are positively dwarfed by people with mainstream needs. What's more, one shouldn't get too utopian about the coming change. There is inevitably a kind of loss when one moves from an open operating system like MacOS or Windows, which allows for tinkering and customization, to one like iOS, which is almost completely closed.

But the tradeoff of that drop in abstract functionality is practical usability. A tablet with a keyboard attached is light and thin, and has much greater battery life than most laptops. More importantly, it is a computer for everyone: cheaper, simpler to use, and the future of computing. There will be another sigh of relief when this next, more user-friendly phase of computing arrives — but this time rather than heard emanating from a small group, it will instead be coming from the majority.

Navneet Alang is a technology and culture writer based out of Toronto. His work has appeared in The Atlantic, New Republic, Globe and Mail, and Hazlitt.

-

5 cinematic cartoons about Bezos betting big on 'Melania'

5 cinematic cartoons about Bezos betting big on 'Melania'Cartoons Artists take on a girlboss, a fetching newspaper, and more

-

The fall of the generals: China’s military purge

The fall of the generals: China’s military purgeIn the Spotlight Xi Jinping’s extraordinary removal of senior general proves that no-one is safe from anti-corruption drive that has investigated millions

-

Why the Gorton and Denton by-election is a ‘Frankenstein’s monster’

Why the Gorton and Denton by-election is a ‘Frankenstein’s monster’Talking Point Reform and the Greens have the Labour seat in their sights, but the constituency’s complex demographics make messaging tricky

-

The pros and cons of noncompete agreements

The pros and cons of noncompete agreementsThe Explainer The FTC wants to ban companies from binding their employees with noncompete agreements. Who would this benefit, and who would it hurt?

-

What experts are saying about the economy's surprise contraction

What experts are saying about the economy's surprise contractionThe Explainer The sharpest opinions on the debate from around the web

-

The death of cities was greatly exaggerated

The death of cities was greatly exaggeratedThe Explainer Why the pandemic predictions about urban flight were wrong

-

The housing crisis is here

The housing crisis is hereThe Explainer As the pandemic takes its toll, renters face eviction even as buyers are bidding higher

-

How to be an ally to marginalized coworkers

How to be an ally to marginalized coworkersThe Explainer Show up for your colleagues by showing that you see them and their struggles

-

What the stock market knows

What the stock market knowsThe Explainer Publicly traded companies are going to wallop small businesses

-

Can the government save small businesses?

Can the government save small businesses?The Explainer Many are fighting for a fair share of the coronavirus rescue package

-

How the oil crash could turn into a much bigger economic shock

How the oil crash could turn into a much bigger economic shockThe Explainer This could be a huge problem for the entire economy