America's lurch toward 'competitive authoritarianism'

Why Wisconsin Republicans were so desperate to hold an in-person election in the midst of a pandemic

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Why were Wisconsin Republicans so adamant about holding an in-person election in the middle of the worst pandemic in 100 years, even though demand for absentee ballots catastrophically overwhelmed the system and effectively disenfranchised tens of thousands of people?

Suppressing the vote to deliver wins to President Trump is standard-issue Republican politics at this point, so unremarkable that the president himself admits its dark logic almost casually. But Last Tuesday's election for the court seat of Republican-appointed judge Daniel Kelly wasn't just important on its own terms. Rather, it was about locking in Republican power statewide for another decade, no matter what the electorate wants.

Preserving their hold on the state Supreme Court will let the GOP purge hundreds of thousands of voters before the 2020 elections and then do an end run around Democratic Governor Tony Evers in the post-2020 redistricting process. It's a clear-as-day example of the Republican Party’s lurch toward unapologetic authoritarianism. And even though Kelly lost the race to Democrat Jill Karofsky, narrowing conservatives' hold on the court from 5-2 to 4-3, the GOP's tactics are a terrifying harbinger of things to come for America.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Why exactly does a state Supreme Court race hold so much significance?

Wisconsin's 2020 state legislative elections will already take place with the same absurdly gerrymandered maps that delivered hefty GOP majorities in the state house and state senate in 2018 despite decisive Democratic advantages in the aggregate vote totals. Democrats won 53 percent of the vote but just 36 percent of the seats across the two legislative chambers. Barring some total collapse of Republican popularity in the next six months, there is almost no question that the Wisconsin legislature will remain in GOP hands.

But there remains the problem of Evers, the soft-spoken Democrat who narrowly unseated Republican Scott Walker in 2018. Like many, though not all states, Wisconsin's redistricting process (which redraws the boundaries of state legislative and national House districts) requires agreement between the legislature and the governor, and you would think that Evers gives Democrats a much better chance at negotiating something approximating fair maps for future election cycles. Wisconsin Republicans, therefore, might try to create the maps by using something called a joint resolution, which doesn't require the governor's signature.

While this is transparently illegal according to Wisconsin's own case law, and while state Republicans currently deny they are considering this option, the current composition of the state Supreme Court would almost certainly uphold the maneuver, granting the GOP another decade of illegitimate control over both the state legislature and the national House delegation, which has had a 5-3 Republican edge for the past decade despite the state's roughly even overall partisan split.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

This is why voters in Milwaukee were forced to risk their lives and the lives of everyone they know to stand in lines reminiscent of Soviet bread queues to vote last Tuesday. State Republicans couldn't have cared less about the results of the very much already-over Democratic presidential primary. This was all about that court seat, a long game that Republicans have perfected and which Democrats are only starting to understand.

To understand what Republicans have done in Wisconsin, you must first understand the logic of façade democracy, what political scientists call "competitive authoritarianism" or "hybrid regimes." These are countries where real political parties compete with one another in elections whose outcome is either predetermined or subtly rigged, or where some entity other than elected representatives holds the real power. While the recent experience of Hungary, where Prime Minister Viktor Orbán used the coronavirus emergency to make himself a dictator, might be the first thing that leaps to everyone's mind, the structure Republicans have installed in Wisconsin actually looks like a slightly more democratic version of Iran's government.

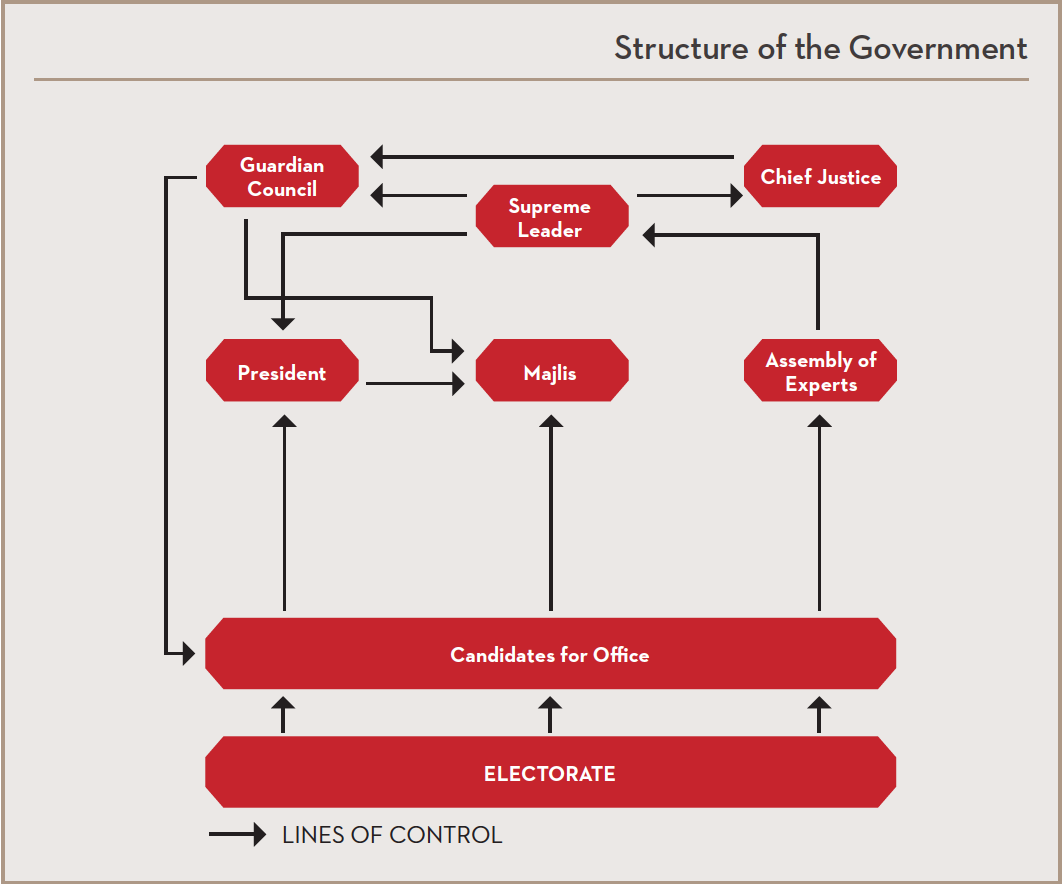

A unit on Iran is a staple of AP and university comparative politics classes, generally paired with some theory about the practice of authoritarianism. There are real elections in Iran, contested heatedly by different political factions. But the candidates are vetted first by unelected clerics, and often disqualified en masse as they were in the country's recent parliamentary elections (notably also held mid-pandemic). But while the elected parliament and the elected president cooperate to make laws in ways that often appear to be normal and democratic to the untrained eye, neither institution is vested with real decision-making authority.

The ultimate decider in Iran is the Supreme Leader, who is chosen by a body called the Assembly of Experts. While members of the Assembly are "elected," they must first be vetted by the Guardian Council, half of whose members are appointed by the Supreme Leader. The Guardian Council, in turn, can also challenge laws passed by parliament. When the Guardian Council and parliament cannot agree on a resolution, the dispute is mediated by another institution called the Expediency Council, whose members are chosen by — you guessed it — the Supreme Leader, who anyway has the right to bypass parliament and the president altogether and rule by decree.

I love to show students various renditions of a flow chart that depicts this pattern of circular, unaccountable power. It looks like this one, from Patrick O'Neil's textbook, Cases in Comparative Politics:

This kind of system is why political scientists rightly insist that democracy and authoritarianism are not either/or concepts but rather exist on a spectrum.

Obviously, there is no Supreme Leader in Wisconsin, and candidates for public office are not disqualified from running by an unelected body, or thrown in prison or executed. But Wisconsin has moved rapidly away from an ideal, well-functioning democracy toward a miserable and sclerotic form of competitive authoritarianism. And if state Republicans are able to get away with it, Wisconsin should be ranked closer to Iran than to Sweden or Germany on any index of political rights.

Think about the flow chart of power Republicans are trying to put into place. After Walker's loss in 2018, the outgoing state legislature conspired with him to strip the governor's office itself of various important powers, a classic authoritarian maneuver meant to kneecap your opponents rather than handing power over to them. By maintaining control of the state Supreme Court, Republicans have dramatically increased their chances of delivering the state to Trump in November and ensured their ability to gerrymander their way to indefinite power in the state legislature. Even if the state's electorate were to move 5 points toward Democrats, Republicans would likely still hold enough veto points in the system to block any changes.

Last week's unconscionable decision, upheld by the state Supreme Court, to force Wisconsinites to vote in person was itself a product of past authoritarian backsliding — imposing draconian Voter ID laws which disproportionately impact minorities, gutting public employee unions which were a huge part of Democratic turnout operations, rolling back early voting and more. In 2019, for example, Republicans won a different state Supreme Court seat by fewer than 6,000 votes, in a state where scholars estimate that 300,000 people lack the documents required by the state's racist voter ID laws.

That justice, of course, voted with the majority to override Evers' attempt to move the primary to June, gambling that massively reduced turnout in Milwaukee would keep a critical seat in GOP hands. And the U.S. Supreme Court's 5-4 decision to block an extension of voting by mail was itself issued by an illegitimate SCOTUS majority obtained in part by President Trump winning Wisconsin — which would likely not have happened absent Walker's Voter ID laws.

The whole set-up is an ouroboros, just like in Iran, with one authoritarian institution conspiring to protect the power of other authoritarian institutions — in this case, the Republican Party itself — from the few areas where voters actually get to weigh in. Similar efforts have been underway for years in states like North Carolina, and are already in place in states where Republicans are more dominant. In other words, millions of Americans already live under various forms of competitive authoritarianism at the state level, and if Wisconsin is any indication, many millions more will soon be condemned to that fate. The Republican Party's fear of the electorate, and its willingness to destroy democracy itself rather than alternating in power with Democrats, is now official policy, from Madison to Washington.

The only real question at this point is whether there is still time to stop the GOP from completing their installation of this rancid system across the entire country. The results in Wisconsin should give Democrats some hope that they can still overwhelm Republican voter suppression efforts with sheer courage, determination and persistence, but time is running out.

Want more essential commentary and analysis like this delivered straight to your inbox? Sign up for The Week's "Today's best articles" newsletter here.

David Faris is a professor of political science at Roosevelt University and the author of "It's Time to Fight Dirty: How Democrats Can Build a Lasting Majority in American Politics." He's a frequent contributor to Newsweek and Slate, and his work has appeared in The Washington Post, The New Republic and The Nation, among others.

-

The ‘ravenous’ demand for Cornish minerals

The ‘ravenous’ demand for Cornish mineralsUnder the Radar Growing need for critical minerals to power tech has intensified ‘appetite’ for lithium, which could be a ‘huge boon’ for local economy

-

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?IN THE SPOTLIGHT As the president muses about polling place deployments and a centralized electoral system aimed at one-party control, lawmakers are taking this administration at its word

-

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?Talking Point Peter Thiel and Larry Page preparing to change state residency

-

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one report

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one reportIN THE SPOTLIGHT By blocking an approved segment on a controversial prison holding US deportees in El Salvador, the editor-in-chief of CBS News has become the main story

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June

-

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardon

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardonTalking Point Convicted sex trafficker's testimony could shed new light on president's links to Jeffrey Epstein

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred