The mobile government loudspeaker in your pocket

Presidential text alerts are dangerously unnecessary

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Today at 2:18 p.m., my phone let out a banshee screech as it received the first ever Presidential Alert: "THIS IS A TEST of the National Wireless Emergency Alert System. No action is needed." On my iPhone, it looked and sounded like a flood or AMBER Alert, and joined a chorus of phones going off around me in the newsroom. It was the alarm heard 'round the nation. And it had been sent by the president himself.

Misinformation circulated in the days leading up to this test, initially delayed by Hurricane Florence, including rumors that President Trump will now be able to send all-caps tweets directly to your phone (he won't). The alert system will supposedly only be used in the case of a true national emergency. Nonetheless, the consequences of having such a system are insidious. The risks of the government being able to reach every smartphone-owning American in an instant greatly outweigh the benefits.

First, let's consider the unlikely situation in which the presidential alert would actually be used. The Federal Emergency Management Agency has gone to great lengths to assure that the system is exclusively for "true emergencies when we need to get the public's attention," as former Homeland Security chief Jeh Johnson put it to CBS This Morning. But in the past 60 years, no president has ever used the TV version of the national public warning system — not after the Cuban missile crisis, the John F. Kennedy assassination, the Oklahoma City bombing, or even on Sept. 11, 2001. Why? Perhaps because the media was perfectly capable of reporting information about these emergencies.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

The subtext here is that FEMA wants a system in place in the case of a cataclysmic disaster in which it couldn't communicate via traditional media (say, holding a press conference carried by every cable news network) or even directly via new social platforms (like, say, via President Trump's tweets). For instance, imagine a nationwide power grid attack, in which televisions or other forms of media and information might not be immediately accessible. In such a case, the president can now text everyone.

Or perhaps there are circumstances where time is of the essence — and literally every second matters. But even in the case of, say, an imminent coast-to-coast nuclear attack, a presidential alert delivered via text isn't going to realistically save your life. Instead, it will just push you to spend your last moments on Earth trying to stop your phone from screeching and then fretting over FEMA-babble.

The bewildering vagueness of these texts is a real problem. Remember, during a false alarm to phones in Hawaii earlier this year, a message said simply: "Ballistic missile threat inbound to Hawaii. Seek immediate shelter. This is not a drill." Part of the panic that followed, one resident told The New York Times, was that "there was no intel," no way of learning more immediately, with just a handful of minutes before hypothetical destruction.

There are far more problems with the system than just a lack of clarity, though. One is the potential constitutional violation of the "rights to be free from government-compelled listening," as stated in a lawsuit filed by plaintiffs in Manhattan. Although FEMA maintains that the alerts will only be used for mega-disasters, the infrastructure is now in place for it to, down the line, be used in other, more totalitarian ways. While presidents are currently restricted in what they can beam out to citizens by a 2015 law that specifies the alert system can't be used for anything that "does not relate to a natural disaster, act of terrorism, or other man-made disaster or threat to public safety," some critics find those terms frustratingly unspecific. After all, it was the alleged threat to national security that allowed President Trump to implement the so-called Muslim ban.

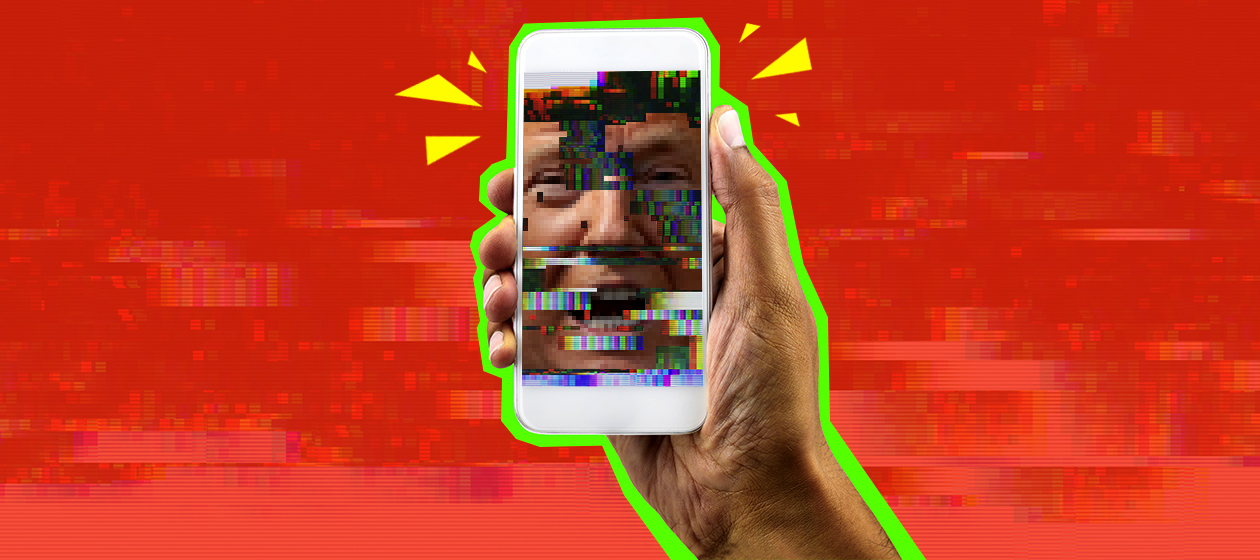

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Further, part of what makes the presidential alert more objectionable than old school or local alert systems is the intimacy of the government pinging a message straight to our phones — a private device that most people have on their bodies at all times, rather than something they choose to voluntarily tune in and out of. The authors of the aforementioned lawsuit claim that "subjecting plaintiffs to compulsory presidential alerts on their cellular devices turns those devices into government loudspeakers, against their wishes. Those loudspeakers operate on plaintiffs' persons wherever they are, turning the plaintiffs themselves into mobile government loudspeakers." That's a pretty spooky thought.

More problems could arise if the presidential alert system falls into, or is seized by, the wrong hands. Smaller-scale disasters have already taken place: Most notably the false alarm in Hawaii, which was caused by an employee hitting the "wrong button." Hackers will likely be tempted by the reward of reaching millions of phones under the guise of the president's office, too. No matter how much protection the government builds in, as Wired writes, "any system is hackable — and today that system sits on our bedside tables, is plugged into our ears, and is with us nearly all the time."

It's good to be prepared and informed, of course. But with the chances of a meteor strike or a nuclear attack so low, and with the alert offering little in the way of a public service by letting us know Armageddon is on the way, it falls on us to seriously interrogate how much we're willing to risk giving up in the name of hypothetical, instant, barebones information.

Jeva Lange was the executive editor at TheWeek.com. She formerly served as The Week's deputy editor and culture critic. She is also a contributor to Screen Slate, and her writing has appeared in The New York Daily News, The Awl, Vice, and Gothamist, among other publications. Jeva lives in New York City. Follow her on Twitter.