Elizabeth Warren is Democrats' best bet in 2020

She's the whole package

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Over the weekend, Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-Mass.) edged a little further toward the obvious, saying she would take a "good hard look" at running for the presidency, a quest for which she's been laying the groundwork for some time now. It behooves her party — and the country — to take a good hard look as well. Because there's a strong case to be made that Warren stands significantly above her competition in terms of her odds of winning the nomination, of winning the general election, and of being an effective president.

To make that case, let's first take a look at the competition.

Broadly speaking, the potential Democratic nominees fall into three categories. In one category are former Vice President Joe Biden and Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.). The advantages these two men have over the rest of the field are obvious: near-universal name recognition, a prodigious ability to raise money, and clarity about what they represent. But their problems are also obvious. They're both white men in their late 70s. They've both lost before (Biden twice). And they've each got personality similarities to Trump that make it difficult to draw a necessary contrast. Biden is a legendary gaffe machine with a reputation for being a little too hands-on. Sanders has a notorious temper and inability to work with others, and tends to scant the details of sweeping policy proposals.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Most important, they each represent only one half of the argument Democrats are having about how the party got here and where they should go. Biden would be running for an Obama restoration, Sanders for the "political revolution" that he started in 2016. It would be extremely difficult for either to capture the valid arguments — and the emotional appeal — of the other side.

In the second category are this year's equivalent of 1988's "seven dwarves" — a variety of politicians with some degree of promise and accomplishment who share broadly two things: They are largely unknown to the country at large, and they nonetheless think they could be president. Sens. Kamala Harris (Calif.), Cory Booker (N.J.), and Kirsten Gillibrand (N.Y.) are among this group, but the list can be extended almost indefinitely.

Why? Because none of these candidates have a compelling story to tell about why they are the ones to lead the fight against Trump. Rather, they are auditioning for the job by loudly proclaiming their agreement with whatever they believe their party's base wants to hear, even when it means running away from their own records (such as Harris' as a prosecutor, or Gillibrand's as a relatively conservative representative). That's a reliable recipe for weak leadership — and weak leaders tend to lose.

Finally, in the third category are the true outsiders. Celebrities like Oprah Winfrey and Dwayne Johnson, billionaires like Michael Bloomberg and Mark Zuckerberg, and tabloid phenomena like Michael Avenatti. Notwithstanding the legitimate accomplishments and appeal at least some of these individuals have, their mere presence on lists of possible contenders only makes the traditional nominees look weaker. But there's little to no evidence that the Democratic Party actually has any interest in nominating a Trump of their own.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Warren is the only contender who doesn't fit neatly into any of these categories. It's not just that her name recognition far outstrips that of the other politicians not named Sanders or Biden. She's also the only one running other than Biden or Sanders who could plausibly lead the Democratic Party base rather than catering to it. And she is a more plausible candidate than either of them to achieve party unity while also exciting Democratic passion.

More to the point, she's the only one not named Sanders or Biden who has a story to tell about why she should be the nominee that is compelling in terms of the forces that got us to where we are. That story, in a nutshell, is that American capitalism has been broken for a generation, and that it's going to take a change in how the government operates to fix it.

It's a populist message rather than a socialist one, and Warren takes pains to distinguish between the two every chance she gets. This might be because she wants to differentiate herself from Sanders, but it's also because it relates deeply to where she's coming from. Warren grew up in Oklahoma and was a Republican until the mid-1990s. She hasn't spent her whole life in politics, but was galvanized to enter the political arena because of the financial crisis, which revealed not only the fragility of our banking-driven economy, but the ways in which ordinary consumers were routinely taken advantage of by the same large financial institutions that drove the economy into a ditch.

Her answer was that free enterprise has to be fair to work and that regulation should be about protecting the little guy from abuse and preventing the big guys from getting so powerful that they can railroad anyone who stands in their way. Her orientation toward the financial crisis — which remains her political center of gravity — is more akin to that of a prairie populist like former Sen. Tom Harkin of Iowa than a Massachusetts mandarin like John Kerry.

She has some pretty big ideas. Taking on the cult of the CEO and the notion that shareholder value is all that corporations should care about is a pretty fundamental assault on how capitalism has worked in America. But it's not just sloganeering. Codetermination is a model of corporate governance that is entirely plausible, because it's the way things work in Germany. Warren is not just an advocate. It's thanks to her we had a Consumer Finance Protection Bureau in the first place. Very few of her primary opponents can make any comparable claim, and she wears fierce Republican opposition to her accomplishment as a badge of honor.

The point is not that she's the only potential candidate with a compelling biography or resumé or ideas. It's that her story about why she's in politics, and what the purpose of politics is, connects to the passions of the moment and is also fleshed out with specific but substantial ideas. It's the whole package — and it has the potential to get inside the argument that Trump himself has been making. That's what makes her potentially compelling as a general-election candidate and not just comfortable as a nominee.

None of that is to suggest that Warren will have an easy time in a general election against Trump. Trump will have all the benefits of incumbency, and if the world looks then like it does now, he'll have the additional benefits of a roaring economy and, if not peace, at least no additional wars started on his watch. And while I doubt most Americans will like Trump any more than they ever have, they will probably have gotten used to him to some degree.

But those will be challenges for any Democratic nominee. The Democrats will best meet that challenge by making their own argument about what the election is about, one that is responsive to the needs of the country, rather than letting their opponent — or their own base — do it for them. And they'll need a nominee who can embody that argument.

For what it's worth, Trump seems to be behaving like Warren is his likely opponent. He seems to relish the idea — and his advisers concur; the one they're worried about is Biden. But they should be careful what they wish for. Hillary Clinton's advisers were most worried about facing Marco Rubio, and relished the idea of facing the obvious loser Trump. And look how that turned out.

Noah Millman is a screenwriter and filmmaker, a political columnist and a critic. From 2012 through 2017 he was a senior editor and featured blogger at The American Conservative. His work has also appeared in The New York Times Book Review, Politico, USA Today, The New Republic, The Weekly Standard, Foreign Policy, Modern Age, First Things, and the Jewish Review of Books, among other publications. Noah lives in Brooklyn with his wife and son.

-

Health insurance: Premiums soar as ACA subsidies end

Health insurance: Premiums soar as ACA subsidies endFeature 1.4 million people have dropped coverage

-

Anthropic: AI triggers the ‘SaaSpocalypse’

Anthropic: AI triggers the ‘SaaSpocalypse’Feature A grim reaper for software services?

-

NIH director Bhattacharya tapped as acting CDC head

NIH director Bhattacharya tapped as acting CDC headSpeed Read Jay Bhattacharya, a critic of the CDC’s Covid-19 response, will now lead the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

-

‘The forces he united still shape the Democratic Party’

‘The forces he united still shape the Democratic Party’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

How are Democrats turning DOJ lemons into partisan lemonade?

How are Democrats turning DOJ lemons into partisan lemonade?TODAY’S BIG QUESTION As the Trump administration continues to try — and fail — at indicting its political enemies, Democratic lawmakers have begun seizing the moment for themselves

-

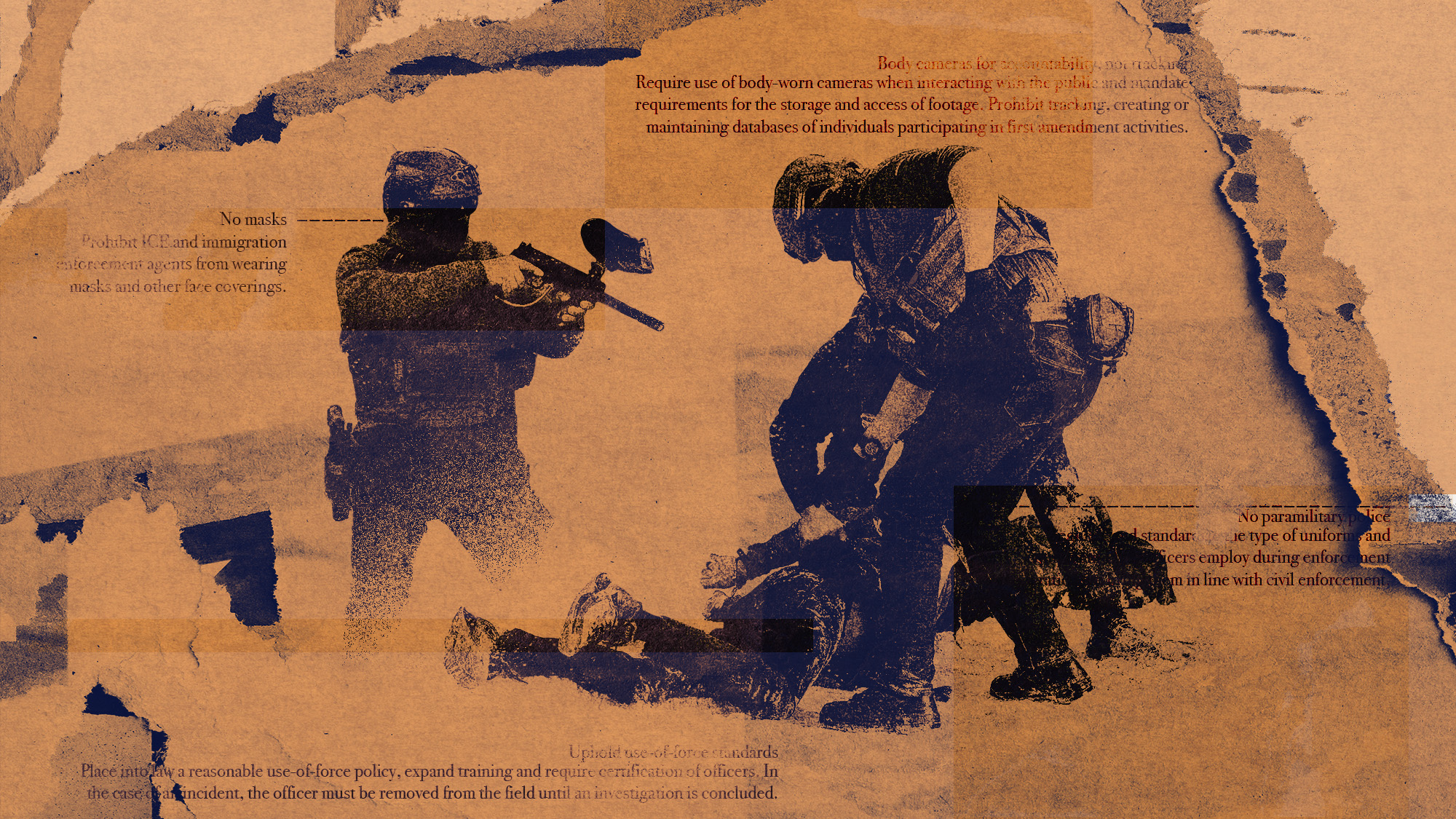

How are Democrats trying to reform ICE?

How are Democrats trying to reform ICE?Today’s Big Question Democratic leadership has put forth several demands for the agency

-

Democrats push for ICE accountability

Democrats push for ICE accountabilityFeature U.S. citizens shot and violently detained by immigration agents testify at Capitol Hill hearing

-

Democrats win House race, flip Texas Senate seat

Democrats win House race, flip Texas Senate seatSpeed Read Christian Menefee won the special election for an open House seat in the Houston area

-

Is Alex Pretti shooting a turning point for Trump?

Is Alex Pretti shooting a turning point for Trump?Today’s Big Question Death of nurse at the hands of Ice officers could be ‘crucial’ moment for America

-

‘Dark woke’: what it means and how it might help Democrats

‘Dark woke’: what it means and how it might help DemocratsThe Explainer Some Democrats are embracing crasser rhetoric, respectability be damned

-

How realistic is the Democratic plan to retake the Senate this year?

How realistic is the Democratic plan to retake the Senate this year?TODAY’S BIG QUESTION Schumer is growing bullish on his party’s odds in November — is it typical partisan optimism, or something more?