The rise and fall of the Christian bookstore

Christian bookstores may well be destined for the history books

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

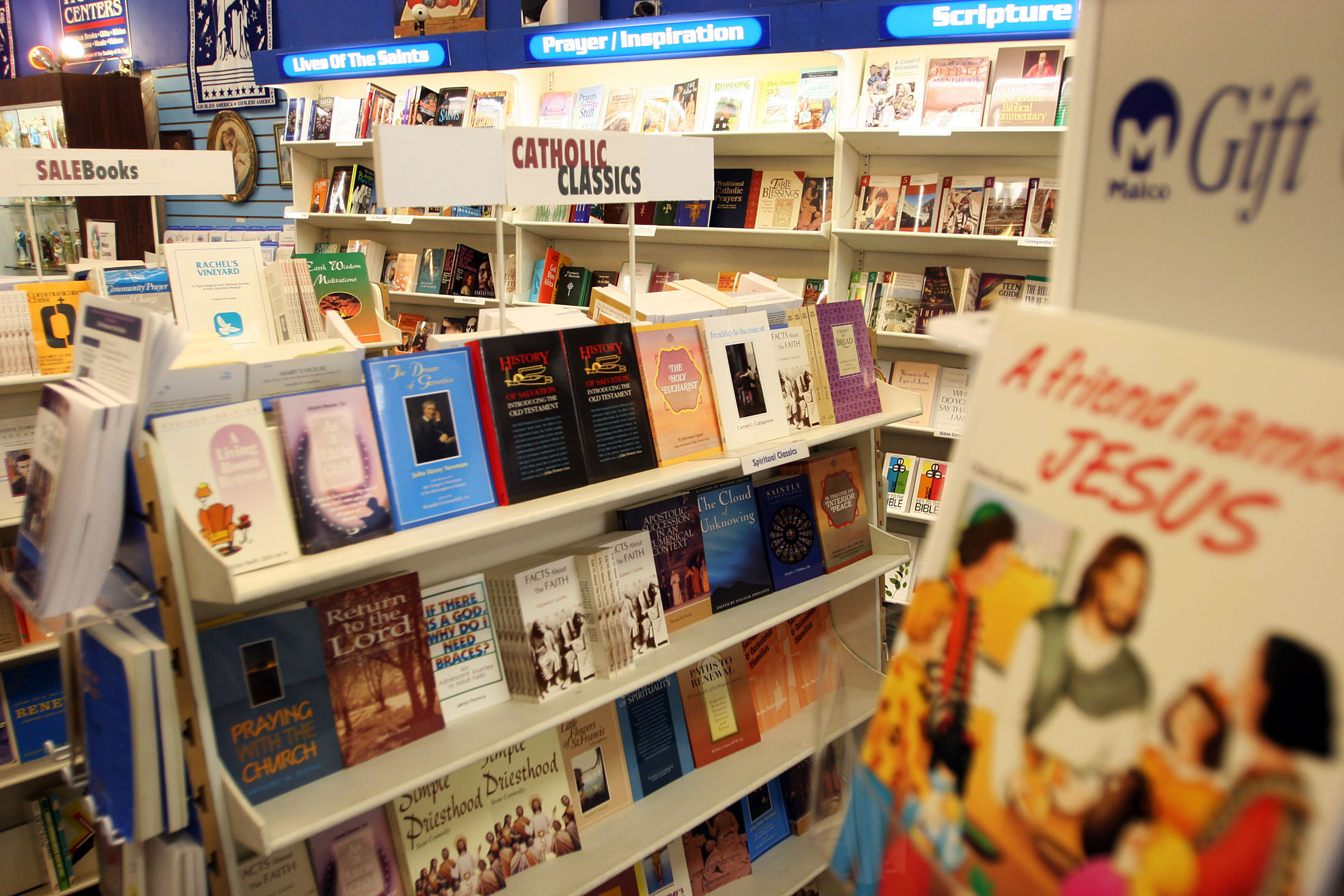

Back in the 1990s, it often seemed that every city and town in America had a strip mall with a Christian bookstore where you could purchase WWJD bracelets and enough devotional books to fill up the Ark of the Covenant. But today, these Christian bookstores are a dying breed. Indeed, it seems we are fast approaching an America where this particular brand of religious retailer will be no more than a memory.

Over the last decade, Christian bookstores across the nation have been shuttering. In some cases, consumers are just less interested in the stores' God-blessed inventory. But plenty of others are just opting to purchase religious items from online retailers, with Christian bookstores humbled before the same digital market forces that felled secular mom-and-pop bookstores.

The flailing Christian bookstore industry reached code red status earlier this year when Family Christian Stores, touted as "the world's largest retailer of Christian-themed merchandise," declared it would shutter all of its 240 stores across America and lay off 3,000 employees. The 85-year-old chain said that "changing consumer behavior and declining sales" left it no choice.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Given the state of the industry and larger retailing trends, Family Christian Stores' closure is seen by many as a harbinger of things to come. If trends persist, Christian bookstores may well be destined for the history books.

But Christian consumers should not let their hearts go troubled. This trend may turn out to be good news for the faithful.

Christian publishing has long been a presence in American life. But it was a renewed desire to evangelize the world following World War II that fueled the modern rise of Christian publishing, which focused mostly on Bibles and gospel tracts at the time. In 1950, the Christian Booksellers Association (CBA) formed in response to the growing need to connect and equip Christian product providers in the marketplace.

As time passed, religious retailers slowly spread across America and expanded their offerings. Then the industry truly exploded during the 1970s, and the Evangelical Christian Publishers Association (ECPA) was formed in 1974 to help give these new religious storeowners a chance to network and strategize.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

It's difficult to pinpoint exactly which cultural trend triggered the renewed interest in Christian content, but the American cultural revolution in the '60s and '70s seems like a plausible candidate. A perfect storm of progressive social change movements — from civil rights to feminism, anti-war protesting to environmentalism — swept across America. Many traditionalist Christians felt as if their religious values were under siege. In response, these believers mobilized and became more visible and vocal. The cultural unrest created an opportunity for printed content that spoke to these Christians' concerns and anxieties.

In 1970, Hal Lindsay's The Late Great Planet Earth rocked the marketplace with claims that the biblical end of the world was fast approaching. Bantam picked up the title in 1973, making it the first Christian prophecy book released by a secular publisher, and it went on to sell more than 30 million copies. The Living Bible was the bestselling non-fiction title of 1972 and 1973, and Billy Graham's Angels was the bestselling non-fiction title of 1975. The mainstream success of books like these proved that a hungry market of religious readers existed in America.

The trend continued to build. In December 1983, an Associated Press article titled "Christian book sales are booming" relayed that Christian booksellers had grown by 20 to 25 percent over the past decade.

As Sue Smith, president of CBA notes, industry growth continued into the '90s thanks to several breakout bestsellers. "People who would never walk into a Christian store suddenly would come in for The Prayer of Jabez, The Purpose Driven Life, and the Left Behind series," she says. Each of these titles became #1 New York Times bestsellers.

In the late '90s, however, the advent of the digital age began to transform the way Americans shopped and consumed media. The rise of online retailers created stiff competition for brick-and-mortar stores. The absence of rent, real estate, and large staffs allowed these emerging distributors to offer deep discounts that traditional booksellers simply could not match. The internet also created options for authors to affordably self-publish their work and distribute it straight to consumers. This, combined with a sharp decline in book sales generally and the rise of reduced price e-books, ate into publishers' profits.

These converging trends decimated the print publishing industry. And retailers, which form the industry's front line, bore the brunt of it. Many prominent chains, such as Borders, B. Dalton, and Waldenbooks, floundered and eventually folded. Others, including industry giant Barnes & Noble, teetered on the brink of bankruptcy.

Religious chains faced even more harrowing circumstances than their larger secular cousins. In addition to the transformation of media, the American religious landscape was shifting rapidly. According to Gallup, church attendance and religiosity declined during the '90s and early 2000s. Americans identifying as non-religious rose during this period. As younger Christians came of age, they found themselves less interested in the American Christian subculture and its institutions. Demand for religious books fell, and the once healthy Christian marketplace hemorrhaged.

By the earliest part of the 21st century, the Christian publishing industry was in major trouble. Christian publishers struggled to stay afloat, and religious retailers were taking on water. The once-booming CBA, which boasted 3,000 members and approximately 4,000 Christian retail stores in the mid-'80s, had dwindled to 1,813 members and 2,800 stores by 2008. More than 300 Christian retailers closed in 2005 alone.

With the shuttering of Family Christian Stores this year, only a couple of sizeable chains and a smattering of independents remain. We may be witnessing the dawning of the last days for these once vibrant institutions.

But here's the real shocker: The demise of Christian bookstores may actually be good news for American Christianity itself.

If you've visited a Christian bookstore lately, you might have noticed that they traffic in much more than just books. As the market contracted, the diversity of inventory expanded to include products with higher profit margins. Shelves are filled to overflow with a range of religious home décor, toys, music, and clothing designed to appeal to spiritual shoppers. You'll find inspirational figurines, Bible-themed Monopoly-style board games, automobile decals, and even religious breath mints.

Christian kitsch can help retailers pay the rent. But the "trinketization of Christianity" has plastered a cheap face onto a rich religious movement with a more than 2,000-year history. Purging these items from the marketplace helps strip the consumerist veneer off the faith.

The disappearance of Christian retailers will also likely improve the quality of religious books. Christian authors can no longer be the strongest voice in their small religious pond. Beating out the quarter's best niche devotional will no longer suffice. Authors will now have to compete with Chabon and Patchett, Franzen and Friedman.

"We're seeing that the stiff competition in the general market requires that you publish Christian books with quality writing," as Stan Jantz, head of the Evangelical Christian Publishers Association, notes. "Because the bar is being raised, there is a real desire among Christian publishers to find quality writing right now."

Competing in a broader marketplace will also require a broader diversity of religious content. Christian retailers have often curated their inventory based on their theological leanings. For example, Lifeway Christian Stores requires authors to adhere to the beliefs of the Southern Baptist Convention, the denomination that owns the chain. If an author supports gay marriage, doesn't interpret the Bible in strictly literal ways, or supports the equality of women in church leadership, they will be banned from Lifeway's shelves. As these retailers disappear, there will no longer be gatekeepers policing the market with the same rigor. And this may plow the ground for fresh and even risky theological reflections.

These three developments — the purging of religious kitsch, better quality prose, and a greater diversity of ideas — means the loss for retailers is a gain for readers. Hallelujah.

Jonathan Merritt is author of the book Learning to Speak God from Scratch: Why Sacred Words are Vanishing — and How We Can Revive Them and a contributing writer for The Atlantic.