Buttigieg's bid to reboot Obamaism

Mayor Pete bets on hope and change

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The biggest surprise of the absurdly early contest for the 2020 Democratic presidential nomination is undeniably the meteoric rise of Pete Buttigieg, the 37-year old gay-married mayor of South Bend, Indiana, who officially announced his candidacy at an event on Sunday afternoon.

In a new Emerson poll released Monday morning, Buttigieg came in third with 9 percent. That's far behind the frontrunners Bernie Sanders and Joe Biden, with 29 and 24 percent respectively. But it beats a series of candidates with much greater name recognition, much longer track records, and much more prominent perches, including no fewer than five senators — Kamala Harris, Elizabeth Warren, Cory Booker, Amy Klobuchar, and Kirsten Gillibrand.

Buttigieg even edges Beto O'Rourke, the former House member from El Paso, Texas, who challenged and narrowly lost a Senate bid to Ted Cruz last November. When O'Rourke announced his own candidacy in mid-March, analysts predicted he might surge to the head of the pack on a wave of mainstream excitement and anticipation. Here, it seemed, was a possible successor to Barack Obama — a young, charismatic candidate who could catalyze a movement fueled by a feel-good desire for hope and change from the Trump era, just as Obama had done after eight years of George W. Bush. That impression was bolstered by the fact that several prominent members of the old Obama team swooned early on for Beto, making clear that they saw him as someone who could pick up the mantle from the 44th president, building and perhaps expanding on his enduring popularity.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Yet O'Rourke has hit the ground with a bit of a thud. Yes, he has enthusiasm and energy. But he isn't catching fire, at least not yet — and at least not in the way that Buttigieg appears to be doing.

Unlike Beto, no one was clamoring for "Mayor Pete" to jump into the race. He did it all on his own — creating a considerable splash at a CNN Town Hall in early March and then agreeing to a flood of interviews that kept his face, biography, accomplishments, and distinctive way of talking about politics close to the center of the action for the past month. The result is that he now leads the second tier of candidates — and could well surpass Beto in the contest to reboot Obamaism.

Journalists, activists, pundits, intellectuals — all of them, myself very much included, think that political campaigns should focus on policy. It's what those who care about ideas think is important. It's what establishes a candidate's seriousness, and what reveals his or her agenda — what the candidate wants to do with political power. That's why so many of us who lean left swoon for Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren, both of whom lead with very specific and ambitious policy proposals.

But Buttigieg understands what countless polls have verified, which is that most voters pay little attention to politics, and that even those who devote some time to it tend not to focus on policy specifics. Instead, these relatively low-information voters get carried along by a story — a story of a candidate and the story that candidate tells about America.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

That's where Buttigieg is excelling, just as Obama did before him.

What kind of stories do rank-and-file Democrats like to hear? Stories with a happy ending. And what's a happier ending than a candidate from a once-persecuted group triumphing over adversity to run for and possibly win the highest office in the land? That was Obama's story, and it's Buttigieg's, too, right down to the kiss he shared with his husband right after announcing his candidacy for the presidency.

This is the sunny side of the multicultural identity politics that defines the Democratic Party more thoroughly with each electoral cycle. The darker side of the same trend can be seen when each group attempts to elbow past the others, battling over who's the bigger victim of straight, white, male oppression, while failing to offer a compelling and hopeful vision of the country's future. The Obamaian approach has the distinctive political advantage of acknowledging obstacles to equality and justice while also demonstrating that progress continues — that underneath or alongside the ugliness of the Trump era, there can be hope for better days.

Paired with that love of overcoming adversity is the thrill of the party's standard-bearer positioning himself as Beyond Politics. Obama was a master of this, even when (especially in his first term) it left him ill-equipped to defend himself and his party against a Republican Party hellbent on absolute opposition. Buttigieg shows signs of mastering it, too, as when he speaks about Trump voters in terms of understanding and sympathy, suggesting it's "not accidental that some areas that have seen the most disruption in our social and economic life are those that are most likely to produce a lot of domestic extremists."

The Democratic love of presidential candidates who position themselves at least partially above the partisan fray is an expression of what the polls tell us. Whereas the Republican Party has a large base of ideological conservatives who consistently work to pull the GOP to the right, the Democratic base includes a great deal more self-described moderates. Those voters might not be centrists in ideological terms. But they long to be more than a faction. They want to speak for the country as a whole, to be unifiers. They resist the base-mobilization strategy that has been working for the Republicans. They don't just want to galvanize grassroots activists and win by manipulating America's counter-majoritarian institutions. The Democrats crave legitimacy. They want to be loved by as many people as possible, and they believe in their hearts that those supporters can and should include all people of good will.

What this boils down to is a question of style and, even more so, communication. The assumption is that the Democrats have a core set of moral and policy priorities that the party's nominee doesn't have to list and discuss in detail on the stump. Instead, he or she should stand for ideals, values, a vision. The Democratic nominee should be as broadly appealing as possible, an exemplar of the "better angels of our nature" as Americans. Feel good about him or her, and we'll feel good about ourselves — and vice versa.

In his recent hit job on Buttigieg from the left in Current Affairs, Nathan Robinson laceratingly parodies how this thinking sounds to someone devoted to pushing a more factional and policy-specific candidacy: "He's from the Rust Belt so he's authentic, but he went to Harvard so he's not a rube, but he's from a small city so he's relatable, but he's gay so he's got coastal appeal, but he's a veteran so his sexuality won't alienate rural people." Put in a less sneering tone, one might say that Buttigieg hopes to be many things to many kinds of people. Just as Obama was a professorial community organizer with a white Christian mother and a black Muslim father who lived abroad as a boy, admired the mainline Protestant Reinhold Niebuhr, and worshipped in a church run by a pastor who preached black liberation theology.

Like Walt Whitman — and like America itself — Obama contained multitudes. And so does the multilingual gay veteran from blue-collar Indiana.

Damon Linker is a senior correspondent at TheWeek.com. He is also a former contributing editor at The New Republic and the author of The Theocons and The Religious Test.

-

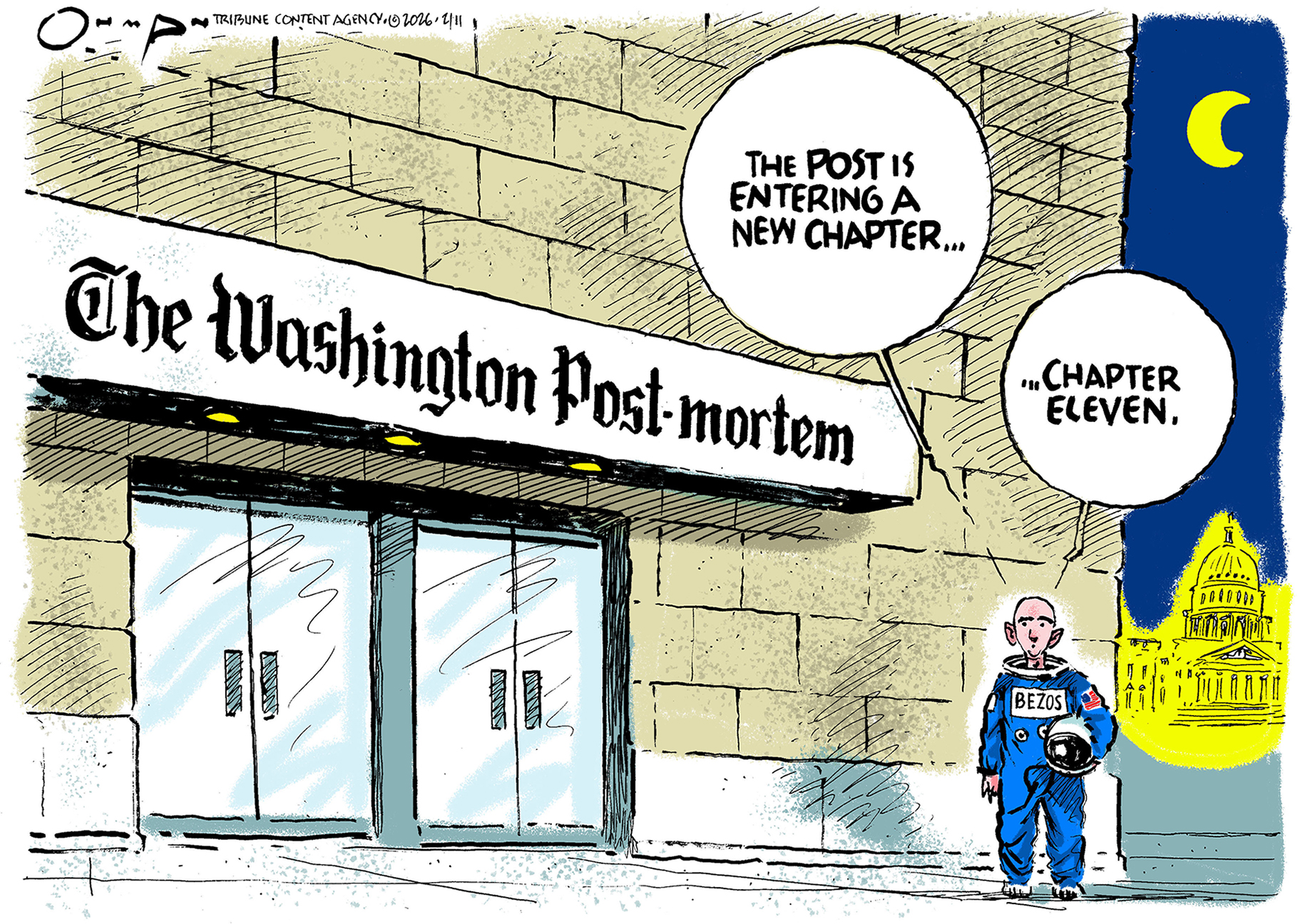

5 calamitous cartoons about the Washington Post layoffs

5 calamitous cartoons about the Washington Post layoffsCartoons Artists take on a new chapter in journalism, democracy in darkness, and more

-

Political cartoons for February 14

Political cartoons for February 14Cartoons Saturday's political cartoons include a Valentine's grift, Hillary on the hook, and more

-

Tourangelle-style pork with prunes recipe

Tourangelle-style pork with prunes recipeThe Week Recommends This traditional, rustic dish is a French classic

-

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?Talking Point Peter Thiel and Larry Page preparing to change state residency

-

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one report

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one reportIN THE SPOTLIGHT By blocking an approved segment on a controversial prison holding US deportees in El Salvador, the editor-in-chief of CBS News has become the main story

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June

-

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardon

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardonTalking Point Convicted sex trafficker's testimony could shed new light on president's links to Jeffrey Epstein

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

13 potential 2028 presidential candidates for both major parties

13 potential 2028 presidential candidates for both major partiesIn Depth A rare open primary for both parties has a large number of people considering a run for president

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration