Where are the real 2020 centrists?

Why Biden, Buttigieg, and Bloomberg don't really speak for "the center" of the Democratic Party or the broader American electorate

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The most persistent narrative of the 2020 race for the Democratic nomination is that it amounts to a battle between leftists (Bernie Sanders, Elizabeth Warren) and centrists (Joe Biden, Pete Buttigieg, and now Michael Bloomberg) over who is best suited to take on and take down President Trump.

But what if there are no true centrists in the 2020 race at all?

Oh sure, there are plenty of candidates who portray themselves as centrists — and other candidates, like Sanders and Warren, who delight in skewering these less left-leaning options for ideological heresy. But do the three Bs — Biden, Buttigieg, and Bloomberg — really speak for "the center" of the Democratic Party or the broader American electorate?

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

We have reason to doubt it. What they speak for is the center of public opinion in elite circles, where there is a broad consensus in favor of cultural liberalism and the primary point of disagreement is over economic policy. Should policymakers defer to markets, fiddle at the margins with tax rates, and work to soften the churning of capitalism but ultimately favor the encouragement of growth over fighting inequality? Or should they intervene more drastically in the economy by imposing sharply higher taxes, proposing sweeping regulations, and launching ambitious new social programs that might even include the nationalization of whole industries? That is the primary political dispute among Democratic elites, with the latter defining the left and the former supposedly defining the center.

This may have been how the center was understood in the country at large during the 1980s and '90s, in the immediate aftermath of the Reagan revolution. But that was also a time when Democrats were far more moderate on social issues than they are today. There were plenty of pro-life Democrats in the '80s, and Bill Clinton won two presidential elections while pledging to make abortion rare in addition to safe and legal. Both Clinton and Barack Obama (in the latter's first presidential campaign) opposed same-sex marriage. And until just a few years ago, most Democrats with national ambitions staked out positions on immigration far to the right of just about every candidate currently running for president.

To be a left-wing Democrat today is to combine maximally leftward positions on both social and economic policy, while to be a so-called centrist Democrat (at least in the eyes of the party's establishment, donor class, and activist base) is to combine precisely the same stances on social issues with somewhat less left-leaning positions on economic policy.

But why should that be considered the centrist option? What if the true electoral center of the country in our populist age is found somewhere else — in the ideological overlap between the economic left and social and cultural right?

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

As I argued in a series of columns last March, there is survey research to suggest that this is in fact the case. The Voter Study Group's June 2017 report on the 2016 election includes data showing that there are large numbers of voters who fall into an underserved ideological space that combines support for economically and socially populist views. These are people who would be powerfully drawn to a candidate who combined the economic message of Sanders or Warren with the sociocultural outlook of a Republican. (At times during his 2016 presidential campaign and in some of his speeches since, Trump has talked like a right-wing socialist who aims to transform the GOP into a "worker's party." But he has governed mostly like a plutocrat out to enrich himself and his wealthy friends.)

This doesn't mean that Democrats can or should stake out an absolutist opposition to abortion, same-sex marriage, and immigration. But it probably does mean that they would be well-advised to return to (and update) the general cultural outlook of the Clinton administration while combining it with a more left-wing economic agenda. In the present context, that would translate into a refusal to push the left's side of the culture war any further, and a willingness to pull back from some of the Democratic Party's more extreme stances on immigration in recent months and years.

Imagine a Sanders who defined himself as an economic nationalist promising to expand access to health care and college for American citizens instead of favoring the abolition of ICE and the decriminalization of border crossings. Imagine a Warren who spoke about her respect for religious freedom and the moral convictions of pro-life voters with half the passion that she reserves for the topic of economic injustice.

I'm hardly the only pundit to suggest that Democrats could scramble the Electoral College in all kinds of favorable ways by making an effort to place themselves smack dab in the middle of this alternative ideological center. Indeed, The New York Times's Ross Douthat recently went so far as to argue that Sanders is already close enough to staking out that territory that a social conservative like himself finds something reassuring about voting for him — on the grounds that Sanders is "the liberal most likely to spend all his time trying to tax the rich and leave cultural conservatives alone."

I wouldn't go that far myself. A Democrat wouldn't need, and shouldn't try, to mimic Trump's distinctive brand of xenophobic nastiness. But to reap electoral benefits, a Democratic nominee would need to show some sign of backing off from the most extreme ambitions of the cultural left. Other than displaying a good, old-fashioned socialist disinterest in non-material issues, Sanders has given no such sign, and neither has Warren. On the contrary, they've done everything possible at every point in the race to placate the very-online activists who play such an outsized role in Democratic politics these days.

And that is the main reason why such a shift toward the true American center is unlikely to happen anytime soon — because it would mean picking a fight with electorally marginal but interpersonally significant left-wing activists on Twitter and other social media platforms. Whether it's in the newsrooms of mainstream media outlets or in the campaign headquarters of first-tier presidential candidates, young staffers tend to take their cues from the online activists, and the people ostensibly in charge take their cues from the young staffers.

As long as that dynamic persists, so will the Democratic denial about the true center of American politics.

Damon Linker is a senior correspondent at TheWeek.com. He is also a former contributing editor at The New Republic and the author of The Theocons and The Religious Test.

-

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?Today’s Big Question Democrats want to rein in ICE’s immigration crackdown

-

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

Bad Bunny’s Super Bowl: A win for unity

Bad Bunny’s Super Bowl: A win for unityFeature The global superstar's halftime show was a celebration for everyone to enjoy

-

‘The forces he united still shape the Democratic Party’

‘The forces he united still shape the Democratic Party’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

How are Democrats turning DOJ lemons into partisan lemonade?

How are Democrats turning DOJ lemons into partisan lemonade?TODAY’S BIG QUESTION As the Trump administration continues to try — and fail — at indicting its political enemies, Democratic lawmakers have begun seizing the moment for themselves

-

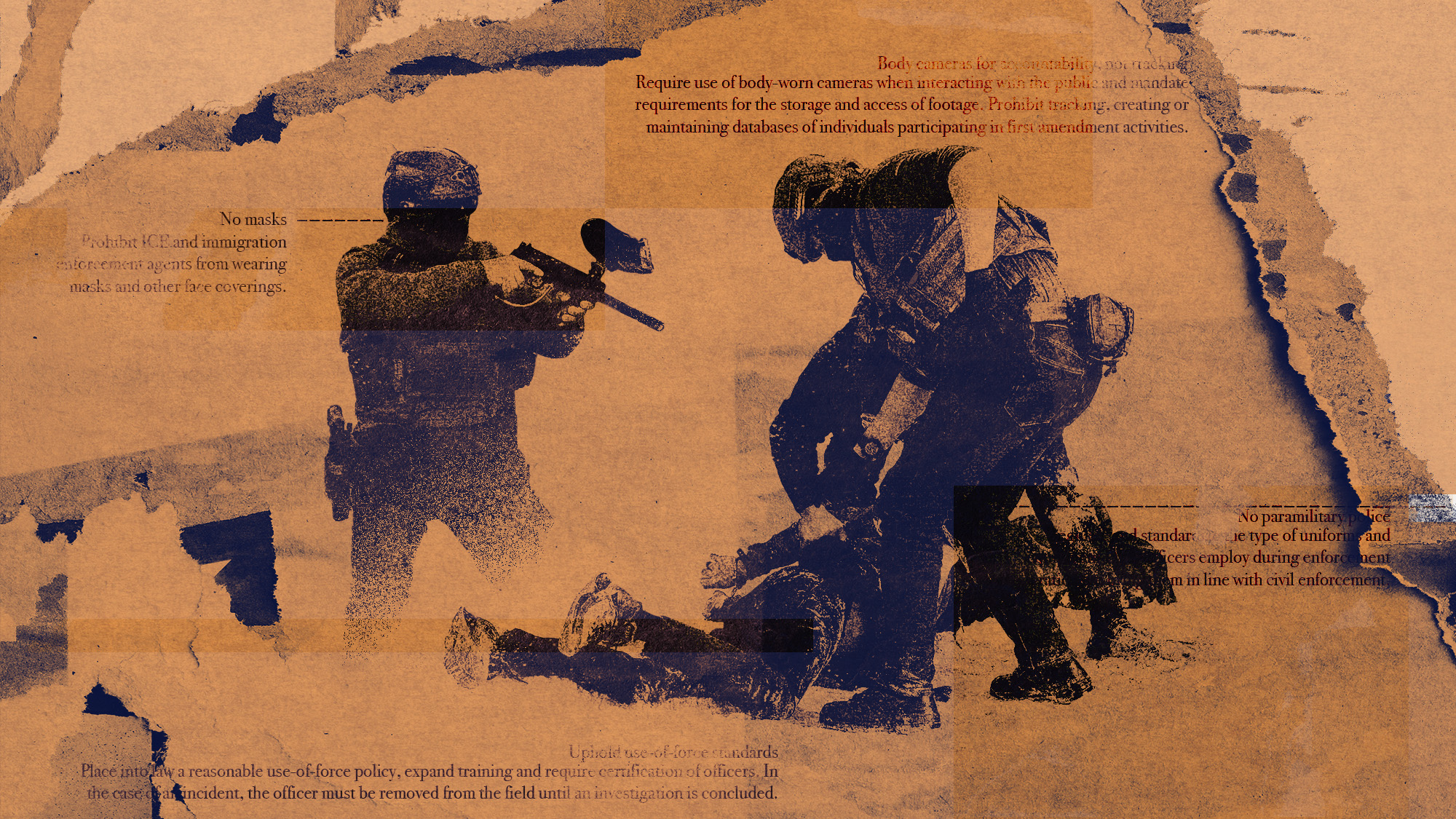

How are Democrats trying to reform ICE?

How are Democrats trying to reform ICE?Today’s Big Question Democratic leadership has put forth several demands for the agency

-

Democrats push for ICE accountability

Democrats push for ICE accountabilityFeature U.S. citizens shot and violently detained by immigration agents testify at Capitol Hill hearing

-

Democrats win House race, flip Texas Senate seat

Democrats win House race, flip Texas Senate seatSpeed Read Christian Menefee won the special election for an open House seat in the Houston area

-

Is Alex Pretti shooting a turning point for Trump?

Is Alex Pretti shooting a turning point for Trump?Today’s Big Question Death of nurse at the hands of Ice officers could be ‘crucial’ moment for America

-

‘Dark woke’: what it means and how it might help Democrats

‘Dark woke’: what it means and how it might help DemocratsThe Explainer Some Democrats are embracing crasser rhetoric, respectability be damned

-

How realistic is the Democratic plan to retake the Senate this year?

How realistic is the Democratic plan to retake the Senate this year?TODAY’S BIG QUESTION Schumer is growing bullish on his party’s odds in November — is it typical partisan optimism, or something more?