Democrats are sleepwalking into a Biden disaster

It's time for his rivals to go on the attack

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The Democratic primary has had much hue and cry over Pete Buttigieg, Elizabeth Warren, and Bernie Sanders of late. Yet the front-runner continues to be former Vice President Joe Biden, and there is little sign as yet that he is going to lose his lead, despite his fumbling campaign.

The Democrats are sleepwalking into a disaster.

Biden has so far run a lackluster at best campaign. He is doing relatively few events, and often puts his foot (or his wife's fingers) in his mouth at the ones he does. At debates and campaign events he routinely flubs details of current events or even his own campaign machinery. His own campaign reportedly cut back on campaigning earlier in the year for fear of negative press, and his allies have suggested he do the same.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Biden can't even raise much money, despite his deep-pocketed connections from a career as a handmaiden for the corporations that use Delaware as a flag of legal convenience. As of mid-October, he had less than a third as much cash on hand as Bernie Sanders — which probably prompted Biden to abandon his pledge to not accept support from corporate-backed outside super PAC groups, drastically undermining a decade of organizing effort to get Democrats to stop taking corporate money at a stroke. Even the pipsqueak Buttigieg has raised vastly more money, perhaps because even some big establishment donors are reportedly alarmed by Biden's weak campaign.

Biden has no explanation for why he is suitable to lead a party whose base is rapidly moving leftward, given his history on the center-right of the party. Why should a guy who voted for the Iraq War, financial deregulation, and bankruptcy reform; who was a key architect of rolling back school integration; and who is implicated in dozens of other historic atrocities be appropriate for the Democratic Party of 2019? He has not even addressed the question — on the contrary, he continues to promise an utterly impossible return to bipartisan compromise, and to boast about his friendship with segregationist Dixiecrats.

On the specific politics of 2020, Biden has not even bothered to come up with a persuasive answer to his son Hunter's involvement with the Ukrainian energy company Burisma, which has dominated media coverage for months by way of the Trump impeachment inquiry. As New York's Eric Levitz argues, Hunter collecting $50,000 a month to sit on a board for which he had no qualifications was clearly corrupt influence peddling. Biden could still argue somewhat convincingly that he did nothing to help his son, and perhaps make an emotional case that, while he knew what Hunter did was wrong, he was so devastated by the death of his other son Beau that he couldn't bring himself to rein him in. That might even be true! But at a minimum, a presidential front-runner should have a clear response to such a critical problem.

Instead, Biden gets mad when the subject is brought up. The best he could muster to Mike Allen at Axios was "I don't know what he was doing ... I trust my son." When a voter at one of his campaign events brought up the subject, Biden called him a "damn liar" and challenged him to a push-up contest. Not exactly sharp political messaging.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

If Biden is nominated in 2020, Trump is going to repeat the formula that made Hillary Clinton's emails the dominant story of 2016. He'll say "BIDEN UKRAINE CORRUPT" 90 billion times, and the New York Times political reporters with Both Sides brain poisoning will helplessly validate the narrative. The rest of the press will follow their lead. Biden will take on the vague appearance of being The Corrupt One despite Trump being monumentally worse in every possible respect. Even observers who share Biden's basic political outlook are extremely worried about this possibility.

Some of Biden's support seems to come from the perception that, like Trump, he is somehow immune from the normal laws of politics. Several scandals and gaffes that would have ended a typical campaign dented his support not at all — which is to say his backers are creating a self-fulfilling prophesy that if they support him no matter what he does then he will continue to be supported.

In reality, nominating Trump in 2016 was a terrific gamble by the Republican Party. His base of riled-up kooks sticks with him through thick and thin, but his constant scandals and unhinged tweeting really did sap his support among the broader population — making him the most unpopular nominee in the history of polling. Even today, presiding over the strongest economy in two decades, he remains markedly unpopular. Trump just had the extraordinary good luck to draw a hapless, incompetent opponent who was nearly as unpopular as he was. Any other serious candidate, from Bernie Sanders to Barack Obama, almost certainly would have bested Trump handily.

So far Biden has not drawn many attacks from the other candidates. They seem to accept the widely-held belief that his campaign will surely collapse from the inside at some point. But if that were true then it surely would have happened by now. If any Democrats want to halt the potential disaster of a Biden nomination, they're going to have to do something about it.

Want more essential commentary and analysis like this delivered straight to your inbox? Sign up for The Week's "Today's best articles" newsletter here.

Ryan Cooper is a national correspondent at TheWeek.com. His work has appeared in the Washington Monthly, The New Republic, and the Washington Post.

-

Local elections 2026: where are they and who is expected to win?

Local elections 2026: where are they and who is expected to win?The Explainer Labour is braced for heavy losses and U-turn on postponing some council elections hasn’t helped the party’s prospects

-

6 of the world’s most accessible destinations

6 of the world’s most accessible destinationsThe Week Recommends Experience all of Berlin, Singapore and Sydney

-

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule works

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule worksIn the Spotlight The law is at the heart of the Colbert-CBS conflict

-

‘The forces he united still shape the Democratic Party’

‘The forces he united still shape the Democratic Party’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

How are Democrats turning DOJ lemons into partisan lemonade?

How are Democrats turning DOJ lemons into partisan lemonade?TODAY’S BIG QUESTION As the Trump administration continues to try — and fail — at indicting its political enemies, Democratic lawmakers have begun seizing the moment for themselves

-

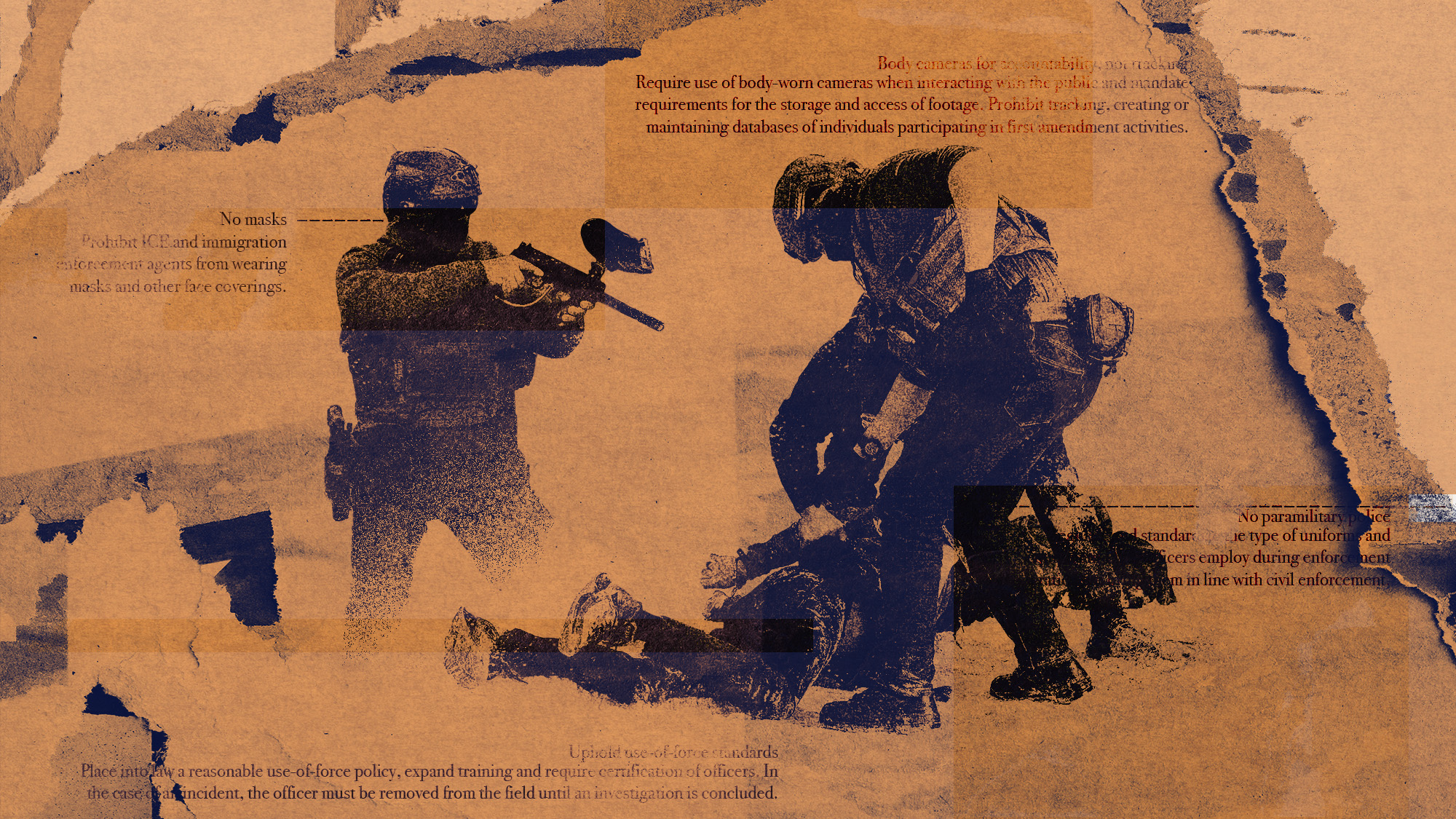

How are Democrats trying to reform ICE?

How are Democrats trying to reform ICE?Today’s Big Question Democratic leadership has put forth several demands for the agency

-

Democrats push for ICE accountability

Democrats push for ICE accountabilityFeature U.S. citizens shot and violently detained by immigration agents testify at Capitol Hill hearing

-

Democrats win House race, flip Texas Senate seat

Democrats win House race, flip Texas Senate seatSpeed Read Christian Menefee won the special election for an open House seat in the Houston area

-

The ‘mad king’: has Trump finally lost it?

The ‘mad king’: has Trump finally lost it?Talking Point Rambling speeches, wind turbine obsession, and an ‘unhinged’ letter to Norway’s prime minister have caused concern whether the rest of his term is ‘sustainable’

-

Is Alex Pretti shooting a turning point for Trump?

Is Alex Pretti shooting a turning point for Trump?Today’s Big Question Death of nurse at the hands of Ice officers could be ‘crucial’ moment for America

-

‘Dark woke’: what it means and how it might help Democrats

‘Dark woke’: what it means and how it might help DemocratsThe Explainer Some Democrats are embracing crasser rhetoric, respectability be damned