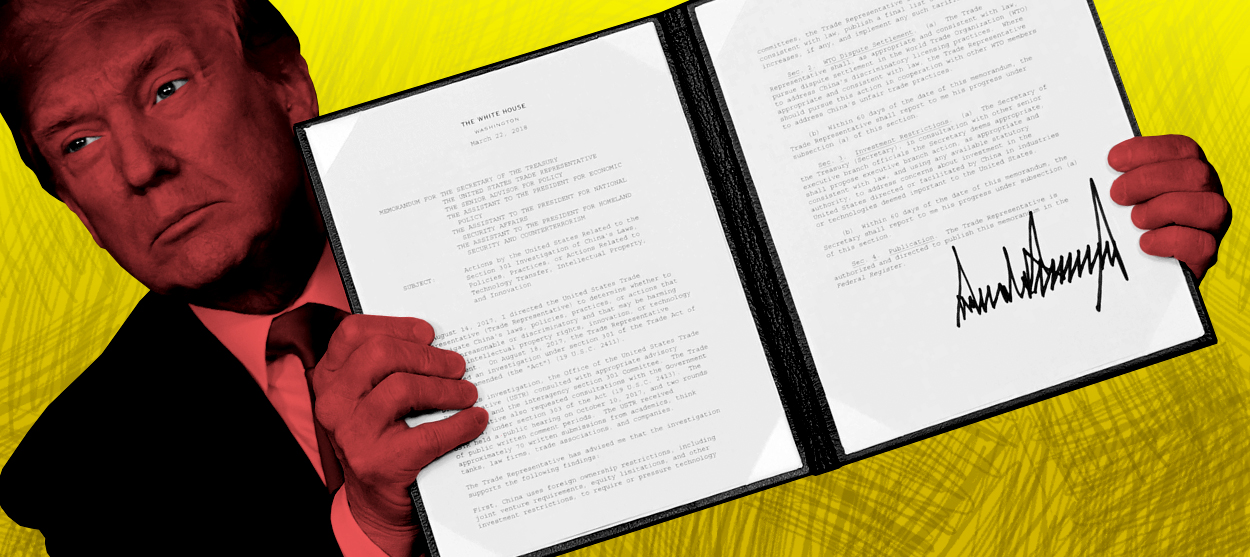

Did the U.S. win the trade war? Depends what we were fighting for.

How to understand Trump's "phase one" deal with China

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The United and China have finally called a truce in their trade war. What the Trump administration is calling "phase one" of a hoped-for larger agreement reduces tariffs on Chinese exports in exchange for China's commitment to addressing intellectual property theft and to purchasing $200 billion in additional American goods and services.

Is that what victory looks like? It depends very much on what objective you think the war was being fought for in the first place.

Going all the way back to his primary campaign, there have been two ways to understand Trump's rhetoric towards China. From the perspective with the greatest continuity with prior American policy, Trump was proposing a more aggressive approach to traditional ends. Getting tough would force China to change its fundamental approach to trade and its model of economic development. China would have to agree to respect American intellectual property, open protected sectors like finance to greater competition, stop forcing American companies to transfer technology to Chinese partners as a condition of doing business in China, and scale back or eliminate its extensive subsidies for favored industries such as steel, solar energy, and advanced computing and communications technology.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Viewed in the context of those objectives, Trump's trade deal does make some real progress. China has made commitments on intellectual property and technology transfer, has removed some regulatory barriers to imports of American agricultural products, and may need to allow more competition in finance to meet its aggregate commitments to purchase American services. But many of these commitments are ones the Chinese have made before, and tariffs are being reduced even though the major structural issues that prompted the trade war in the first place have been left largely unaddressed. Moreover, enforcement of the new trade deal will be no easier than past promises. In fact, since there is no independent authority established to enforce the deal, the true enforcement mechanism is ultimately the threat to restore the high tariffs, which would take both parties back to the status-quo ante.

The gains, then, are real but small, and it's debatable whether the economic cost, particularly to American farmers, was worth what has been won. More to the point, though, if these were the objectives, critics should be asking why the Trump administration pulled out of the Trans-Pacific Partnership in the first place and shifted to a strategy of bilateral confrontation. That deal would have provided many of the sought-after protections for American intellectual property and mechanisms for preventing other countries from using non-tariff regulatory barriers and subsidies to keep out American products and services. It wouldn't have included China, and therefore wouldn't have precluded a get-tough approach to trade with China. But the objective of the TPP was to create an architecture that China would ultimately want to join for the sake of its own competitiveness, and the multilateral structure would arguably have provided greater leverage to push Chinese liberalization.

There was another way to view Trump's objectives, though, one that became more and more plausible as the sheer scope of his trade war expanded. From this perspective, the objective was less to change China than to decouple from it, unwinding the great integration that took place since China joined the World Trade Organization. The opening to China had allowed American companies to rely on Chinese components for their supply chain, devastating American manufacturing; perhaps we had to close that door to reopen shuttered American plants. And if there was a cost to American consumers, perhaps it was worth paying in order to restrain the rise of China as a peer economic and geopolitical competitor.

From that perspective, the truce looks very much like a retreat, albeit a small one. One can debate who gains the most in the short term from a truce — both America and China have been suffering, and both will get some relief — and whether it sticks or not is still unknown. Sticking, though, would mean that integration will resume, on terms somewhat more favorable to American corporations and farmers, with little obvious benefit for American workers or the industries devastated by the China shock. The best that can be said from this perspective is that no concessions have been made on America's sovereignty, but this is precisely what limits the benefit of the deal in terms of business investment; investors are unlikely to want to put too much at risk when the trade war could be restarted at any time.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

But the trade war was never a very plausible way on its own to restore America's manufacturing sector, nor to move supply chains back on shore. While both America and China paid the cost of the tariff war, the main beneficiaries were third countries in Southeast Asia and Latin America, the former replacing China in global supply chains and the latter replacing America as a supplier of agricultural products to China. As Chinese investment has increased in all these regions, the trade war did not even obviously reduce the scope of Chinese influence. If Trump actually believed that neo-mercantilist strategies were the way to make America great again, he needed to find ways to direct investment toward America's infrastructure and industrial base, and not just pick a fight with one particularly ferocious competitor.

Meanwhile, if the trade deficit itself is to be blamed for the declining fortunes in the American heartland, neither the trade war nor its resolution had any meaningful effect. America's trade with China has come closer to balance as the volume of trade has dropped, and it might improve further if China meets its purchasing commitments under the agreement. But America's overall trade deficit has expanded even as the bilateral deficit with China has shrunk, because it is driven by macroeconomic factors, not the nature of agreements between particular countries. If America's persistently high trade deficit is a problem, we can only address it by increasing the savings rate (and, quite possibly, reconsidering the dollar's role as the global reserve currency, which could have other very negative consequences for America).

As with the renegotiation of NAFTA, the deal with China is likely to have more significance as a political matter than an economic one. By attacking NAFTA and China, Trump gained enormous credibility with Americans who had been hurt by the disruptions of the past 20 years, and who had been told by both parties that they simply had to adapt as the price of progress. Trump went to war for them, and now he's bringing home victories that, however small, may make them forget the casualties they suffered in the war itself.

Want more essential commentary and analysis like this delivered straight to your inbox? Sign up for The Week's "Today's best articles" newsletter here.

Noah Millman is a screenwriter and filmmaker, a political columnist and a critic. From 2012 through 2017 he was a senior editor and featured blogger at The American Conservative. His work has also appeared in The New York Times Book Review, Politico, USA Today, The New Republic, The Weekly Standard, Foreign Policy, Modern Age, First Things, and the Jewish Review of Books, among other publications. Noah lives in Brooklyn with his wife and son.