Why the early primaries are especially important for Bernie Sanders

Most electability arguments can't really be tested. But we'll know pretty quickly if the 'political revolution' is working.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The 2020 Democratic primary campaign has been a contest not merely of which candidate's ideas and policies most appeal to Democratic voters but of which potential nominee is most likely to defeat Donald Trump in November's general election. Polling has shown that a majority of democratic voters say it is more important for the nominee to have the best chance of beating Trump than to share their position on most issues, and several of the Democratic contenders have made "electability" central part of their campaign message. The problem with electability arguments, however, is that most of the time they can't actually be put to the test until it's too late.

Usually, electability claims are based on pretty limited data or vague theories. Candidates can point to their past election performance in swingish states, like Sen. Amy Klobuchar does in Minnesota, arguing the ability to perform well in a purple-ish, upper Midwest state would have made the difference for Democrats in the 2016 election. But how you reach voters in a state with just five million residents doesn't necessarily translate to running in a diverse country with 330 million people. Those candidates may perform better in their home states but they may also perform much worse in others.

Former Vice President Joe Biden can point to hypothetical general election polling, where he has consistently performed the best of all the Democratic candidates against Trump, but polling a year out has limited value. Indications are that Biden is benefiting from high name recognition, which anyone who is the nominee would eventually match. Sen. Elizabeth Warren supporters, meanwhile, can argue she would bridge the progressive and centrist wings of the party. Yet indications are that disdain for Trump would go a long way toward unifying Democrats behind any nominee.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

The one exception to these cases, though, might be Sen. Bernie Sanders, whose electability argument is fundamentally different from the others.

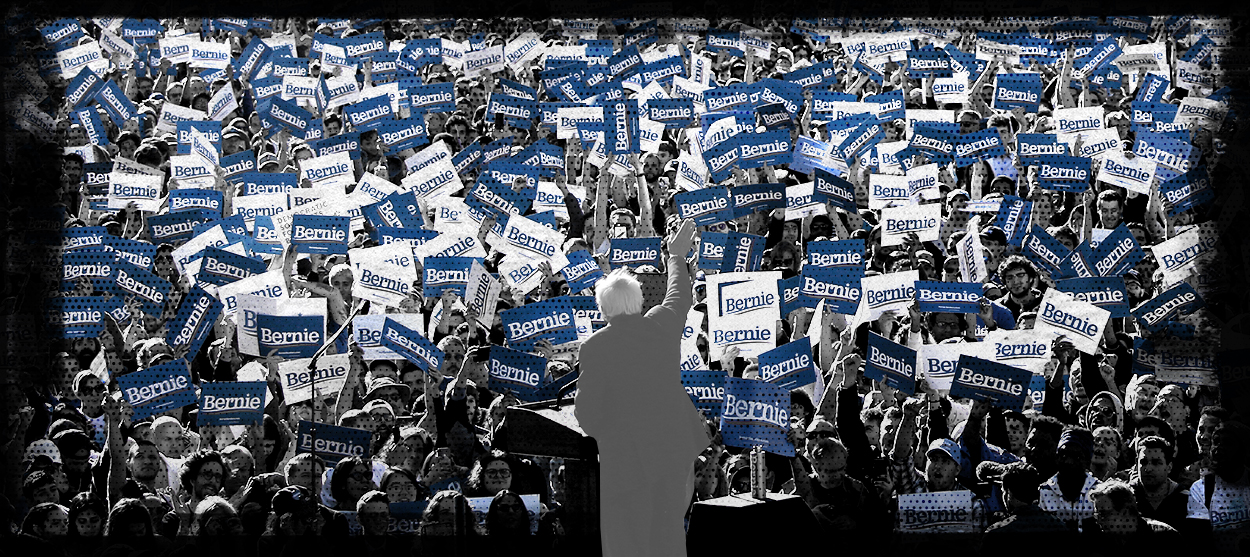

The Sanders campaign believes he can bring new people into the electoral process — enough to more than make up for any shortfalls he might have among older voters or some more traditional swing voters compared to Biden. That is what his "political revolution" is about. The whole campaign is based around bringing in non-voters, picking up former third-party voters, activating infrequent voters, and getting regular voters more engaged in organizing. The Sanders campaign is investing heavily in relational organizing, getting people to contact their friends and family and to knock on the doors of their neighbors. He is not trying to win the current electorate so much as create a new, much more favorable one.

Many past candidates have claimed they would reshape the electorate, and many have failed, but if the Sanders campaign can, it should be evident as soon as states start voting in the primary. Polling in the early states of Iowa, New Hampshire, and Nevada all show very close races with Sanders at or near the top. If Sanders is really activating non-voters in a way that can make a difference in the general election against Trump, we should clearly see that in the results of these contests. In the 2016 Democratic primary, only about 30 million people voted compared to the over 136 million who voted in the general election, so it is in theory much easier to swing a primary via greater turnout. If Sanders is uniquely able to excite new and infrequent voters, we should see historically high turnouts and surprisingly strong performances from Sanders in these early states. He should not only gain the momentum of the victories but also benefit from a real demonstration of his electability case.

If turnout isn't much different from 2016, however, even if Sanders narrowly wins, his electability argument is basically dead. If he can't get tens of thousands more to turn out in the early primaries, there is little reason to believe he would uniquely be able to get millions more to turn out in November.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

That doesn't necessarily mean he will lose the primary or the general election. Sanders has a solid base of support, and with a large, divided field he could win the nomination with a plurality of Democratic support. Similarly, President Trump is deeply unpopular, and the race is likely to be a referendum on his leadership. There is a legitimate argument that any Democratic nominee could beat him in November by simply being the alternative. But if Sanders can't drive turnout in the early primaries, it is unlikely he will be reshaping our politics. Instead, he will be trying to get lucky in a divided field and hope to ride an anti-Trump wave.

Want more essential commentary and analysis like this delivered straight to your inbox? Sign up for The Week's "Today's best articles" newsletter here.

Jon Walker is the author of After Legalization: Understanding the Future of Marijuana Policy. He is a freelance reporter and policy analyst that focuses on health care, drug policy, and politics.

-

Political cartoons for February 7

Political cartoons for February 7Cartoons Saturday’s political cartoons include an earthquake warning, Washington Post Mortem, and more

-

5 cinematic cartoons about Bezos betting big on 'Melania'

5 cinematic cartoons about Bezos betting big on 'Melania'Cartoons Artists take on a girlboss, a fetching newspaper, and more

-

The fall of the generals: China’s military purge

The fall of the generals: China’s military purgeIn the Spotlight Xi Jinping’s extraordinary removal of senior general proves that no-one is safe from anti-corruption drive that has investigated millions

-

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?Talking Point Peter Thiel and Larry Page preparing to change state residency

-

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one report

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one reportIN THE SPOTLIGHT By blocking an approved segment on a controversial prison holding US deportees in El Salvador, the editor-in-chief of CBS News has become the main story

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June

-

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardon

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardonTalking Point Convicted sex trafficker's testimony could shed new light on president's links to Jeffrey Epstein

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred