How Murder on the Orient Express murders Agatha Christie

At least it's pretty?

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Kenneth Branagh's Murder on the Orient Express might be 2017's prettiest cinematic misfire. The remake — which boasts a formidable cast, including Derek Jacobi, Dame Judi Dench, Michelle Pfeiffer, Penelope Cruz, and Leslie Odom, Jr. — is exquisitely filmed cardboard. Its jokes flail. Its pathos amuses. The film that should have it all — luxury, intrigue, murder, deceit — is lachrymose, listless, and (given how satisfying a mystery this famously is) disappointingly light on detection. Instead of meticulously matching clues to revelations, it turns Hercule Poirot, Agatha Christie's famous detective, into an unappealingly emotional Holmes.

The setup of Christie's most famous bottle episode, if you don't know it, is pretty simple: Poirot boards the Orient Express in the dead of winter, hoping for a respite before he starts on his next case. To his surprise, the train is full. Among the passengers is a rather sinister individual named Ratchett (played here by Johnny Depp). He tells Poirot his life is in danger and tries to hire him for protection. Poirot refuses, the train hits a snowdrift, and Ratchett is murdered overnight. No one could have done it but the folks on the train, and a fascinating study of the passengers on board ensues.

Sidney Lumet's 1974 Murder on the Orient Express was — like Clue, which in some ways parodied it — both sumptuous and understated, cozy and threatening, equal parts thrilling and dry and absurd. It, too, had an all-star cast, with Albert Finney as Poirot and turns from the likes of Vanessa Redgrave, Ingrid Bergman, Sean Connery, Lauren Bacall, and Jacqueline Bisset. If you've seen the film, you likely remember the moment when Wendy Hiller started to crack a wry, crooked smile as the formidable Princess Dragomiroff. It's a moment that captures the film's tone exactly. The famous mystery poses an interesting moral challenge — what if the murder victim is an awful person? — and works it through as Agatha Christie often did: drily, methodically, modeling Poirot's clinical interest even as it exposed everyone else's silliness by comparison. Lumet's film was clean and quick and crisp. Branagh's is (like his Poirot) ponderous, a tear-soaked water cracker.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

The new Orient Express is very pretty, though its width expands and contracts depending on the production's needs. The same might be said of its characters: The script alters several for no clear reason. Poirot — who has always been amusingly fussy and effete, with his extravagant moustache, dyed whiskers and hair — is greying and definitely straight in this production, and not just straight but in love with a dead woman with whose photograph he mournfully communes. His insistence on symmetry and perfection in the attire of others is retconned here into a depressing form of OCD — this Poirot is tortured, you see. Taking a page from Monk, the world is a torment to him. So much for Christie's Poirot, who was always a discerning bon vivant, endlessly amused by the humans he observes.

The grey of Branagh's (truly impressive) whiskers isn't actually meant to age him, as his Poirot is startlingly athletic. If Agatha Christie's Poirot famously scorned Sherlock Holmes for scurrying needlessly about analyzing cigarette ash when the “little gray cells” of the brain could do the necessary work, Branagh's is tramping across the roofs of train cars and chasing bad guys. Christie's Poirot likes his interiors ludicrously overheated; Branagh's elects to picnic in a snowscape.

There are other changes — the Greek doctor is combined with Colonel Arbuthnot to make “Doctor Arbuthnot,” a black doctor in an interracial relationship in 1934. An Italian chauffeur was made Latino, and Mrs. Hubbard — the fussy loud American mother of the novel, who went on and on about her daughter and bored everyone around her — has been downgraded into a much less tiresome (and funny) cougar. Structurally, the point of this character is that she's over the top. It's unclear what Michelle Pfeiffer's function is supposed to be; she's much too attractive for her sexual overtures to scan as either funny or tiresome.

This is minor, but as a Christie completist, I was especially irked to see Penelope Cruz's character (based on Ingrid Bergman's Swedish missionary Greta Ohlsson) renamed “Pilar Estravados.” This, fellow fans will know, is a character from another Agatha Christie novel, A Holiday for Murder. But why? She doesn't seem to be commenting on the character; this isn't an exciting crossover appearance. The only reason to recycle the name seems to be that Cruz is … also Spanish?

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Some of the changes work. Depp is quite good at playing a horrible man whose departure no one much minds, and Josh Gad makes some interesting choices as Hector MacQueen, his secretary. Willem Defoe is great when he's onscreen; so is Daisy Ridley. The trouble isn't the acting; it's that their scenes don't accomplish much. They could! In fact, one of the most interesting new scenes — in which Ridley pours a red wine into a white — turns out in retrospect to have been a very nice piece of theater. But the film doesn't really enjoy it. As a director, Branagh has trouble going back to all the guns he's placed on the mantle. A number of clues that were pivotal in the original film and in the novel show up here only to go unmentioned when the mystery is finally solved.

Neither the cast nor the camera can save this unfocused effort. Murder on the Orient Express boasts lovely cinematography, mediocre writing, absurd musical cues, baffling melodrama, and a luminary cast offering performances that dither in search of a point.

Lili Loofbourow is the culture critic at TheWeek.com. She's also a special correspondent for the Los Angeles Review of Books and an editor for Beyond Criticism, a Bloomsbury Academic series dedicated to formally experimental criticism. Her writing has appeared in a variety of venues including The Guardian, Salon, The New York Times Magazine, The New Republic, and Slate.

-

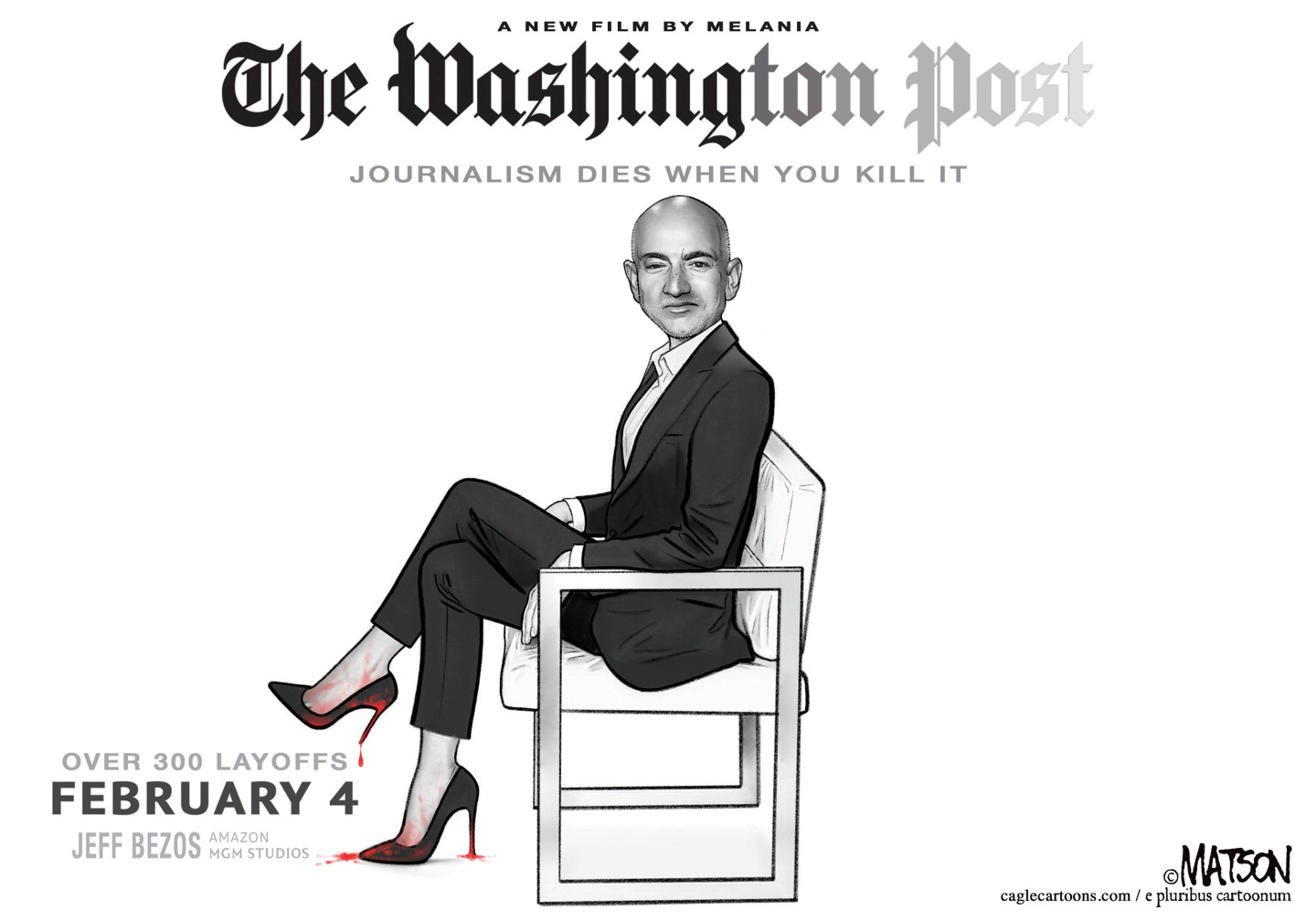

5 cinematic cartoons about Bezos betting big on 'Melania'

5 cinematic cartoons about Bezos betting big on 'Melania'Cartoons Artists take on a girlboss, a fetching newspaper, and more

-

The fall of the generals: China’s military purge

The fall of the generals: China’s military purgeIn the Spotlight Xi Jinping’s extraordinary removal of senior general proves that no-one is safe from anti-corruption drive that has investigated millions

-

Why the Gorton and Denton by-election is a ‘Frankenstein’s monster’

Why the Gorton and Denton by-election is a ‘Frankenstein’s monster’Talking Point Reform and the Greens have the Labour seat in their sights, but the constituency’s complex demographics make messaging tricky

-

Walter Isaacson's 'Elon Musk' can 'scarcely contain its subject'

Walter Isaacson's 'Elon Musk' can 'scarcely contain its subject'The latest biography on the elusive tech mogul is causing a stir among critics

-

Welcome to the new TheWeek.com!

Welcome to the new TheWeek.com!The Explainer Please allow us to reintroduce ourselves

-

The Oscars finale was a heartless disaster

The Oscars finale was a heartless disasterThe Explainer A calculated attempt at emotional manipulation goes very wrong

-

Most awkward awards show ever?

Most awkward awards show ever?The Explainer The best, worst, and most shocking moments from a chaotic Golden Globes

-

The possible silver lining to the Warner Bros. deal

The possible silver lining to the Warner Bros. dealThe Explainer Could what's terrible for theaters be good for creators?

-

Jeffrey Wright is the new 'narrator voice'

Jeffrey Wright is the new 'narrator voice'The Explainer Move over, Sam Elliott and Morgan Freeman

-

This week's literary events are the biggest award shows of 2020

This week's literary events are the biggest award shows of 2020feature So long, Oscar. Hello, Booker.

-

What She Dies Tomorrow can teach us about our unshakable obsession with mortality

What She Dies Tomorrow can teach us about our unshakable obsession with mortalityThe Explainer This film isn't about the pandemic. But it can help viewers confront their fears about death.