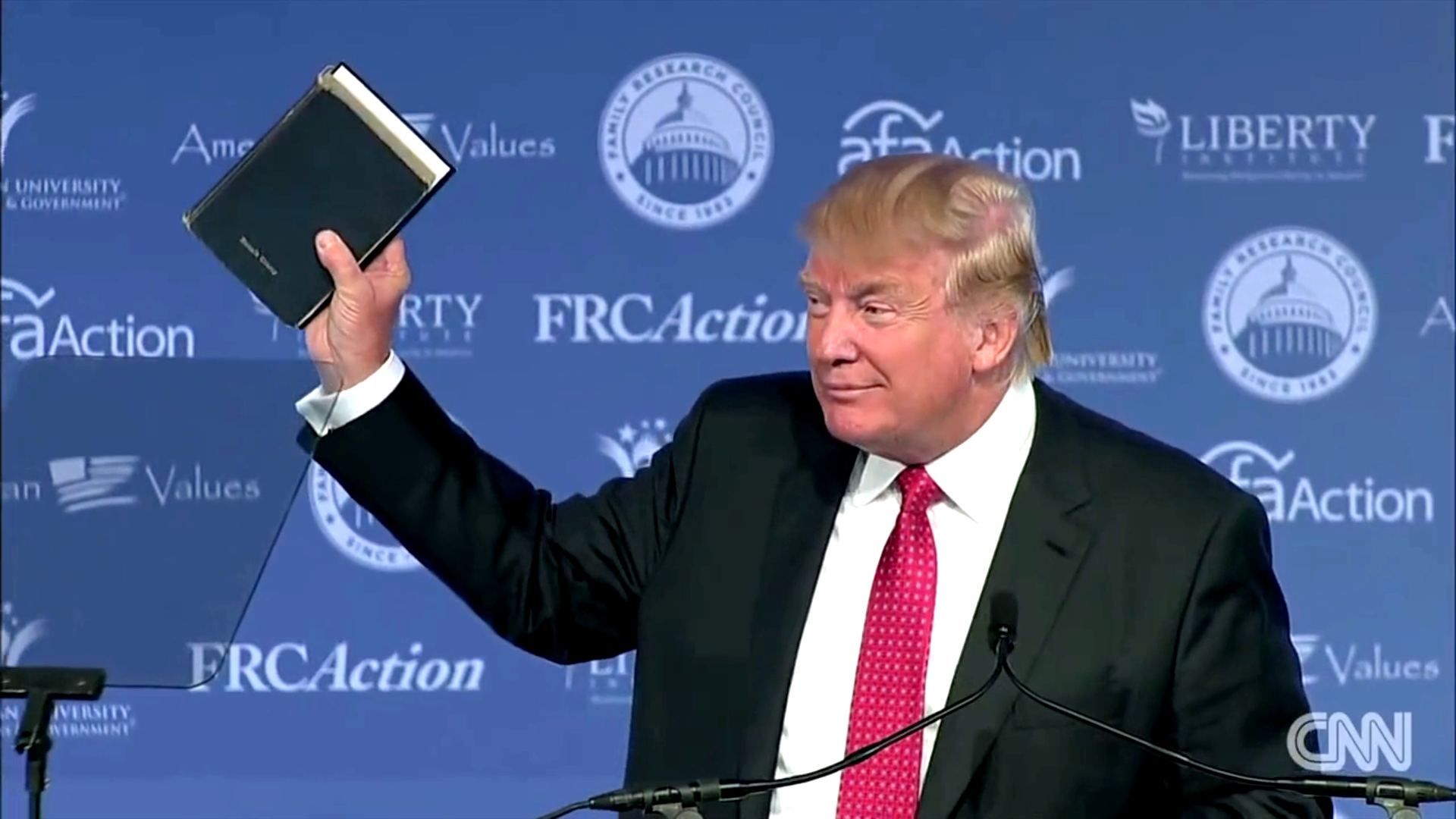

President Trump and the evangelical lust for power

Why do the religiously devout so readily kneel before this profane charlatan?

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

"I was raised in an evangelical congregation, and today still consider myself a Christian," says filmmaker Christopher Alan Maloney in the opening sequence of In God We Trump. "But no matter how hard I tried, I just couldn't imagine my Sunday School teacher or youth pastor casting their vote" for someone like President Trump.

I could say the same, except I have actively avoided wondering how some of those beloved figures from my childhood voted in 2016. It is one thing to hear that infamous statistic, that 81 percent of white evangelicals who voted backed Trump, and to consider it from the broad, socio-theological view of analysis. It is another thing entirely to confront the possibility that the people who shaped your own ethics, not by their words alone but by their very lives, could have discarded that example at the ballot box.

For many current and former evangelicals, this enthusiasm for Trump has been an apocalypse — literally, a revealing. It has fostered disillusionment and a low hum of grief. "The inner conflict I can never quite reconcile these days," mused author D.L. Mayfield on Twitter, is how "a community now revealed to be obsessed with power introduced me to Jesus, the one who willingly lays down his life and pursues the poor, the sick, and the oppressed." If I have escaped much of this conflict, it is only because previously established distance — theological, political, geographic — chanced to put me farther from the bomb when it went off.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

And so the question Maloney’s documentary explores — how and why American evangelicals could so enthusiastically back a politician who incarnates the ethical failings they decry — is a nagging one. It has been endlessly examined since the election, and this cottage industry has yet to show signs of dying off. This new contribution to the conversation meditates in synecdoche, hearing as much from experts as from ordinary people, former evangelicals still shell-shocked over how their people helped President Trump win.

In God We Trump, which will be available on iTunes and Amazon beginning Oct. 17, finds its strength in its ex-insider's critique of white evangelicalism's hypocrisy, quest for power, and confusion of the kingdom of heaven with American empire. Maloney has catalogued a horrifying array of clips from Trump-supporting preachers, who in the run-up to the election made spiritual abuse a get-out-the-vote technique. "You're gonna be held seriously, seriously to account by God if you don't vote," snarls televangelist Kenneth Copeland. "You're gonna be guilty of murder. You're gonna be guilty of an abomination of God. You're gonna be guilty for every baby that's aborted from this election forward."

Copeland's prosperity gospel puts him on the fringes of evangelicalism, but where Trump is concerned he reflected a growing but shameful consensus. Part of the reason the president's success among white evangelicals came as such a surprise, In God We Trump posits, is that many would not admit their support before he won. "There was that hidden evangelical vote, people not wanting to admit they were voting for Trump," says the sycophantic pastor Robert Jeffress in a Fox Business appearance, sharing an anecdote about elderly church ladies who backed Trump but "were afraid to tell anybody."

That fear strikes me as a source of hope, for shame can be a sign of a functioning conscience. As Mayfield wrote, quoting a friend, "evangelicals told us the truth, and they told us a lie." Perhaps, somewhere, they remember the truth that character matters; that we cannot serve two masters; that our citizenship and security is found in Christ, not Washington; that it is possible to gain the White House and lose your soul.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Maloney's film is weaker in its examination of its own assertions and assumptions. For example, several speakers claim Trump's 2017 religious liberty executive order ended the Johnson Amendment's ban on churches endorsing political candidates while retaining 501(c)(3) nonprofit status. In reality, the order merely urged the IRS to prioritize other enforcement. After initially threatening suit, the ACLU determined the order had "no discernible policy outcome." They did not bother to sue, and Trump's subsequent request that the GOP-held Congress officially nix the amendment was ignored. Despite Jeffress' hopes and In God We Trump's interviewees' fears, the Johnson Amendment and other bulwarks of public secularity remain intact.

At a larger scale, In God We Trump does not dramatically diverge from the meta-structure of church-state relations assumed within white evangelicalism. It simply furnishes it with different convictions.

Both camps function within a messy hybrid of what we might call transformationalism — a belief that Christians should use political power to make the state and society conform to God’s will for humanity — and dualism — a belief that church and state are separate kingdoms, designed for different work and suited for different behavior.

For Trump supporters, transformationalism ignores the Apostle Paul's directive against holding non-Christians to Christian moral commitments and produces calls to make America a "Christian nation," hearkening back to some mythical era when we functioned, nationally, in God's will. The dualism, meanwhile, permits the "I'm not voting for him to be my Sunday school teacher" line.

For In God We Trump's ex-vangelicals, transformationalism occasions Maloney's closing wish that as the political priorities of the Christian left gain traction, "we may, in this country of ours, eventually take care of each other in such a way that we resemble a just and Christian nation. We'll just have no need to call it that." And dualism appears, too, not least in the suggestion that abortion and same-sex relationships are inappropriate topics for politics, and evangelicals should keep publicly silent on these points lest they create "an American theocracy."

In God We Trump does well in probing the differences of values between white evangelicals and those who have left their ranks; more serious scrutiny is needed of how the basic framework for Christian engagement with politics has often stayed the same.

Beyond politics, however, the core of In God We Trump’s inquiry concerns what it means to be Christian. That question is resurrected weekly by each new scandal from the Trump administration, which maintains majority support from white evangelicals.

"Do you think [Trump's] a Christian?" Maloney asks The Washington Post's Elizabeth Bruenig, who rightly demurs. We cannot judge the destiny of another's soul, but what we can do is ask whether their behavior and character, as well our own, is Christlike. And on that point, In God We Trump amply makes its case: that however well-intentioned, white evangelicals' decision to get in bed with Donald Trump in utilitarian pursuit of political power is not something Jesus would do.

Bonnie Kristian was a deputy editor and acting editor-in-chief of TheWeek.com. She is a columnist at Christianity Today and author of Untrustworthy: The Knowledge Crisis Breaking Our Brains, Polluting Our Politics, and Corrupting Christian Community (forthcoming 2022) and A Flexible Faith: Rethinking What It Means to Follow Jesus Today (2018). Her writing has also appeared at Time Magazine, CNN, USA Today, Newsweek, the Los Angeles Times, and The American Conservative, among other outlets.

-

Minnesota's legal system buckles under Trump's ICE surge

Minnesota's legal system buckles under Trump's ICE surgeIN THE SPOTLIGHT Mass arrests and chaotic administration have pushed Twin Cities courts to the brink as lawyers and judges alike struggle to keep pace with ICE’s activity

-

Big-time money squabbles: the conflict over California’s proposed billionaire tax

Big-time money squabbles: the conflict over California’s proposed billionaire taxTalking Points Californians worth more than $1.1 billion would pay a one-time 5% tax

-

‘The West needs people’

‘The West needs people’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?Talking Point Peter Thiel and Larry Page preparing to change state residency

-

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one report

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one reportIN THE SPOTLIGHT By blocking an approved segment on a controversial prison holding US deportees in El Salvador, the editor-in-chief of CBS News has become the main story

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June

-

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardon

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardonTalking Point Convicted sex trafficker's testimony could shed new light on president's links to Jeffrey Epstein

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred