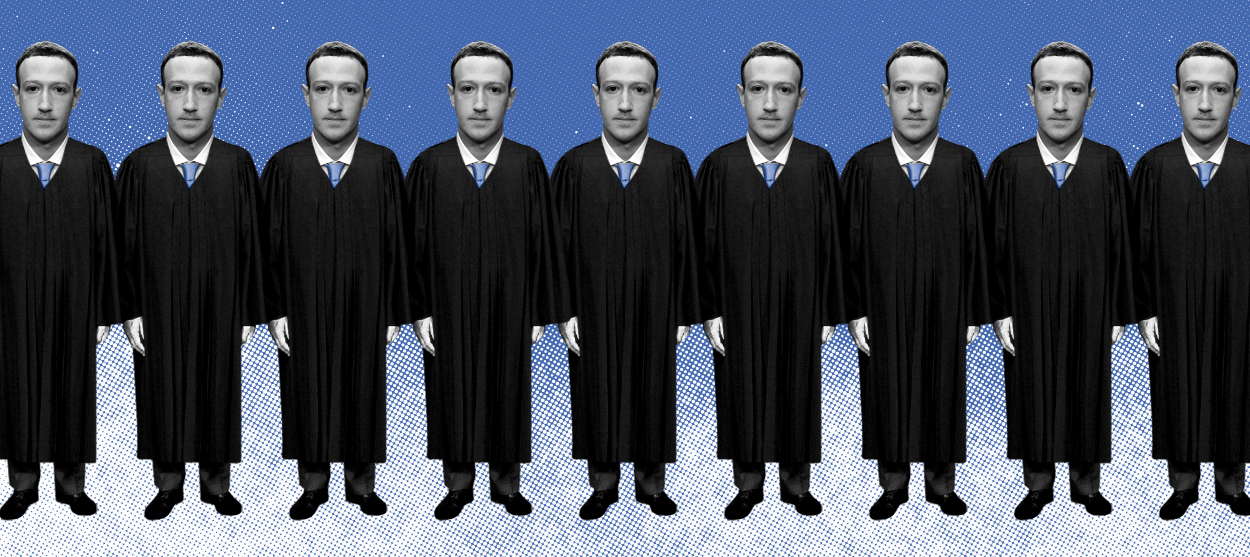

Facebook's 'Supreme Court' won't solve anything

They have been given an impossible task

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Sixteen years after its founding in Cambridge, Massachusetts, in 2004, Facebook is proud to announce that it has finally caught up to the technology standards of circa-1992 message boards. The social networking site has just announced that it has appointed a group of people who will be charged with reviewing "what content to take down or leave up." Congratulations, guys. You've re-invented the forum moderator.

Figuring out what if any real authority the company's self-described "independent oversight body" will have is difficult. A recent op-ed in The New York Times attributed to four of its members is full of windy phrases about "hate speech, harassment, and protecting people's safety and privacy" and the importance of being "independent, principled, and transparent." What this means in practice is anyone's guess, but if the authors are to be taken at their word, the oversight board will have authority over what content is published on Facebook and Instagram, authority that is "final and binding."

This seems to me unlikely. No company on the scale of Facebook is likely to allow any decisions to be made against the wisdom of its own legal counsel. The idea of the new oversight board as a kind of Supreme Court is misleading; the reality is more like the Independent Press Standards Organization in Britain, which largely exists to apply a gloss of impartiality to editorial decisions that newspapers and magazines would have made regardless.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

A more serious problem with the oversight board is that it elides the real question here, which is whether it is in fact possible for Facebook or similar websites to adjudicate meta-disputes about free expression in a way that is consistently "fair." The answer seems to me very obviously no.

"There is," as Stanley Fish memorably put it, "no such thing as free speech." The expression of facts, opinions, and ideas does not take place in some kind of free-floating empyrean but in the actual world of persons and societies, which are themselves the result of certain priorly defined commitments. In every society there will be certain principles or standards which are, for all practical purposes, beyond dispute and thus outside the realm of what we mean when we talk about free expression. Free speech is a second-order good, something that makes other, loftier ones, like health or the pursuit of virtue or racial equality, possible. It exists so that we can make art that ennobles us and brings us pleasure and so that we can debate questions like whether marginal tax rates ought to increase, not to facilitate earnest discussion of whether the Holocaust took place. Supposed speech that is by definition at odds with the actual first-order principles of a society is actually never tolerated, which is why no one believes that Holocaust deniers or proponents of flat-Earth theory deserve to have their views aired on CNN or in the pages major newspapers and magazines. (Increasingly it is common to find that web hosting companies deny their services to groups like Stormfront, which is the contemporary equivalent of having their printing presses seized.) This is also why we invent categories like "hate speech" to bracket off ideas that we think deserve neither protection nor consideration because they do not fall within the vast space reserved for prudential debate within our society.

It would be absurd to deny that the parameters of what is considered acceptable are constantly changing. As MSNBC's Joy Reid learned the hard way, jokes that were not only considered acceptable but amusing during the Bush administration would be considered hate speech by the same liberals who chuckled along with them on Air America in 2004. But the question of what is acceptable in a public forum extends far beyond the relative tastefulness of calling Harriet Miers a lesbian. There are serious considerations, many of them not abstract. There will always be edge cases, and there will always be someone to whom the hardly enviable task of deciding them falls.

This reality has become impossible to ignore during the current pandemic. It is worth pointing out here that if Facebook, Twitter, and other platforms had done what many journalists and experts had asked and banned any content that undermined the talking points of the World Health Organization and similar bodies, it would have been unacceptable to suggest that people should wear masks. (It would likewise now be unacceptable to question their efficacy.) The control of information during a public health crisis is a matter of serious importance. It is a good thing to give people access to information that is correct and bad to do the opposite. But who decides what is correct and what, if anything, is an acceptable means of expressing skepticism of official or quasi-official conclusions? And does it matter if the adjudicators are wrong? Is it better to err on the side of caution (about physical health or otherwise) or of license?

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

These questions are not new. They tend to be revived whenever there is a revolution in communications technology: movable type, daily newspapers, radio, cinema, television, the internet, and now social media. The inherent danger in making it easier for people to communicate is that it flattens our perception of reality. (This leveling effect was recognized by Kierkegaard, who wrote about it at some length in the 1840s.) Thanks to the internet, ideas that would never have reached beyond a small audience of newsletter readers have more cultural currency than the New York Times or PBS. Anyone using Facebook on a mobile phone has, at least potentially, a larger audience than even the most popular authors and periodicals of the last century, albeit with no editorial oversight or other limiting principles save the user's own inclinations.

All of which is to say that while I sympathize with Facebook's position, the creation of the new oversight board should be recognized for what it is: an abnegation. Faced with an impossible task, they have decided to pass it off to someone else. The new body should not be surprised if they find it as thankless as their predecessors.

Want more essential commentary and analysis like this delivered straight to your inbox? Sign up for The Week's "Today's best articles" newsletter here.

Matthew Walther is a national correspondent at The Week. His work has also appeared in First Things, The Spectator of London, The Catholic Herald, National Review, and other publications. He is currently writing a biography of the Rev. Montague Summers. He is also a Robert Novak Journalism Fellow.