A manifesto for a new American center

The center isn't socially liberal and economically conservative. It's the opposite.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

These are ideologically disorienting times.

Partisan polarization is severe and increasing. Compromise has become a dirty word. Democrats fear Republicans have become fascists. Republicans accuse Democrats of embracing socialism. The center of the ideological spectrum, over which presidential candidates once fought to the electoral death, has become the political empty set, with leading members of both parties fleeing it at top speed and a self-proclaimed independent and centrist (potential) candidate for president, businessman Howard Schultz, pulling an anemic 4 percent in the polls.

But what if the problem is less that voters have abandoned the center and want politicians to embrace extremism than that their preferences no longer coincide with where the political lines have been drawn over the past several decades?

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

What if the center still holds, but just in a different place than we've come to expect it?

For the past 38 years, American politics has followed a script written by Ronald Reagan. Breaking sharply from the welfare-state liberalism of the Democratic Party that had set the agenda and tone for the previous 48 years, Reagan distinguished himself from the last two Republicans to hold the White House (Dwight Eisenhower and Richard Nixon) in staking out new ideological ground. Unlike his predecessors, Reagan would bring a libertarian, anti-government, pro-market sensibility to economic policy, working to cut taxes, expand regulatory reforms begun during the Jimmy Carter administration, and unleash private-sector economic growth.

On social issues and what came to be known as the culture war, the shift was in the opposite direction — away from the moral libertarianism bequeathed to the country by the counterculture of the 1960s and early 1970s. Reagan brought evangelical Protestants into the GOP and wooed Roman Catholics by promising to outlaw abortion, punish crime severely, and fight the moral degradation of the culture on multiple fronts.

Finally, on foreign policy, Reagan reignited the Cold War, picking it up where the Democrats had abandoned it with the Vietnam War and the party's shift to the left with George McGovern's nomination in 1972. Reaganite Republicans might be skeptical of government at home, but they had enormous faith in its power to effect change abroad in the form of military confrontation with adversaries.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

This mix of policies and ideas was so electorally potent that Democrats felt the need to assimilate to the new ideological dispensation. At first they resisted. It took losses in the presidential elections of 1984 and 1988 to convince the party that they had no choice but to adjust to Reaganite assumptions. The victorious presidential campaign of "New Democrat" Bill Clinton was an expression of his party's willingness to shift rightward in search of votes in the center of the spectrum.

Clinton believed strongly in free trade and relatively open immigration. He was tough on crime, left most of Reagan's tax cuts in place, favored welfare reform, promised to keep abortion legal and safe but also to make it rare, and was unafraid to use American military force abroad. And after the early debacle of health-care reform and the decisive repudiation of the 1994 midterm elections, he limited his ambitions in economic policy to small-ball fiddling at the margins of the Reagan revolution, famously encapsulated in the laundry lists of micro-policy proposals that clogged up the interminable State of the Union speeches of his second term.

From 1994 on, the political center would be defined as Reaganism lite: slightly less libertarian on economics, quite a bit more libertarian on social policy, and somewhat more inclined to seek international consensus before using the American military to police the liberal international order and punish those who dared to flout its norms and institutions.

Indeed, to this day this is what most of us mean when we talk about "the center" of American politics, whether it's the center-left, the center-right, or the independent center currently staked out by Schultz. It's pro-market, pro-free trade, pro-immigration. It favors keeping upper income taxes low (in comparison to their pre-Reagan baseline) and a tough approach to crime and welfare cheats. It's pro-choice (sometimes within limits) and liberal on other social issues. It's hawkish on foreign policy.

There's just one problem: There may not be very many voters in this so-called center.

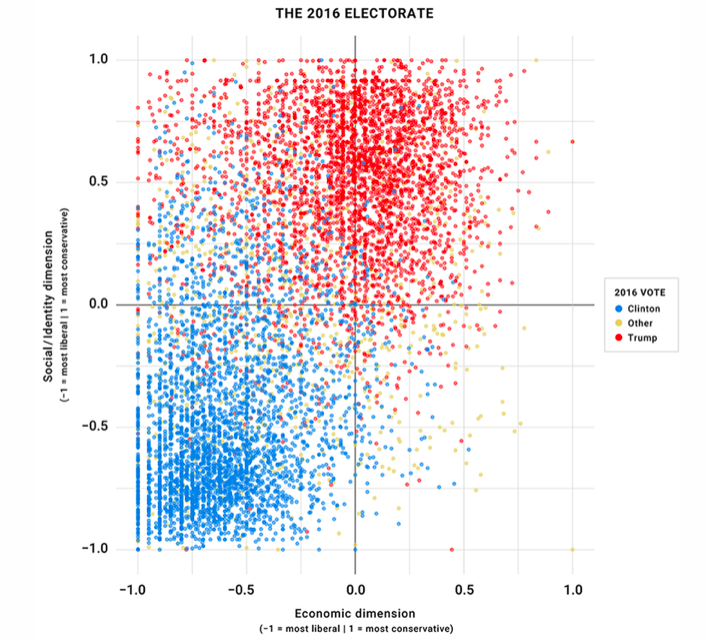

One of the most illuminating analyses of public opinion in the 2016 president election is the report of the Voter Study Group from June 2017. One chart in the report above all captures the paradox of the empty center better than anything else.

With each dot representing one of 8,000 voters in the 2016 presidential election, the vertical axis measures a voter's relative liberalism and conservatism on social issues and questions of national identity, with liberalism (or social libertarianism) higher on the lower half and conservatism higher on the upper half. The horizontal axis, meanwhile, measures relative liberalism and conservatism on economic issues, with those holding liberal positions further left and those who are more conservative (or economically libertarian) further right.

The chart clarifies several things about American politics. For one thing, Democrats are more thoroughly ideologically sorted, with the vast majority of them falling within the liberal-liberal quadrant on the lower left, than Republicans, who are consistently conservative on social issues and identity questions but fairly evenly distributed across the economic dimension from left to right.

And then there is what the chart tells us about the ideological center of American politics.

Politicians and pundits tend to define a centrist as someone who embraces relatively libertarian positions on both economics and social and identity issues. But note that these positions come together in the lower right quadrant of the chart — and that this quadrant has by far the fewest voters. The center, as typically defined, really is the empty set.

But there is another center in American politics — one that is the diametric opposite, in ideological terms, of the libertarian one on which we tend to fixate. This other center is filled with large numbers of voters who most likely feel under-represented by the two parties. Instead of combining a Republican position on economic issues with a Democratic position on social and identity issues, this other center does the reverse, combining a Republican position on social and identity issues with a Democratic one on economics.

That's the upper left quadrant on the Voter Study Group chart, and it's where Donald Trump appeared to be situating himself when he skewered various Republican pieties during the GOP primaries of 2016. Like any Republican of the past three decades, he professed to be pro-life and promised to appoint conservative justices to the Supreme Court. He boosted himself further than most Republicans on the social-identity axis by staking out a harshly draconian position on immigration. But he combined these views with promises to preserve and strengthen Social Security, Medicare, and other government entitlement programs. He also spoke of the need to make health care more affordable and accessible to all. And he expressed a willingness to impose restrictions on trade to bolster sagging segments of the American economy.

Put it all together and we're left with a Trump campaign firmly situated in the upper-left quadrant of the chart — somewhere in the vicinity of a new, post-Reagan center. Which perhaps helps to explain why 2016 voters tended to view Trump as a moderate.

They don't view him that way anymore, no doubt in large part because his rhetoric and actions on immigration and other issues have been so harshly polarizing. But it's probably also because for most of the past two years Trump has governed as far more of a traditional Reaganite Republican (situated in the upper right quadrant) than one might have guessed he would from his campaign. Paul Ryan set the policy agenda, with the signature achievement of the first two years of Trump's presidency a massive tax cut for corporations.

But that doesn't mean the upper-left quadrant should be ignored. On the contrary, it may well be the new electoral sweet spot — the half-hidden gravity well of American politics in the early 21st century that warps the political fabric of the country's political culture and disrupts the plans of politicians, strategists, and parties. Whether the GOP taps into this new center by convincingly purging itself of plutocratic prejudices and remaking itself into a genuine "worker's party," or the Democrats appeal to it by combining their economic progressivism with a form of inclusive civic nationalism, tens of millions of voters await someone to respond to their distinctive mix of anxieties and concerns.

The first step toward crafting such a response involves an effort to think through what such an authentically centrist agenda might look and sound like.

This is the first article in a four-part series on the new political center. Part two can be found here.

Damon Linker is a senior correspondent at TheWeek.com. He is also a former contributing editor at The New Republic and the author of The Theocons and The Religious Test.

-

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?Today’s Big Question Democrats want to rein in ICE’s immigration crackdown

-

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

Bad Bunny’s Super Bowl: A win for unity

Bad Bunny’s Super Bowl: A win for unityFeature The global superstar's halftime show was a celebration for everyone to enjoy

-

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?Talking Point Peter Thiel and Larry Page preparing to change state residency

-

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one report

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one reportIN THE SPOTLIGHT By blocking an approved segment on a controversial prison holding US deportees in El Salvador, the editor-in-chief of CBS News has become the main story

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June

-

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardon

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardonTalking Point Convicted sex trafficker's testimony could shed new light on president's links to Jeffrey Epstein

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred