Why the good economy is bad for Boeing

The company is shutting down production of the 737 Max at an inopportune time

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

There's never really a good time for the biggest manufacturer in America to halt production of its biggest-selling aircraft. But Boeing, which announced on Monday it's temporarily halting production on the 737 Max, has chosen a particular inopportune time.

For workers and the U.S. economy, the blow will be softened by the fact that we're in an uncommon boom time. But for that exact same reason, the consequences of the shutdown for Boeing itself could be even worse. If you're a big manufacturer who has to put the brakes on a major business line, then — from the standpoint of crass corporate self-interest — you actually want to do it when the economy is in the doldrums.

Eventually Boeing will want to spin production of the 737 Max back up. And America's ultra-low unemployment rate will make that harder.

Article continues belowThe Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

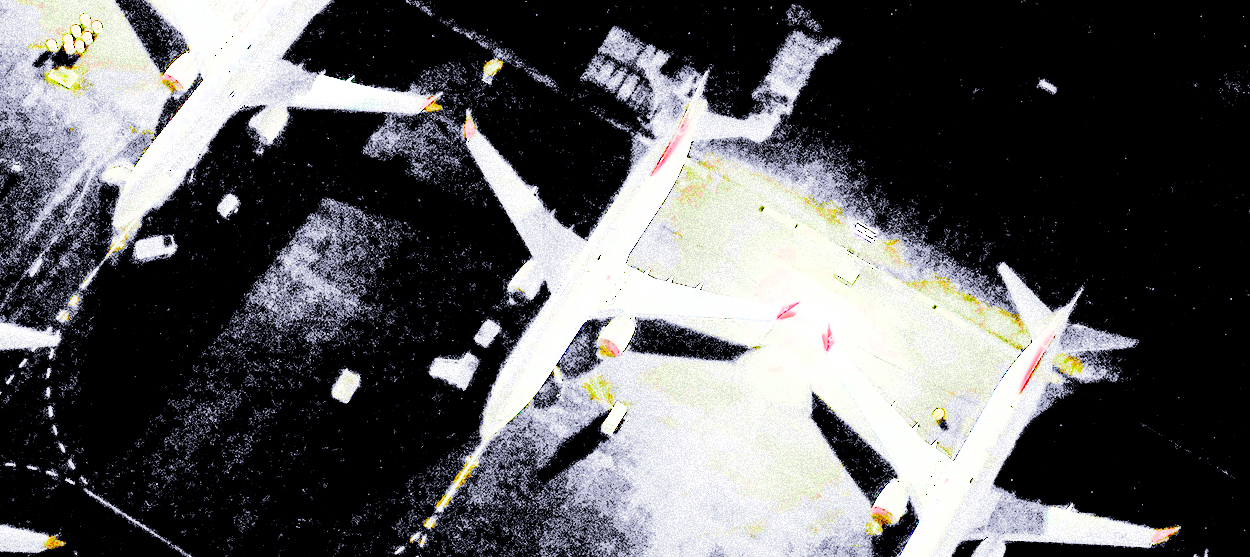

The 737 Max was originally grounded by government regulators back in March, after two crashes killed 346, revealing potentially significant problems with the plane — particularly with its flight software. Boeing repeatedly said it anticipated the 737 Max would be back in the air by the end of 2019, and its Renton, Washington factory kept cranking the planes out accordingly, only slightly cutting monthly production of new planes from 52 to 42. But so far, Boeing's fixes have left both American and European regulators cold, and the crisis has gone on to become the biggest screw-up in the company's century-long history. This week, Boeing finally knuckled under to reality and announced it was stopping further production of the planes.

Boeing's been bleeding cash, both to keep producing the 737 Max, and to reimburse all the buyers who purchased the planes but can't fly them. Stopping production will allow Boeing to staunch the losses and keep its finances in better balance. But as I said, at some point Boeing will want to start production back up again. That will require restarting a vast infrastructure of suppliers, workers, and factories. And the crucial bit is, for that infrastructure to be spun back up once the 737 Max crisis is over, that infrastructure will also have to remain in place — effectively in a state of suspended economic animation — during the shutdown. To get even more concrete: all the workers involved in the process will have to remain available.

This brings us to the happy state of the U.S. economy. Granted, the current boom is often overblown: Despite a remarkably low headline unemployment rate, wage growth is still a bit sluggish, and other indicators of labor market slack — particularly prime-age employment — remain rather high. But there's no doubt the economy is doing much better right now than it has in a good long while. And one of the best things about a hot economy is it brings more employment opportunities for workers: If they get laid off from one job, or a particular gig just isn't working out, their chances of finding good employment elsewhere are much higher.

That's good for workers, but it's a problem for a manufacturer who wants to temporarily halt a particular line of production. The manufacturer wants to hold on to the network of workers and activity that supply that production, but the workers themselves have both the motive and the means to jump ship.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Boeing of course knows this. The company immediately said it would not lay off or furlough any of the 12,000 employees who actually assemble the 737 Max at its Renton factory, but will instead reshuffle them onto other projects. This can be spun as corporate selflessness: Boeing making sure people keep their jobs, even at a cost to its bottom line. But there's also a big element of strategic self-interest involved: When the 737 Max kicks back into gear again, all those workers will be right there, still on Boeing’s payroll, ready to be put back to work doing what they already know how to do.

The thing is, while what happens at Boeing's own factory is a business decision the company can control, what happens at Boeing's suppliers is another matter entirely.

General Electric, for example, builds the 737 Max's engines. Spirit AeroSystems in Wichita, Kansas builds the plane's fuselages. Hundreds of other suppliers and smaller firms who contribute various bits to the plane's final construction are scattered throughout the United States. Now that Boeing is halting production, each one of those companies is going to have to decide what to do: Will it lay off workers? Furlough them? Move onto other buyers? Each one of those decisions will have consequences for how easy (or hard) it will be for Boeing to get that vast network of supply chains back up and running whenever 737 Max production finally recommences. More specifically, in a hot economy, all those suppliers will have a harder time holding onto their own workers if they decide to wait the halt out rather than just move on.

"Many suppliers had said they favored Boeing maintaining some production, citing the risk of losing workers in a tight labor market during a halt," the Wall Street Journal reported. "They said furloughing staff and stopping machinery would be harder than lowering production, and that restarting assembly lines would be costly."

Again, Boeing knows this. The company will try to extend suppliers as much cushion as it can, by doing things like keeping contracts alive and continuing to buy some parts. But obviously Boeing can only eat those costs for so long, and then its suppliers can only wait for so long. General Electric, for instance, already said it expects its own cash flow to drop as much as $1.4 billion this year due to the slowdown. Everything really depends on how long the shutdown lasts, and even now no one really knows.

There's another lesson in this too. Thanks to laziness and corner-cutting, Boeing committed a massive error that got hundreds of people killed. It may well survive the blunder, but in a booming economy, it's not just other companies that put competitive pressure on a business when it screws up — it's the workers as well, who can jump ship for other employers. When the economy is in the doldrums — a depressingly common state, in recent decades — laziness and corner-cutting are easier to get away with.

When the labor market's hot, it's at least somewhat more likely that capitalist competition will actually do what it's supposed to do and punish corporate misbehavior.

Jeff Spross was the economics and business correspondent at TheWeek.com. He was previously a reporter at ThinkProgress.