Is the G7 obsolete?

The G7 no longer comprises the world's most powerful economies. So what does it do?

Today and tomorrow, the leaders of the Group of Seven will meet in Quebec, Canada, for their annual summit. Comprised of America, France, Germany, the United Kingdom, Japan, Canada, and Italy, the G7 and its annual statements of purpose have become synonymous with international power and cooperation. But today, many G7 members are playing second fiddle on the world stage. In a symbol of its own declining relevance, the group may end the 2018 summit without any joint statement at all.

Is the G7 obsolete?

The group began in the 1970s. While America still remained at the top of the economic world order, the end of the Bretton Woods system brought a new need for international cooperation to manage trade and exchange rates. Inflation was becoming a problem, as were oil embargoes from OPEC. One clear example of the G7's importance came in the 1980s, when the Reagan administration successfully negotiated a lower value for the U.S. dollar with France, Britain, Japan, and Germany. That deal closed a looming American trade deficit and headed off the threat of Trump-style tariffs.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

For a while, the G7 could be crudely understood as a cooperative body allowing the globe's seven biggest economic powerhouses (or something close to its seven biggest) to coordinate and talk out problems. But in recent decades, the global economic order has changed dramatically. Adjusted for purchasing power parity, China's economy is now the biggest in the world. India outranks everyone in the G7 but America. Russia, Brazil, and Indonesia are bigger than four of the seven. Mexico, Turkey, Saudi Arabia, and more are ahead of Canada. "We no longer expect a significant message [out of the G7] that will design the course of the world economy," Grzegorz Kolodko, an economics professor and former Polish finance minister, told The Week.

Then there's the alternative Group of Twenty, which includes all the members of the G7 as well as many of the economic powers listed above. In fact, it's more like the G43, as one of the 20 is actually the European Union. (Which also sends leaders to the G7 as a kind of junior member.) "I think the meaning of the G7 will decline as the world gradually moves towards G20," Kolodko continued. "And I think that's much better, because the G20 is much more representative of the world economy."

That said, while the G7 has lost its role as the representative club of world economic power, that doesn't necessarily mean it's outlived its usefulness. The G7 still represents the world's most powerful Western democracies. Thanks to those similarities, its members still have plenty of issues and strategies they need to hash out among themselves, before bringing the matter to the world stage.

"It's really useful for advanced democracies to have a space — unlike the World Trade Organization, unlike the Security Council — where they can have frank conversations about challenges of authoritarianism and state capitalism and development aid without being out-voted or vetoed," political scientist Todd Tucker, who focuses on global economic governance at the Roosevelt Institute, told The Week.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

For instance, while the United States still has some trade and exchange rate issues with other G7 members, its big problems these days are with China. Yet America's trade and exchange rate gripes with China are also other G7 nations' gripes with China. So the U.S. will need the group's help in responding. Cooperation among G7 members was also crucial to developing the Paris Agreement to combat climate change, and the international deal with Iran to roll back that country's nuclear program. These countries still largely run other crucial economic institutions like the International Monetary Fund. And they will also need to talk among themselves about North Korea, before bringing other powers like China into the conversation.

But this gets us to the other problem facing the G7: its own growing internal divisions.

The obvious elephant in the room here is President Trump. He's threatened the viability of the Paris accord and the Iran deal by pulling the U.S. out of both. His recent tariffs on steel and aluminum have angered the other G7 members and thrown a wrench into their ability to cooperate on broader matters like China. All of these issues will be on the table at this year's summit, and Trump's bomb-throwing is largely why little significant headway is expected. German Chancellor Angela Merkel was reportedly so distraught by Trump's election that it convinced her to run for a fourth term.

Yet the reactionary nationalism that Trump represents is looming in other G7 members as well. France and Germany are contending with their own right-wing factions. Britain is going through Brexit. And a new Italian government, combining two anti-establishment parties of the right and left, has just survived a confrontation with the eurozone. "Half of the [G7] membership is dealing with executive branch populism; much of the rest of it is dealing with near misses," Tucker said. "So these economies no longer only face similar economic challenges, but also political ones."

Nor is this rising nationalism some freak disaster that has befallen a blameless G7 leadership. Fiscal austerity and tight money policies enforced by the eurozone — which is, to say, largely enforced by Merkel's Germany — have decimated Greece, done serious harm to Italy, and led to a general economic stagnation across Europe. America and Britain have similar self-inflicted economic wounds, and the global trade and free capital movement pushed by G7 powers helped wreck much of their own working class. If right-wing nationalism is a disease that must be cured, it is also a disease these choices allowed to fester and spread.

The Group of Seven will almost certainly never return to its former station and glory. But it arguably still has a critical role to play in global affairs.

Whether it can fulfill that role depends largely on understanding and correcting its own mistakes.

Jeff Spross was the economics and business correspondent at TheWeek.com. He was previously a reporter at ThinkProgress.

-

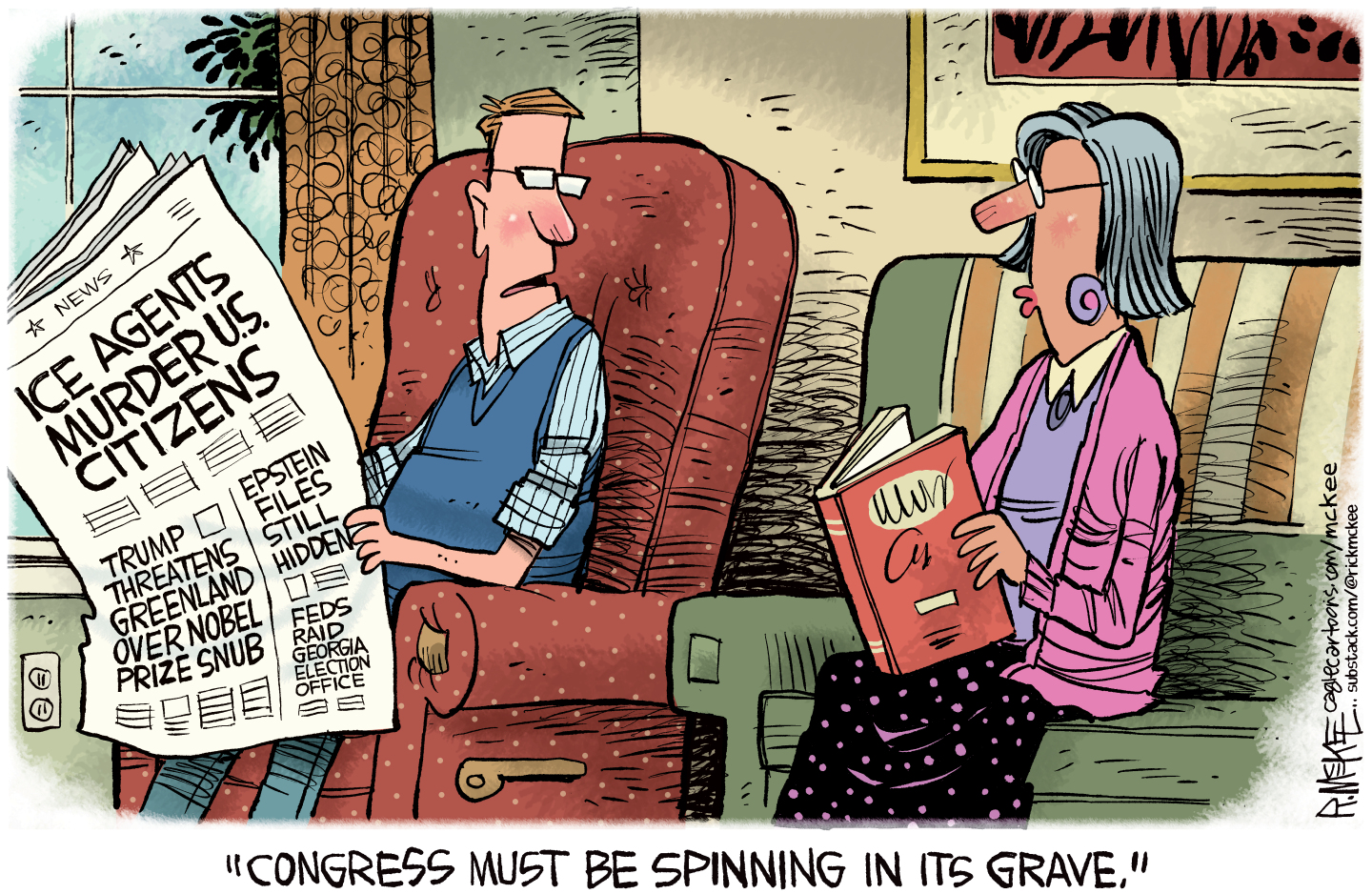

Political cartoons for January 31

Political cartoons for January 31Cartoons Saturday's political cartoons include congressional spin, Obamacare subsidies, and more

-

Syria’s Kurds: abandoned by their US ally

Syria’s Kurds: abandoned by their US allyTalking Point Ahmed al-Sharaa’s lightning offensive against Syrian Kurdistan belies his promise to respect the country’s ethnic minorities

-

The ‘mad king’: has Trump finally lost it?

The ‘mad king’: has Trump finally lost it?Talking Point Rambling speeches, wind turbine obsession, and an ‘unhinged’ letter to Norway’s prime minister have caused concern whether the rest of his term is ‘sustainable’

-

The pros and cons of noncompete agreements

The pros and cons of noncompete agreementsThe Explainer The FTC wants to ban companies from binding their employees with noncompete agreements. Who would this benefit, and who would it hurt?

-

What experts are saying about the economy's surprise contraction

What experts are saying about the economy's surprise contractionThe Explainer The sharpest opinions on the debate from around the web

-

The death of cities was greatly exaggerated

The death of cities was greatly exaggeratedThe Explainer Why the pandemic predictions about urban flight were wrong

-

The housing crisis is here

The housing crisis is hereThe Explainer As the pandemic takes its toll, renters face eviction even as buyers are bidding higher

-

How to be an ally to marginalized coworkers

How to be an ally to marginalized coworkersThe Explainer Show up for your colleagues by showing that you see them and their struggles

-

What the stock market knows

What the stock market knowsThe Explainer Publicly traded companies are going to wallop small businesses

-

Can the government save small businesses?

Can the government save small businesses?The Explainer Many are fighting for a fair share of the coronavirus rescue package

-

How the oil crash could turn into a much bigger economic shock

How the oil crash could turn into a much bigger economic shockThe Explainer This could be a huge problem for the entire economy