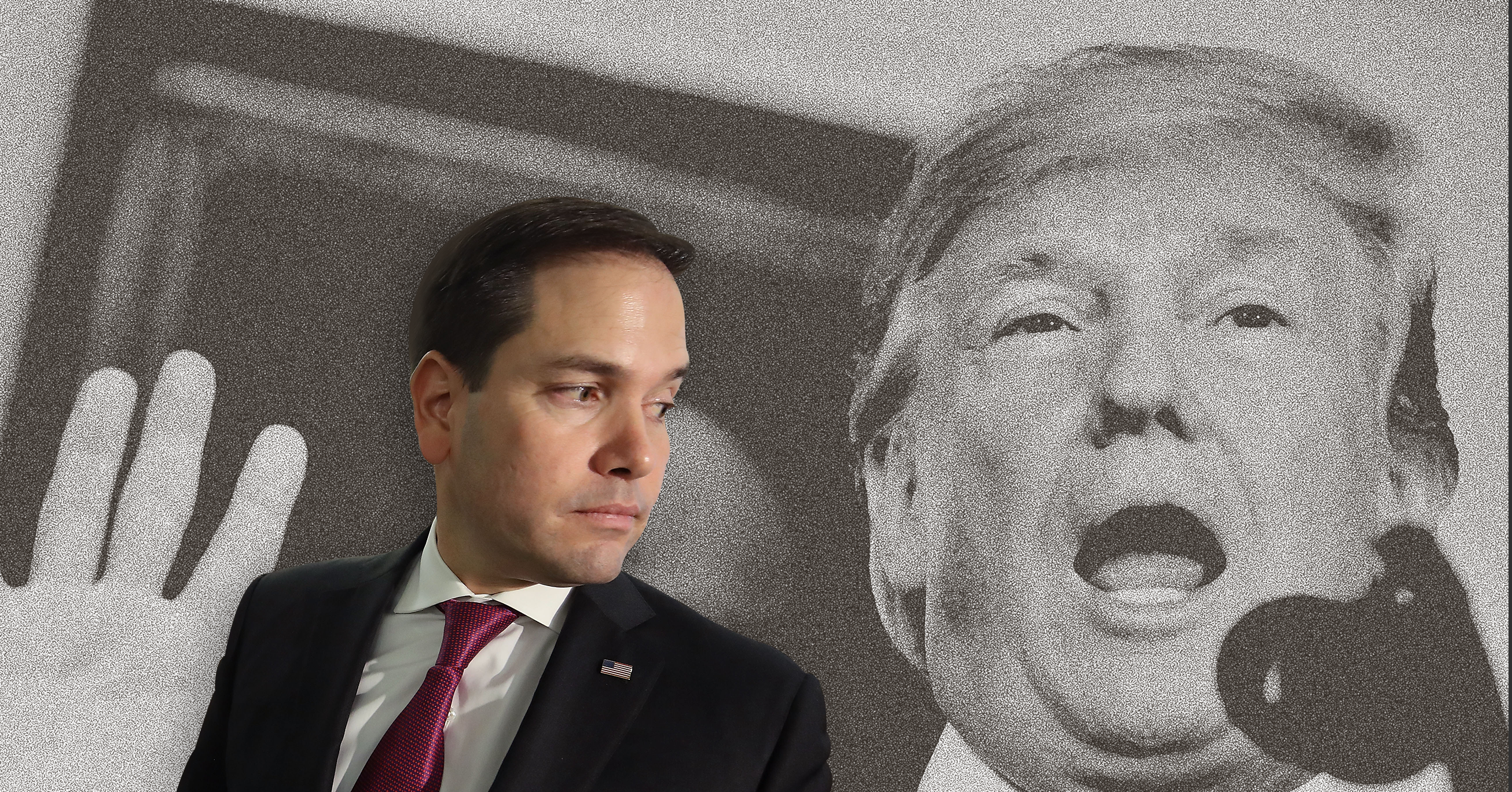

Rubio's recurring Trump nightmare

Will the junior senator from Florida ever escape his bête noire?

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

It's hard out there for a reasonable Republican.

If you are such a person, you've no doubt spent many an hour looking ahead to the time when Donald Trump leaves office, either in 2021 or 2025, and your party begins the next phase of its history. Will the GOP leave the Trump era behind like a bad dream? Will the base demand continued fealty to the 45th president? How will the choices you made hold up? Will you be able to live with the compromises you made? Where is the sweet spot with the perfect combination of party loyalty, ideological consistency, and principled integrity, and did you find it soon enough to plant yourself there?

I'd like to consider these questions through the dilemma of one of the party's most complicated politicians, Florida Sen. Marco Rubio. In the last few weeks, Rubio has become the target of a great deal of ire from a difficult source to strike back at: the students from Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland. "I'm going to start off by putting this price tag right here," said David Hogg as he began his speech at the March For Our Lives in Washington, "as a reminder for you guys to know how much Marco Rubio took for every student's life in Florida. $1.05." That represents the amount of support Rubio has gotten from the National Rifle Association ($3.3 million) divided by the number of students in Florida (3.1 million). Other students wore the price tags, too. They could have gone after their governor, the odious Rick Scott, who also has a long history of NRA patronage, but instead they chose Rubio, perhaps exactly because they expect more from him.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

It was brutal, particularly given that Rubio, more than other politicians, has made an attempt to have a dialogue about the issue. He appeared at a CNN town hall where he was harshly questioned by some of those same students, and said he would support raising the minimum age to buy a rifle to 21 and was reconsidering his opposition to a ban on high-capacity magazines.

But it wasn't enough to convince the students that he'd really be their ally, particularly when he brushed off a question about all the support he's gotten from the NRA. That is, in many ways, Rubio's story: A guy whose good intentions only occasionally match up with his actions, and whose spectacular promise has again and again been undercut by not just Donald Trump himself, but all Trump signifies about the Republican Party.

As beleaguered and even pathetic as Rubio can sometimes seem, it was just a few short years ago that he was widely believed to be the party's future, a talent so incandescent that he was destined not only to become president but to drag the party of old white folks into the 21st century behind him. He wasn't just smart and articulate and persuasive, he was everything cool the GOP wasn't: young, bilingual, listens to hip-hop, someone who could translate conservatism to the next generation. Time magazine described him as "the charismatic conservative often hailed as the Tea Party's answer to Barack Obama" in a cover story that called him "The Republican Savior."

Then it all went sour. The first time he should have realized there was something terribly wrong was when he participated in the Gang of Eight, a bipartisan group that wrote a comprehensive immigration bill that passed the Senate in 2013 but went nowhere in the House. For his hard work and sincere effort to solve a serious problem, Rubio was excoriated on conservative talk radio and all but excommunicated from the Tea Party.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

He ran for president anyway — and ran into not only Donald Trump, but the party that produced him. Over the course of an increasingly sad 2016 campaign, Rubio obviously realized that Republican voters just weren't buying what he was selling. The most revealing moment of the primaries came when he aired an ad in which this fresh-faced man of the future said, "This election is about the essence of America, about all of us who feel out of place in our own country." Us? The whole point of Marco Rubio is that he doesn't feel out of place in the new America. At least that's what it was supposed to be.

But he probably feels out of place now. It's not that Rubio has any ideological objection to anything the Trump administration is doing, because it's been consistently conservative and Rubio is himself extremely conservative. But he isn't going to be one of those rare Jeff Flake-types, who offer unrestrained criticism of Trump's erratic governing style and personal repugnance on their way to retirement. Rubio is only 46, and he'll almost certainly be running for president again in 2024. He knows as well as anyone that he'll need to win those Trump voters over.

Yet he's also a politician who would like to have wide appeal, and clearly wants to show how reasonable and open-minded he can be. If he were a columnist instead of a senator, he might well be one of the "Never Trump" crowd, those conservatives who maintain for reasons of ideological purity or commitment to propriety that they simply will not tolerate this vulgarian president. Those media figures, whether more toward the center or more to the right, will emerge from the Trump era in terrific shape, their ideological commitment intact and their stature elevated by liberals always looking for reasonable conservatives they can talk to.

Some of those columnists, like Ross Douthat and Matt Lewis, have rushed to Rubio's defense, arguing that he's being excoriated despite being more willing to consider compromise than other Republicans. "In a different world maybe you could make deals with a Republican like Rubio," laments Douthat; "in this world with this G.O.P., you can work with him only if you're clearly the one forcing him to the table, and ultimately that's just a means to the real goal of his eventual defeat."

Which may well be right, and it's hard to see how Rubio can find a way out of his dilemma. When Donald Trump leaves office, Rubio will no doubt tell himself that he made the best he could of a terrible situation. But he may find that he can't escape Trump and Trumpism, and when he runs for president again he'll be both too far from Trump for the GOP base and too close to him for the general public.

If it's any consolation, a lot of other Republicans will have the same problem.

Paul Waldman is a senior writer with The American Prospect magazine and a blogger for The Washington Post. His writing has appeared in dozens of newspapers, magazines, and web sites, and he is the author or co-author of four books on media and politics.

-

Quentin Deranque: a student’s death energizes the French far right

Quentin Deranque: a student’s death energizes the French far rightIN THE SPOTLIGHT Reactions to the violent killing of an ultra-conservative activist offer a glimpse at the culture wars roiling France ahead of next year’s elections.

-

Secured vs. unsecured loans: how do they differ and which is better?

Secured vs. unsecured loans: how do they differ and which is better?the explainer They are distinguished by the level of risk and the inclusion of collateral

-

‘States that set ambitious climate targets are already feeling the tension’

‘States that set ambitious climate targets are already feeling the tension’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?Talking Point Peter Thiel and Larry Page preparing to change state residency

-

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one report

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one reportIN THE SPOTLIGHT By blocking an approved segment on a controversial prison holding US deportees in El Salvador, the editor-in-chief of CBS News has become the main story

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June

-

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardon

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardonTalking Point Convicted sex trafficker's testimony could shed new light on president's links to Jeffrey Epstein

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred