A eulogy for 100,000 Americans

How do we memorialize the lives lost to coronavirus?

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

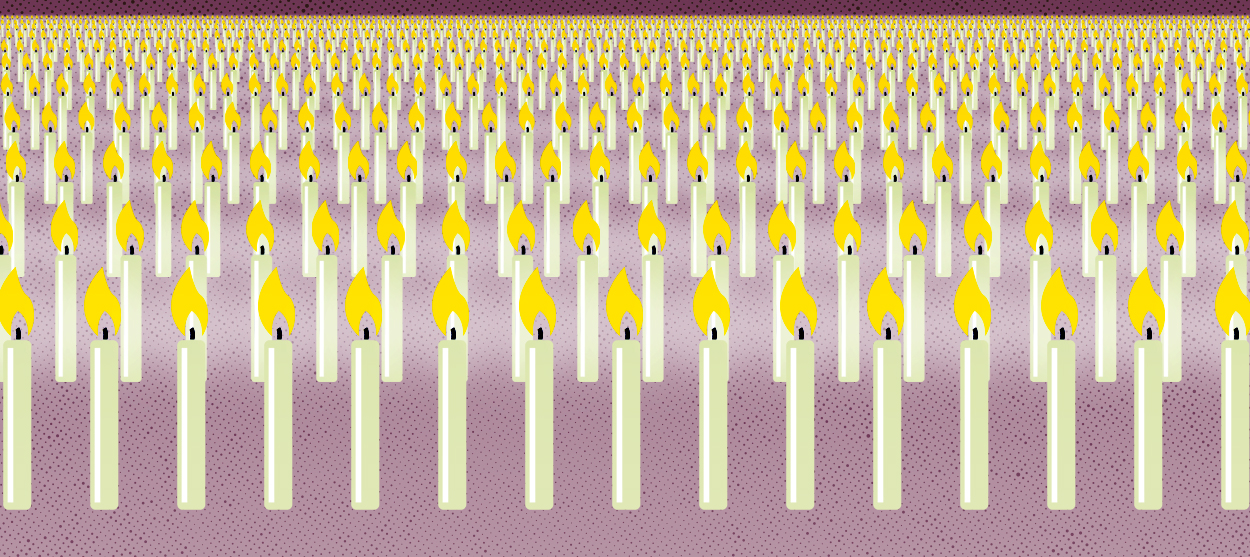

Imagine if, starting now, we held a moment of silence for every American who has died from COVID-19. We wouldn't speak for the rest of the day. For the rest of the week. For the rest of the month. If each one of those deaths was honored with the full traditional 60 seconds of silence, this country would stand in hushed, somber, unrelenting remembrance for just short of 70 days.

Sometime in the next few days we will officially record this country's 100,000th coronavirus victim. In truth, we probably passed that number awhile ago; the U.S. death counts are almost certainly too conservative. Still, that number is unthinkable. It means that in four months, more Americans have died from the novel coronavirus than died during the two decades of the Vietnam War. In less than 110 days, almost two and a half times as many Americans will have died than perished in car accidents in the whole of 2019, and over six times as many as the worst recent flu season.

But numbers, comparisons — these are just ways of trying to quantify something that cannot be measured: a life. "One hundred thousand" doesn't tell you about the 51-year-old mother, whose children, when they were young, would race down the stairs to help her with her bags. They don't tell you about the 59-year-old grandfather whose wife met him at a Harley-Davidson dealership and who, after his death, donated important images of his lungs to help fight the virus. They don't tell you about the beloved 67-year-old teacher who was mourning her 42-year-old son, who had died from COVID-19 in April, when she caught the disease herself.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

By now, you might even know someone who has died; one in eight Americans do. I am still one of the lucky; none of my close loved ones have become victims of the disease. There is an implicit and terrible addendum to that statement: yet. That possibility, that word, lives in a knot in my stomach like a parasite, a heavy, angry, terrifying thing gnawing away at me even when I'm not consciously thinking about it. But for now, my mourning is general and abstract, the numb sadness of a citizen. I hurt for my suffering country.

Yet America at large has not been permitted to grieve. At the most basic level, this is to keep us safe; funerals are heartbreakingly difficult to hold when gatherings are so dangerous, and there can be no moment of silence before a baseball game if there are no baseball games to begin with. It also seems misguided to hold a memorial when we're still in the thick of the tragedy. It would be a denial of the truth, that hundreds of people are still dying every single day.

At the same time, this leaves our grief unmoored. There is no ceremony to it, no ritual. We experience the stages of emotion at unsanctioned moments: sometimes I feel pity for those who refuse to listen to public health directives, sympathetic to the fact that denial is simpler, and sometimes I feel an explosive rage toward complete strangers that takes me hours to cool down from. Our mourning is directionless in this way, since we have not reckoned with our American tragedy collectively. We do not have a national memorial, there is no reading of the names of victims from the White House podium, though this weekend flags will finally be flown at half mast.

What scares me the most, though, is that we cross the threshold of 100,000 largely without a sense of catastrophe. It has been weeks since I organically stumbled into a daily death count on a front page or headline; it took me several attempts while I was writing this before I could find a website that showed how many people had died in the country in the last week. I share Teju Cole's longing "to be directly confronted with the fact, the enormity, the irreducible sadness of all these deaths."

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Instead, we mete out sadness with sickening calculations, and our leaders search for ways to minimize the tragic results of mismanagement, governmental neglect and a largely preventable crisis.

Does 100,000 not strike us with horror because of our contempt for the elderly and the unhealthy, our opinion that they somehow "deserve it," and our misconception that they are the only ones who are dying? Is it because the victims are disproportionately racial minorities that fail to drum up our sympathy? Is it because tragedy has not reached out and brushed us personally yet and we, in this country, are stunted in our ability to care about the suffering of strangers?

I'm thinking again of that impossible vigil for the 100,000 dead Americans. I'm thinking about how — after we'd counted out our 1,666th hour of silence, sometime in early August — thousands more people will have died since we started our endeavor. I'm thinking about how, across the country, we would work out the kinks in our creaky jaws, murmur to each other with our croaky, unused voices. And then, after a brief pause to collect ourselves, we would have to immediately begin our moment of silence anew.

Want more essential commentary and analysis like this delivered straight to your inbox? Sign up for The Week's "Today's best articles" newsletter here.

Jeva Lange was the executive editor at TheWeek.com. She formerly served as The Week's deputy editor and culture critic. She is also a contributor to Screen Slate, and her writing has appeared in The New York Daily News, The Awl, Vice, and Gothamist, among other publications. Jeva lives in New York City. Follow her on Twitter.